Over a third of Texans are fully vaccinated against COVID-19, and 42% have received at least one dose. In Harris County, 33% of all residents are now vaccinated — 40% of those who are 12 and older. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said the fully vaccinated no longer need to wear a mask indoors or out, with some exceptions. Efforts to distribute the vaccine in the U.S. have been consequential but they’ve stalled with a long way still to go. Access to vaccination sites is a problem for some in the U.S., for others its vaccine hesitancy or resistance. In combination, the unvaccinated, new, more transmissible variants of the virus and the rapid reopening of the nation's economy have many infectious disease experts conceding that herd immunity is likely out of reach. However, some scientists say Americans have been fixating too much on that as the pandemic finish line. Regardless, experts maintain the bottom line remains getting the vaccine into as many arms as possible.

But it's the "rapidly reopening economy" part of that equation, driven in no small part by those who didn't hesitate to get the vaccine, that's fueling the surging demand for goods and services, everything from used cars and laptops to milk, cereal and toilet paper. Rising demand, trailed by supply shortages, has led to price increases. In April, the consumer price index showed gains in every category and jumped 0.8%, according to the latest Labor Department report. In the past 12 months, the price of household and consumer goods has gone up 4.2% — the highest rise in inflation since 2008, when prices rose 4.9%.

In the Houston metropolitan area, consumer prices — the rate of inflation — increased 4.5% in April compared to a year before, and 1.8% since February of this year. Excluding food and energy, the index for all items increased 2.8% in the Houston area over the year, with notable hikes in the price of things related to owning a car. Energy prices jumped 32.9% in the past year, and auto insurance has gone up 11.9%. (It went up 9.5% between February and April alone.)

The higher price of necessities like toilet paper, gasoline and car insurance — the latter two, in effect, are necessities for many in the Houston area — will be felt most sharply by low-income Americans, a group that has been dealt a steady stream of hard hits since the pandemic began.

Everyone remembers the run on essential items like cleaning supplies, rubbing alcohol, paper towels and toilet paper in the early months of the pandemic when store shelves (both real-life and virtual) were empty. While there were cases of price gouging, in general, prices remained stable. So, what's the difference between the shortages then and now?

“When the pandemic first struck, paper, toilet paper was like gold,” Greg Portell at the consulting firm Kearney explained to the New York Times. “The optics of trying to take a price increase during that time just weren’t going to be good.”

Now, however, with consumers — many of whom have more disposable income because they've been staying home and not traveling or eating out as much — spending more and the economy gaining traction, businesses and manufacturers are passing the increased costs they incur from suppliers down the line. And so, as COVID-19's threat fades, the threat of inflation has emerged.

Retail spending response to COVID-19

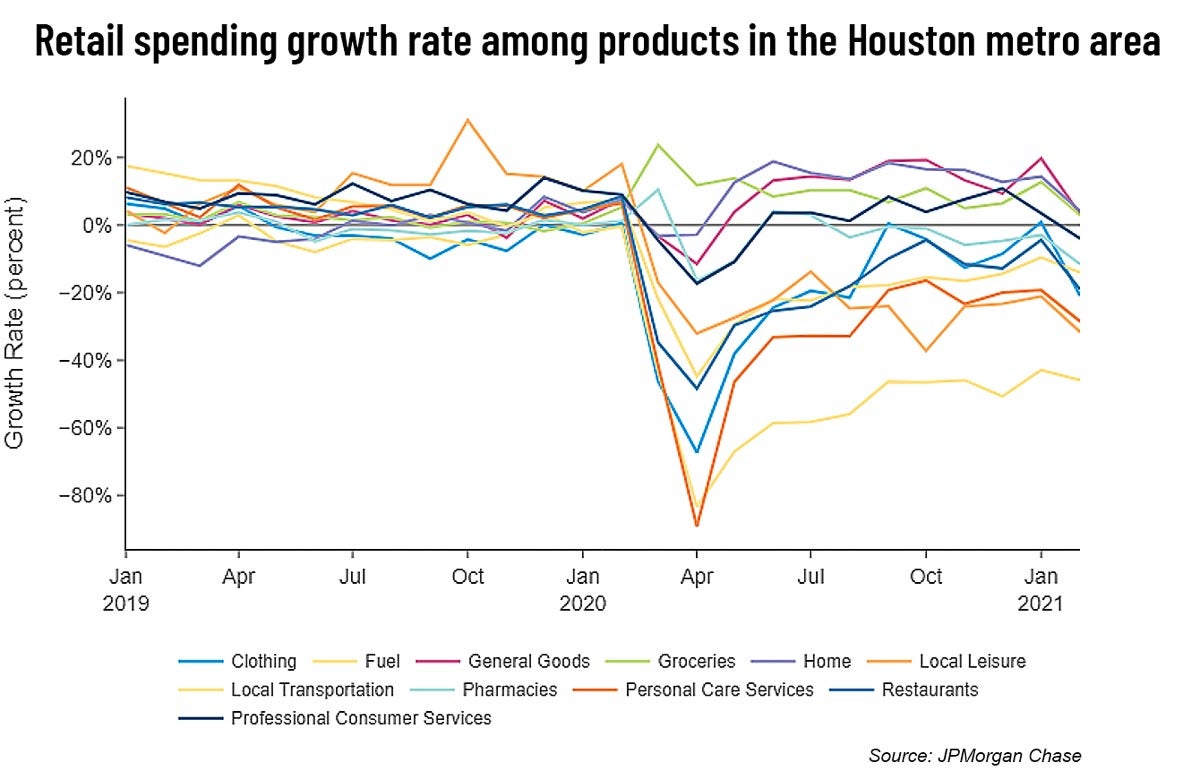

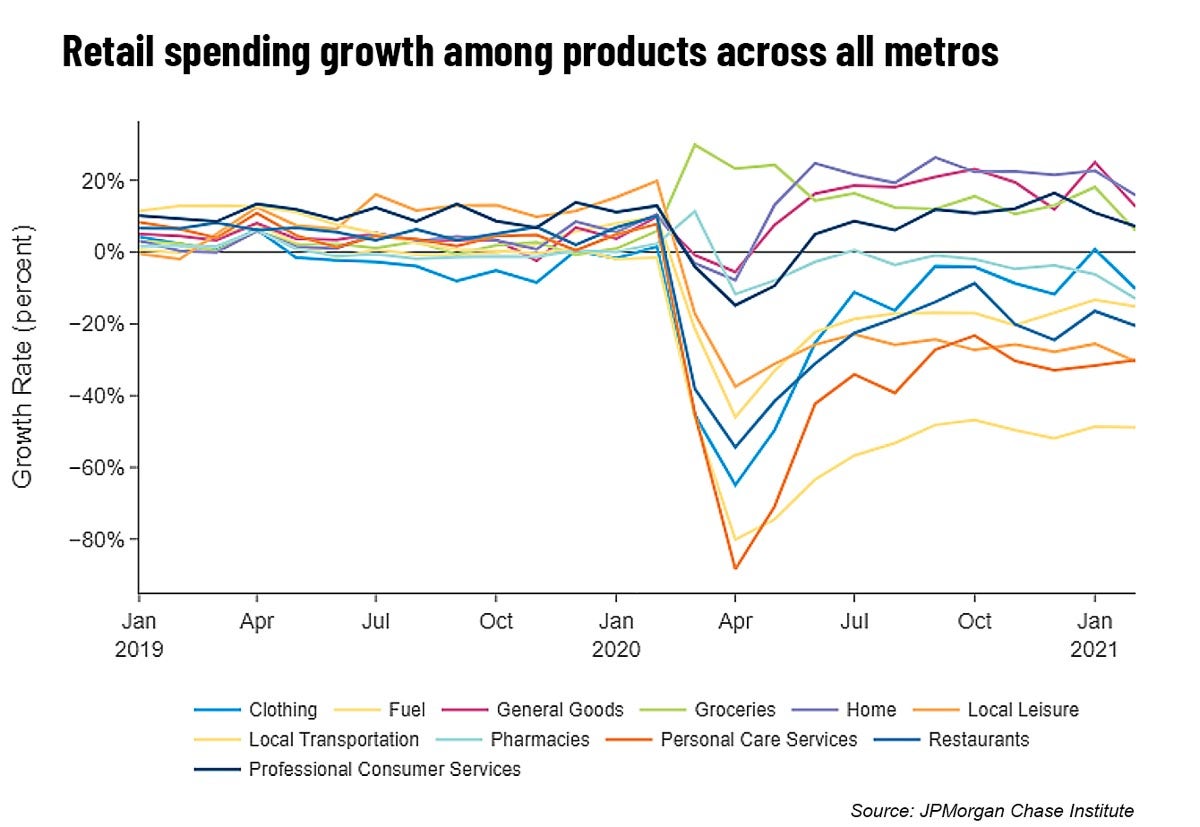

Spending — along with the economy — plunged sharply in March and April of last year on things like restaurants and bars, hotels, transportation and retail. The only exception has been spending on groceries, which jumped more than 20% when the nation shut down and has remained above pre-pandemic levels since then. In May 2020, consumer spending began to bounce back to varying degrees across all categories — even growing above 2019 levels for things like home goods (furniture, home improvement and landscaping services), general goods (department and discount stores, and big-box stores like Target and Walmart) and professional consumer services (child care, veterinarians and legal services)..

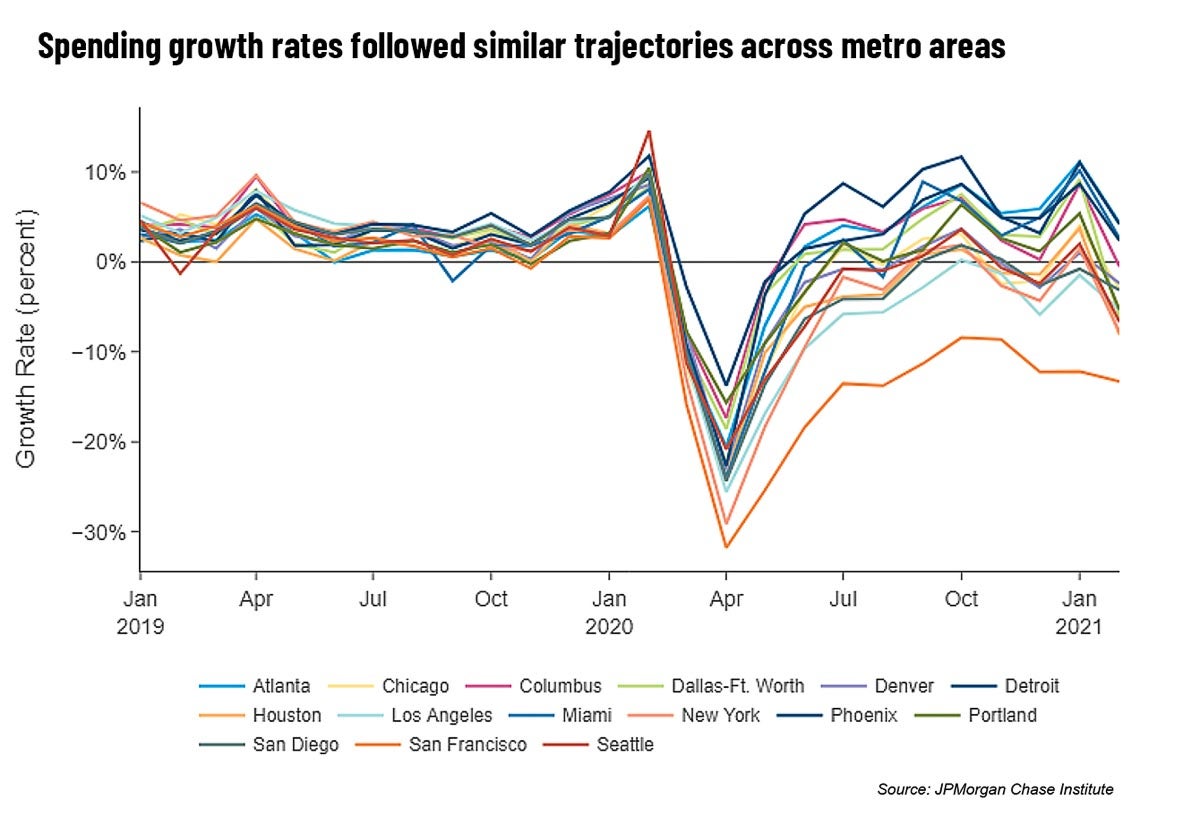

An analysis from the JPMorgan Chase Institute (JPMCI) of publicly available data on retail spending in 15 metro areas shows that, despite differences in COVID-19 death rates and restrictions imposed at the local level to slow the spread of the coronavirus, spending trajectories varied little across cities. In addition to Houston, retail spending growth was tracked for Atlanta, Chicago, Columbus, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, New Orleans, New York, Phoenix, Portland, San Diego, San Francisco and Seattle.

Chris Wheat, co-president of JPMCI, and his team used the transactions made by more than a sample of over 40 million "de-identified" credit and debit card users for purchases across 11 categories of products, everything from clothing, fuel and general goods to groceries, pharmacies and local transportation. Wheat and his team found "that the COVID death rate in a metro area in a given month was not a statistically significant predictor of spending growth." The weak link between spending and COVID-19 death rates at the local level, they say, has been shown in other research finding that disruptions to businesses in the Houston area and other metros weren't related to local infection rates.

Online spending continues to be robust

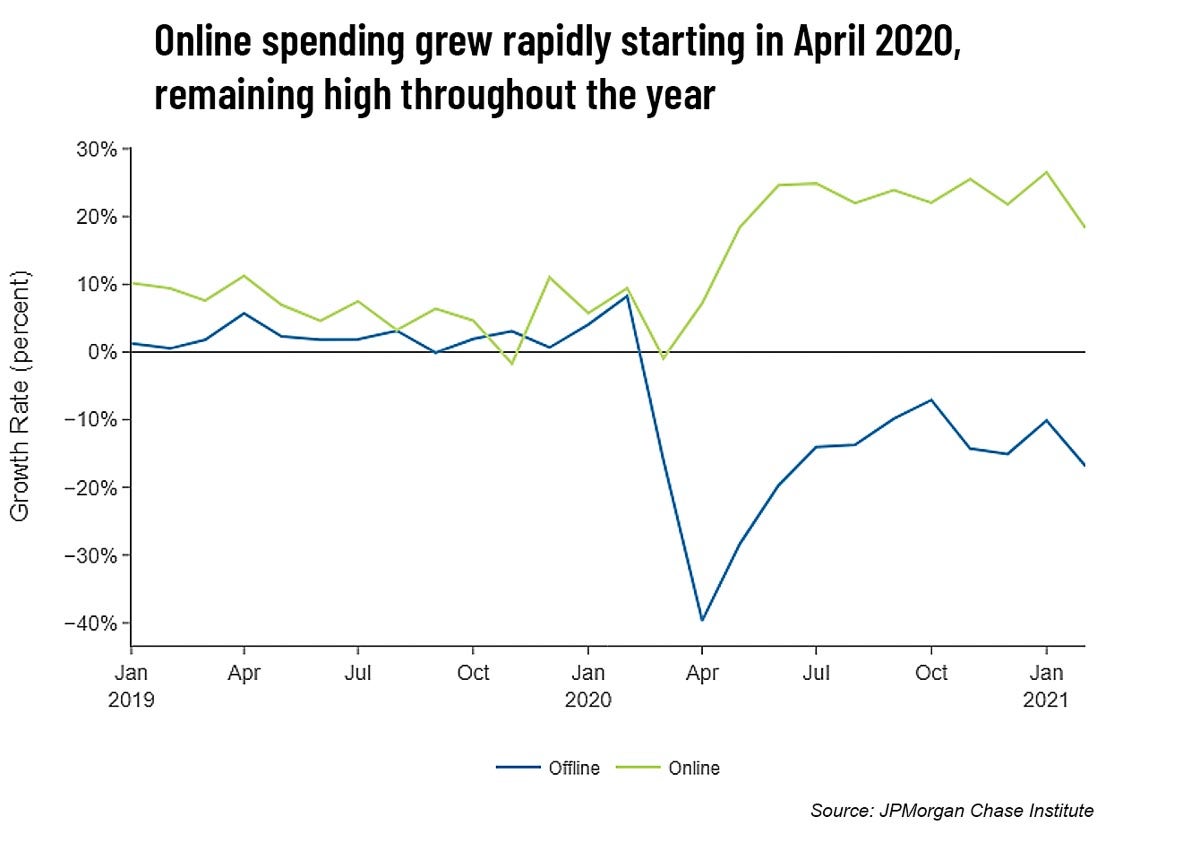

JPMCI's "Local Commerce Data Series" allowed the researchers to track purchases by channel: either online or in-person. Before March 2020, online and offline (in-person) spending was about the same. Not surprisingly, the analysis shows, the trajectories of online and offline spending growth went in opposite directions in March 2020. As of January of this year, the growth rate of online spending across all cities was 26.5% — nearly four times the growth that occurred a year before. At the same time, in-person spending shrank by 10%. In February, the most recent month the JPMCI data is available, online spending continued to grow, but at 18.3%, it hit its slowest rate of growth since April 2020. After the initial shock to the economy in April 2020, "offline" spending steadily recovered until November. The contraction in offline spending in the Houston metro area tracked closely with the nationwide declines in March and April of 2020, decreasing as much as 38% before beginning to recover.

The JPMCI researchers say it's worth noting that "one explanation for the smoother recovery of spending despite fears of infection is that consumers are increasingly taking advantage of online commerce."

Based on the data, Wheat said he couldn't predict if the trend in online spending would continue. It's possible, now that consumers have grown more accustomed to shopping online and have even bought items they wouldn't have before the pandemic—such as picking shoes without first trying them on or buying a house sight unseen—they'll change some of their spending habits permanently.

Some data suggests older Americans may not make online grocery shopping a lasting behavior change after the pandemic. Offline spending should also grow as more people are vaccinated and go back to spending money at salons, barbershops, arts venues, restaurants and movie theaters, as well as using public transit. In Houston and other metros, spending in those sectors shrunk the most during the pandemic and they've experienced the slowest recovery.

Spending recovered despite the pandemic’s increasing severity

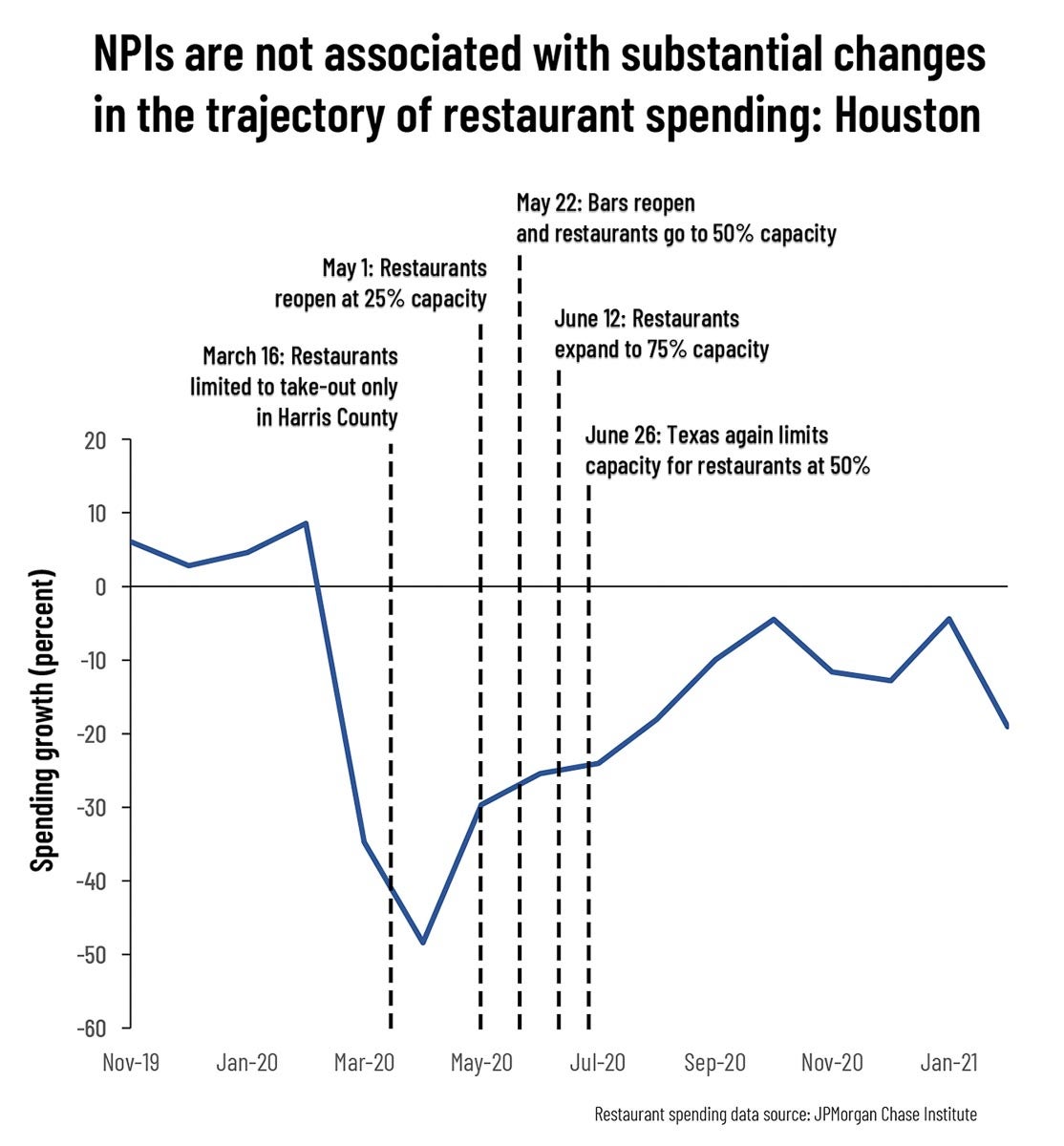

Another key takeaway in the JPMCI analysis was that data didn't show a strong link between changes in the trajectory of restaurant spending and nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), such as restrictions on restaurant service and capacity, and local COVID-19 death rates. Wheat and his team compared the Los Angeles and Seattle metro areas, which had "similar restaurant spending growth trajectories and very different COVID death rates," and found that the growth rate of consumer spending in restaurants wasn't affected by the severity of COVID-19 or the NPIs that were put in place in both cities to slow the spread of disease. Restaurant spending in both metros was over 50% lower in April 2020 compared to April 2019, but spending in restaurants in both cities rebounded between April and May and continued to improve through the summer and into the fall, even as both the COVID-19 death rates and the level of restrictions on dining that followed spikes in the two metro areas differed.

All 15 metro areas saw similar patterns in spending at restaurants: significant drops early in the pandemic, followed by steady growth through the summer before another decline in November. Wheat said it was unclear what caused the November drop that continued in December across the metros, possibly the colder weather in some cities impacted outdoor dining. In the Houston area, restaurant spending fell 48% in April 2020 but regained almost 19 percentage points from April to May. The upward trajectory continued through the summer, even as COVID-19 deaths in Harris County did the same. In November and December, spending declined (-11.6% and -12.8%, respectively) but improved in January when it was 4.4% lower than the year prior. However, it contracted significantly again in February when it was 19% lower than in 2020, according to the latest JPMCI data.

Overall, spending growth was negative across all 15 metros in February, shrinking 4.9%, after seeing positive growth of 2.7% in January. The contraction in spending was greater in Houston in February—8%. The metro saw spending grow 3.7% in the first month of the year.

The JPMCI researchers point out that, because these are year-over-year growth rates, they are sensitive to day-of-week effects, and February 2020 was a leap year. There was an extra day of spending, and that extra day was a Saturday, which, previous JPMCI research has shown, along with Friday are the days consumers tend to spend the most. Because of this, February 2021 spending growth can be "deflated by about one percentage point." One percentage point, however, doesn't do much to offset the decline in how much Houston-area residents spent at restaurants in February.

Beard and his team found that, while it's not obvious from the data that restrictions on restaurants constrained spending growth for restaurants, it's possible that inequalities may have impacted which businesses were able to more easily pivot and offer service that would keep them relevant in the pandemic's new reality. That included the ability to reach customers in new ways, whether that be transitioning a larger part of their business to online or being able to build an outdoor space for diners. However, as Wheat pointed out, "these investments require up-front and ongoing costs that not all business owners can afford."