For years, Americans have been willing and able to pack up their belongings and move elsewhere in the country in search of better economic opportunities.

But that period may be coming to a close, argues a new report by the Penn Institute for Urban Research released last month.

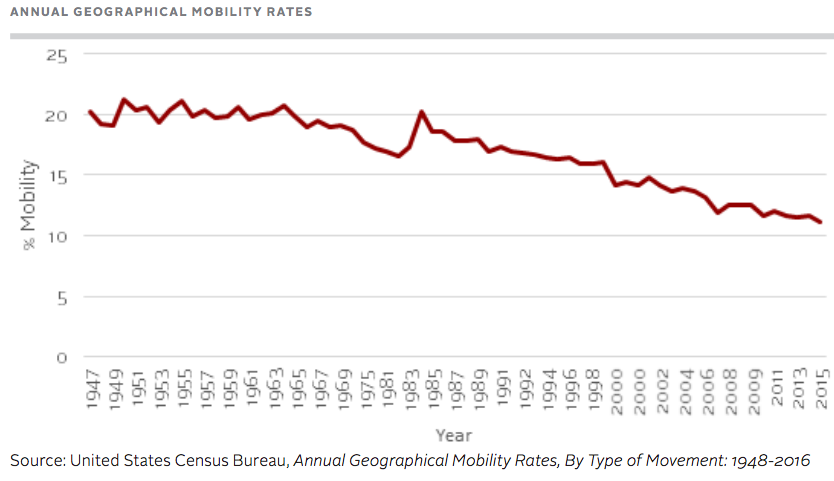

Average annual mobility in the U.S. -- the number of people who move over the course of each year -- is currently 11.6 percent. That's dramatically lower than the 19.7 percent average mobility rate from 1948 to 1980.

Article continues below graph.

That trend is significant enough on its own. But its importance is magnified when viewed in the context of the unequal distribution of job opportunities across the country.

New, high-productivity jobs are concentrated in expensive metros that have lots of amenities and attract high-skill workers. Meanwhile, lower-skill workers remain concentrated in areas with fewer opportunities. Even within metros, Penn researchers Arthur Acolin and Susan Wachter observe, a split is occurring as well: Central cities are booming, adding educated residents who live in pricey homes. Outer neighborhoods, meanwhile, are experiencing increased poverty. That's a trend that urbanist Richard Florida, for example, has been highlighting as of late. He calls it a "winner take all approach to urbanism that's failing."

At the same time, cities are seeing increasingly concentrated poverty. The number of people living in neighborhoods with poverty rates in excess of 40 percent increased by 72 percent from 2000 to 2010, according to Penn. The implications of this are significant. Research shows that when young people move to areas with lower poverty, their likelihood of attending college and having higher earnings increase. Yet it's harder to move.

So we have two simultaneous trends, which together the researchers call a "regime shift." The differences between cities (and communities within cities) are becoming more stark. Yet at the same time, it's becoming more difficult for people to move and access those areas that do facilitate more opportunities. That's in large part because the very places that have potential for job growth and the amenities that facilitate it, such as good education opportunities, are also prohibitively expensive for many people.

That hasn't always been the case, it should be noted. In the past, an increase in the supply of housing in growing regions has helped keep home prices accessible. But today, the regions with employment opportunities are also seeing home prices and rents soar, limiting the ability of people to access those communities -- and the jobs within them.

So what's the solution? In the long term, the researchers argue for a more comprehensive approach to economic development; increased education opportunities; and expanded job training programs.

“Skill-building programs and primary education reforms have the potential to increase access to opportunity for all households, enabling individuals born in low-income families to experience upward economic and social mobility," they write.

In the shorter term, there's evidence housing vouchers can help with mobility, the Penn researchers argue. But because vouchers are based on the average rent of an entire metro -- as opposed to a particular zip code -- they're structured in a way that limits access to the most desirable neighborhoods. The researchers say the system could be improved if granted more flexibility.

"Areas with higher income and housing cost growth in which fewer lower-skill workers are living are also those with a higher level of upward economic mobility for children born in lower-income families," they write. If those places become unattainable, they argue, the implications will last for years.

"A long term affordability driven increase in divergence in location by skill and income level would have implications for social inclusion."