Some housing units are affordable because they have been built with public subsidies, or their rents are assisted by housing agencies, often through federal funds. But the vast majority of affordable units in Harris County receive no subsidies. These units are called “naturally occurring affordable housing,” or NOAH, and they are more vulnerable to declining quality and increasing rents than subsidized units are.

Many of these properties were built several decades ago, and their rental prices reflect the age and quality of the buildings, which may have varying levels of improvements and maintenance over their lifetime. Other types of affordable housing on the private housing market may be less expensive because they are located far from bustling central business districts and trendy neighborhoods, with lower land costs. In either case, these units can become unaffordable when land values increase or when property owners invest in improvements and increase rents to recoup their costs.

Ideally, NOAH would be preserved in places that are near high-frequency transit serving job centers, and higher-quality units could be renovated at a lower cost than rebuilding lower-quality units. At the same time, attention to NOAH’s flood risk is also key. By looking at each of these factors, housing preservation advocates might be able to better target their efforts.

Location and proximity to transit

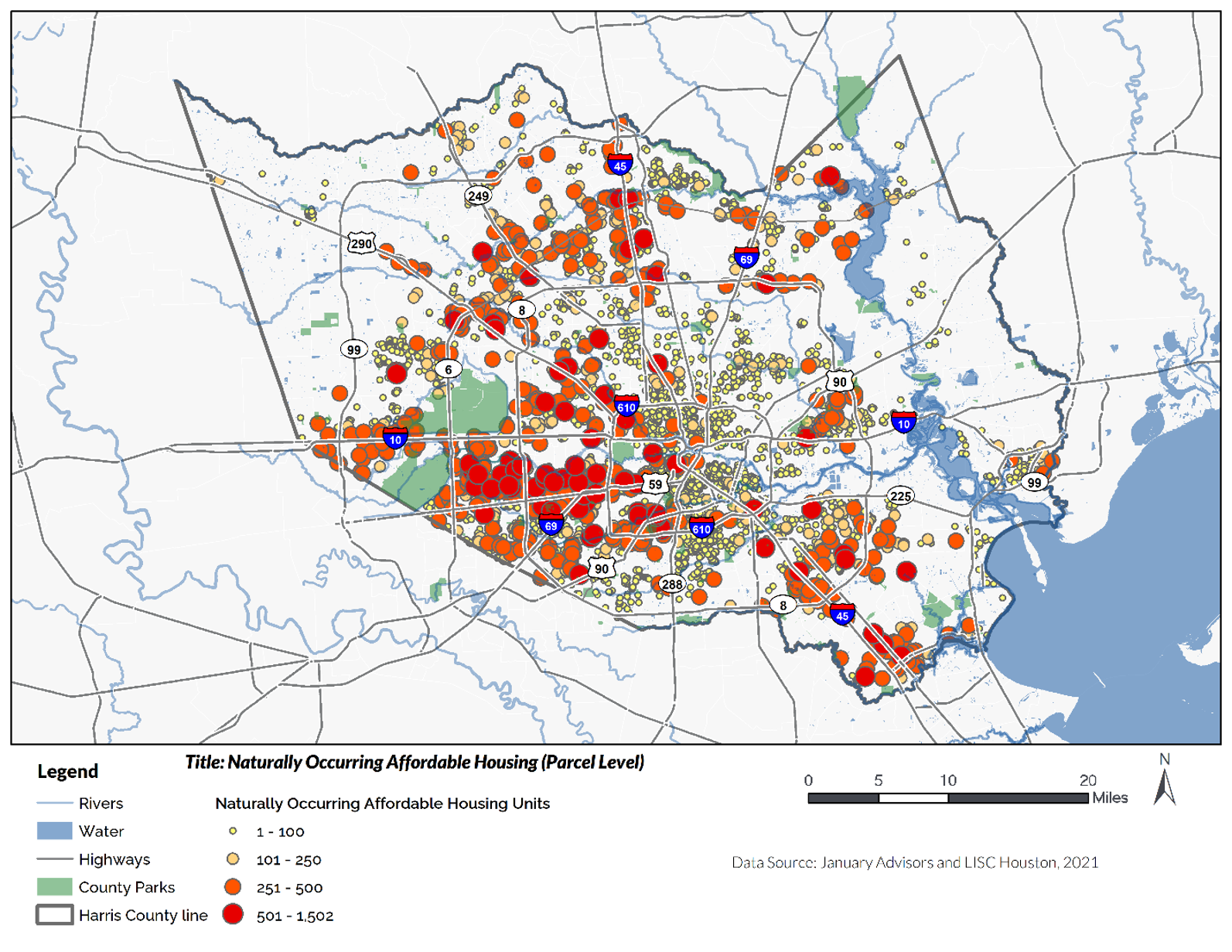

NOAH, which consists almost entirely of multifamily units, can be found throughout the city of Houston and Harris County. A majority are situated near major highways or arterial roads, particularly on the west side of the county.

One of Houston’s most noticeable NOAH corridors falls in southwest Harris County, where about 40% of the county’s 314,000 total NOAH units can be found. This southwest corridor is concentrated alongside Westheimer Road, Richmond Avenue, Westpark Tollway, and Highway 69, where large swaths of multifamily properties were built between 1960 and 2008. This area is also located between single-family dominant small cities— Hunters Creek Village to its north and Bellaire to the south — and residents in this corridor have easy access to jobs throughout downtown, the Galleria area and further west.

All in all, the distribution of NOAH in Harris County is different from that of federally assisted rental housing, which is fairly scattered, with some concentrations in northern, eastern, and southern Houston.

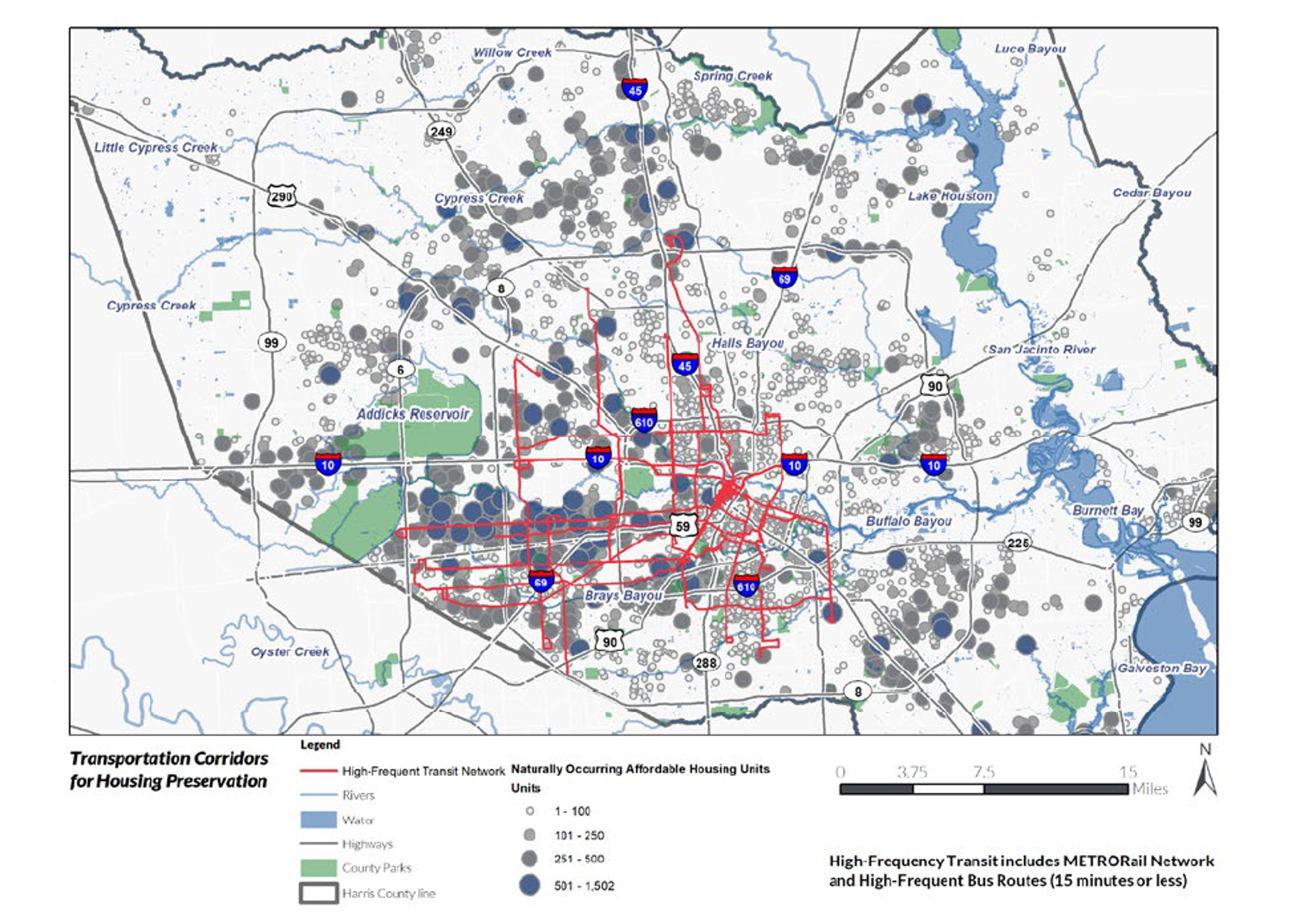

Another dimension to consider is the proximity to transit. Some low-income households, including those who live in NOAH, are more likely to use public transit to complete regular daily or weekly trips (e.g., jobs, schools, grocery stores, etc.) It makes sense, then, to prioritize NOAH preservation along high-frequency transit corridors.

While a number of high-frequency network connections are available for NOAH residents in the southwest area, their main options are bus routes along Westheimer and Richmond. Metro’s three light rail lines are Downtown and Med Center-focused, connecting to neighborhoods in the north, east, and southeast areas of the city, where federally assisted affordable housing units are primarily situated. Residents on the west side do have access to the new MetroRapid Silver Line along the western edge of I-610, the first leg of a forthcoming bus-rapid transit network connecting the west side of the county to the Galleria area and downtown.

Local governments and non-profit organizations should prioritize NOAH units close to current and planned high-frequency transit corridors. The My Home is Here affordable housing initiative with Harris County’s Community Services Department report, for example, advocates for better alignment of high-frequency transit and affordable housing. Given the role that transportation costs play in the Houston area, it is imperative to prioritize areas overlapping high-frequency bus services and sufficient existing NOAH units, as suggested in Kinder and LINK Houston’s 2020 report.

Quality of NOAH structures

The Harris County Appraisal District (HCAD) rates the physical building quality of most NOAH units as neither “superior/excellent” nor “low/very low/poor.” Instead, most units were rated either “good” or “average” quality in 2019, based upon the HCAD’s quality definition. The “average” grade represents normal wear and tear. This score also does not take into account the condition of the interior of the building, its plumbing and HVAC systems, and other factors.

Although a majority of average-quality NOAH units may not require substantial renovation, they certainly need more upkeep than a newer apartment building. Delayed maintenance only accelerates the deterioration of NOAH properties and increases the cost to repair in the future.

Much more data is needed about NOAH structures beyond the county’s assessment. The uncertainty about maintenance needs does lead to a serious concern about housing preservation efforts. About 180,000 NOAH units may be in danger of reaching a point that physical conditions would need substantial repair. It is difficult to estimate how many of them will simply be demolished, but one estimate based on previous Kinder Institute research shows about 42,000 NOAH units are located in census tracts susceptible to future gentrification (defined as having a 50% or higher susceptibility index). This number is equivalent to about 13% of the total NOAH stock.

As it was emphasized in our report, non-profit efforts in preserving the affordability of NOAH in Harris County are pivotal. For example, Avenue CDC uses public funds to acquire housing at risk of losing affordability and keep its rent level while making significant improvements to the building.

NOAH and flood plains

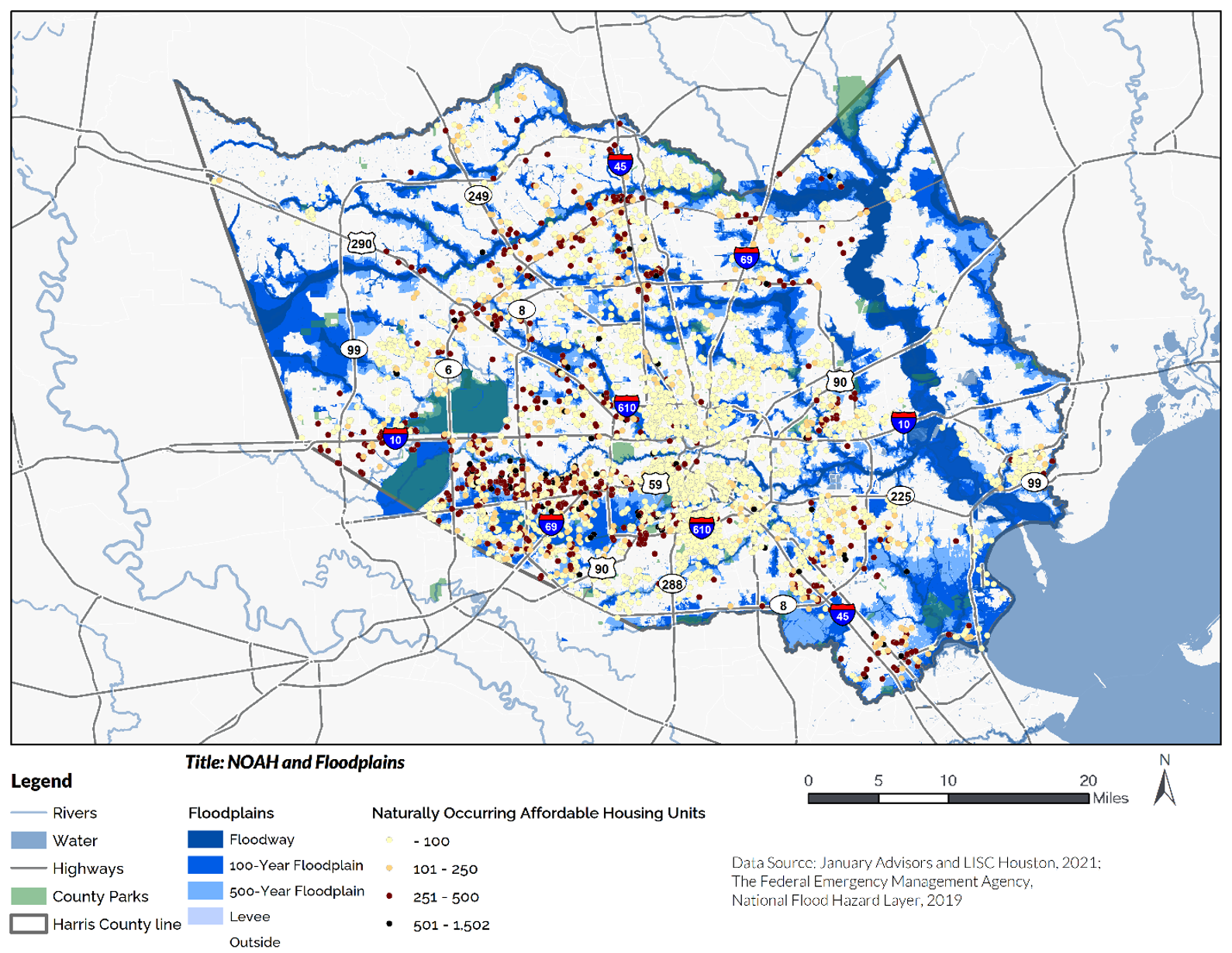

Based on the analysis of NOAH units and flood plains from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), about 10% of all NOAH units are situated within the 100-year flood plain, and several properties are in the floodway.

When adding the 500-year floodplains to this number, approximately 24% of the total NOAH units are within areas having greater than a 0.2% annual chance of flooding in any given year, a number is based on probability, not the history that we have seen in the Houston area.

A significant portion of the southwest NOAH cluster above Westpark Tollway is located outside designated floodplains, while some units near Brays Bayou are at higher risk of flooding. As the Greater Houston Flood Mitigation Consortium points out, a large number of NOAH properties near Greens Bayou on the northwest side face higher risks as well.

Clearly, any property in the floodway should be removed, which the city of Houston has set as a goal to accomplish by 2030. Some NOAH units would be lost in the process, so special care must be taken to relocate these residents to equally affordable housing, either in NOAH or publicly assisted housing, prior to demolition.

Moreover, NOAH units in the flood plains are subject to the city and county’s development guidelines requiring much higher base flood elevations, a requirement that is triggered by building permits for significant improvements. This means significant redevelopment of these NOAH sites could face higher costs for elevating and retrofitting these properties to be more flood-resilient. This could make them less desirable for preservation from a cost-benefit perspective unless subsidies can be offered. This also means some NOAH apartment buildings in the flood plains could, in theory, be maintained for decades without triggering the elevation requirements. But this is not ideal, as these residents, particularly on the ground floor, will face increased flood risks and deteriorating building conditions.

All other things being equal—if the county had two NOAH properties of the same quality, same size and same proximity to transit—it would be less costly to maintain a NOAH property outside a flood risk area. To that end, financial and administrative incentives (e.g., tax incentives, reduced parking requirements, expedited permit processing, etc.) should be encouraged for qualifying affordable housing development projects outside the flood plains, while other measures, such as green infrastructure and flood resilience projects, could help protect NOAH that remains in the flood plains.

Looking at these factors, it’s clear that a comprehensive strategy to preserve affordable housing will require a data-driven approach, including the creation of new datasets on building conditions and guidelines for inspections.