Keerthi Bandi is a fourth year sociology major at Rice University. She is a research and communications specialist at Houston in Motion, where she collects background data and assists in the creation of materials to communicate results.

Yehuda Sharim is a Kinder Institute Scholar and postdoctoral fellow in Jewish Studies at Rice University. He is studying refugee communities in Houston through his project, Houston in Motion.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research or its staff.

Every once in a while, it happens: panic strikes the country. Momentary sensations trigger panic. As horror and tragedy dominate the screens, we hear the language of fear.

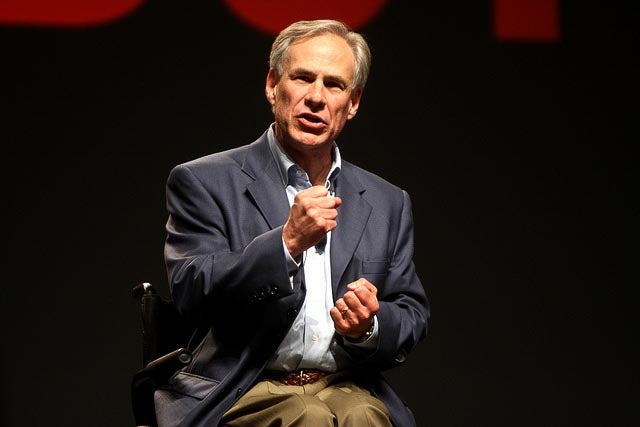

“I will not roll the dice and take the risk on allowing a few refugees in, simply to expose Texans to that danger,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said in a November news conference as he promised not to accept any of the 10,000 Syrian refugees the United States has pledged to resettle within its borders in the coming year.

Following the discovery of a fake Syrian passport near the dead body of one of the Paris attackers, Abbott joined 31 other governors across the nation in vowing to close off their states’ borders to Syrian refugees.

Logistically, preventing the refugees from relocating within the state’s borders is beyond the state’s purview. But another strategy for keeping Syrian refugees out is to limit the ability of resettlements to use the federal funds allocated to them.

The five refugee resettlement organizations based in Houston provide the most urgent and imminent services to the newly arrived refugees. They pick them up at the airport upon landing in Houston; help them open bank accounts; and guide stem as the search for employment. Those organizations already operate within a limited budget that enables only short-term support, often lasting no more than six-months.

In a recent letter sent to these organizations, state officials said that in addition to withholding federal funding for resettlement of new Syrian refugees, the state will also cease to fund services for already resettled Syrians. "If you have any active plans to resettle Syrian refugees in Texas, please discontinue those plans immediately," the letter said, according to KHOU. Failure to comply with the state’s demands, according to the letter, might result in cuts to funding vital to these organizations’ ability to provide services for refugees from other countries – not just Syria – who arrive in Texas. Indeed, Houston's refugees come here from places across the globe, including Afghanistan, Bhutan, Central America, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Myanmar, and Somalia, among other nations.

Amaanah Refugee Services is one of Houston’s non-profit organizations that provides services oriented towards refugees. It focuses on refugees who are Muslim but provides support to refugees regardless of faith. Ghulam Kehar, the nonprofit’s CEO, said some Houston refugee resettlement agencies understood Abbott’s letter as a demand for future compliance.

As a result, perhaps even in the coming weeks, some Syrian refugees — including those whom arrived just a few weeks ago — might be left without services and economic support crucial to their survival in Houston without forewarning.

As it stands, the six months of supplemental support that refugees receive after arriving in Houston is barely sufficient to learn how to navigate an entirely new environment, let alone secure stable living circumstances. Given that many of these refugees arrive to Houston with nothing, after decades of enduring the sub-human realities of life in refugee camps, it’s naïve to believe six months is enough time to create a stable life. The current debate only makes a stressful situation even more of a strain on these families, and consequently on the larger Houston community.

Houston regularly receives the largest number of refugees of any city in Texas and was designated to receive 100-150 Syrian families throughout the coming year. Abbott’s threats, however, jeopardize that possibility and leave many resettlement organizations in the impossible position of having to assess the relative worthiness of human life.

As a privately funded organization, Amaanah will likely do better off than the federally funded resettlement agencies a result of the increased donations that should follow in the wake of this controversy. Like other NGOs operating in Houston and targeting the growing refugee population, the organization’s independence from federal funding will likely put them in a better place to provide services to Syrian refugees than the resettlement agencies themselves. But groups like Amaanah alone aren’t enough to address the urgent needs of the displaced.

Still, despite the current environment of fear and isolationism, Kehar remains optimistic. “It’s not a part of our values as Americans,” he said. “The nation and the local communities’ values will overcome [this].”

On a recent Saturday, Houstonians gathered in support of Syrian refugees at the Galleria and echoed similar confidence in the resilience of American ideals. They urged state leaders to uphold their legal and moral responsibility to support refugees.

Janan Beck, a native of Syria who has been in Houston for the last four years and now volunteers to assist those displaced by the war said many of those who are recent arrivals have suffered great trauma. Their stories haven’t been highlighted in the governor’s discussion of refugees.

“The refugees want to work, they want to live, they want to be good citizens,” Beck said. “You can’t generalize based on a few hundred or thousand [people]. Just as the KKK doesn’t represent Christians, ISIS isn’t Muslims.”

Dr. Mohammad Abbas, a Syrian-Kurdish-American who was educated in Moscow (Political Science) and returned to Damascus only to flee political persecution, has been living in Houston for the last twenty years. He explained how the identity of Syrians has now become intertwined with terrorists. “It hurts that they treat and uniformly reject everyone as the same,” he said. Abbass and his wife Avin remain closely connected to the Syrian community in Houston. “Before we came here, we thought everyone cared,” his wife Avin said. “But now we see, they only care about things within their borders.”

Refugees seek new lives in places like the United States – and Houston – even if means starting over with nothing. And yet their struggle has become even more pronounced in light of an attack in which they played no role. “I feel like I was sleeping and now I’m waking up,” Avin said. “Where’s all the talk of freedom and humanity? Where did all of that go?”