In November 1979, Houston City Council went from being almost exclusively male and white to being dramatically more diverse, literally overnight, as voters elected the council’s first two women and its first Mexican-American, and tripled the representation of African-Americans. The new council was also on average 10 years younger. It was a new day in city politics—thanks to federally required reforms that led to single-member districting—and Houston never looked back.

This is the first in a two-part look at Hispanic representation in municipal politics. Part 2 explores the experiences of Hispanic candidates in two other strong-mayor, progressive cities.

The current council, elected in 2019, broke new ground as the first to have a female majority— nine women and seven men—another laudable achievement. But the election also resulted in an unbalanced racial and ethnic profile: nine White, six Black, and one Hispanic. If proportional ethnic representation were the goal, the makeup would be closer to four White, four Black, seven Hispanic and one Asian.

“It's mind-boggling to see such a large population be so grossly underrepresented,” said Andy Canales, executive director of Latinos for Education and chair of the Texas Latino PAC, which campaigns for increased Latino elected representation in the Houston area.

As legal challenges confront Texas’ redistricting over failing to account for Hispanic voters, and as Harris County redraws its own precinct maps, it seems opportune for Houston to reflect on how effective its own boundaries are for delivering balanced representation—in particular by looking at a district created 10 years ago to do just that.

Whose opportunity?

Houston is home to 1 million people who identify as Hispanic/Latino (going by the Census definition), accounting for 45% of all residents.

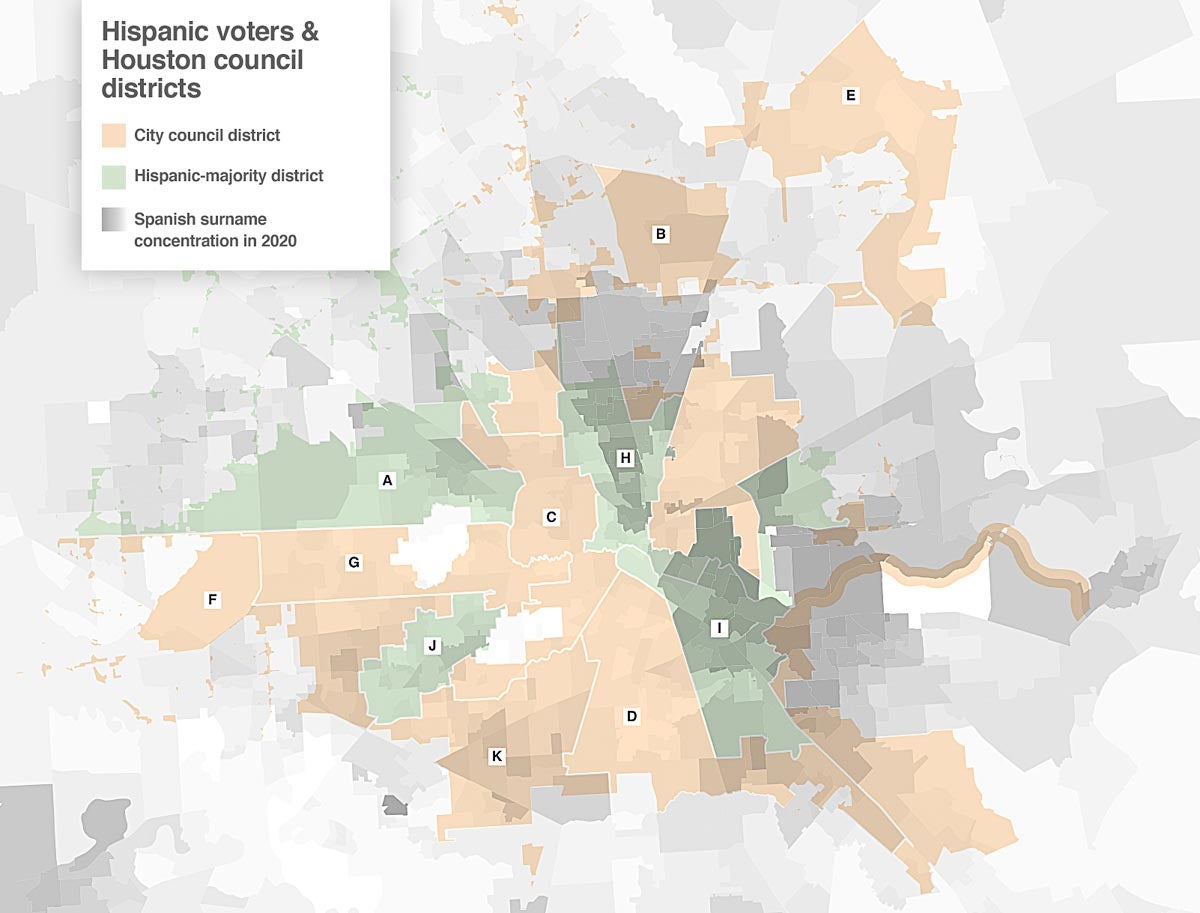

Four out of the 11 city council districts in Houston have Hispanic majorities in terms of total population—one of which, District J, was created in 2011 ostensibly as an “opportunity district” in Southwest Houston. The new district came about after extensive public involvement and the endorsement of a significant Hispanic coalition, including business leaders and community groups.

“If the Latino community gets behind the right candidate, funds that candidate, assists that candidate in mobilizing voters … there’s no question in my mind that this district can elect a strong Latino leader to city council. … But it’s not going to happen automatically,” Mayor Annise Parker said at the time.

In fact, it has never happened.

There is indeed a significant Hispanic population in District J—almost 120,000 people, almost two-thirds of the total.

However, when District J was created, Hispanics accounted for only 17% of registered voters there, based on Spanish surname estimates. And after a decade of city, state and national campaigns, however, known Hispanic voters comprised about 16% of registered voters in 2020, according to figures provided to the Urban Edge. In other words, Hispanic voting participation is virtually unchanged, relative to other groups.

Robert Jara, who was part of a group in 2011 that advocated for creating a Southwest Houston district combining the Gulfton and Sharpstown neighborhoods, downplayed District J as a Hispanic stronghold.

“It was more of a strategy to put together neighborhoods in such a way that they get more attention, especially when it comes to city services,” Jara said. “It wasn’t going to be a Hispanic-led district overnight.”

Of the 13 candidates who ran for District J since 2011, six came from the Hispanic community. They have included relatively experienced insiders who worked for city council members as well as wide-eyed political newcomers. Some have had key endorsements from unions and Hispanic groups, but few have been competitive.

The two people who have been elected to District J seem to have had one factor in their favor: previous campaign experience—and the fundraising chops, organizing skills and name recognition that comes with that.

Mike Laster, who is White, was elected in 2011, 2013 and 2015 (when term limits were changed to two, four-year terms instead of three two-year terms). Laster secured a final four-year term in 2015 after a runoff against a White conservative candidate. Before all of that, he had mounted campaigns for District F (before redistricting) and had made a bid for a state house seat.

Attorney Edward Pollard, who is Black, was able to replicate Laster’s success in 2019 after his own failed state house candidacy, though he did have to face a runoff against Sandra Rodriguez, who up to that point had been the most successful Hispanic candidate in District J.

Getting the vote out

Obviously, Hispanic voters should support whomever they like, regardless of ethnic identity. After all, opportunity districts cannot guarantee a specific kind of ethnic representation in elected bodies; but they are meant to ensure minority voters are not overhwelmed by design.

While perhaps not overwhelmed by design, Hispanic voters are certainly overwhelmed in effect. In 2011, Hispanic voters were outnumbered 2 to 1 by White voters, despite there being two Hispanic candidates that year. In 2019, there were almost 2.5 times more White voters than Hispanic, despite there being multiple Hispanic candidates. On top of that, 50% more Black people voted than Hispanics that year in the district as well.

These differences are critical in a low-turnout district like J. In fact, the district had the second-worst voter turnout of all districts in 2019, with less than 15%. City elections broadly already suffer from lackluster turnout rates, with Houston's around 20% as the norm over the past decade.

That means it doesn’t take many votes to tilt the result in one candidate’s favor, but it is certainly true that a candidate can’t capture District J, or many other districts for that matter, without a broad multiethnic coalition.

This is particularly a challenge for District J, which is 84% renters, a group that is prone to move between election cycles. District J also has a large foreign-born population with varying citizenship status, and an estimated 74% of households do not speak English at home. That means voter outreach and education must be multilingual and culturally aware, for example, addressing the layers of distrust that some immigrant communities have regarding elections and government services.

What’s the untapped potential in District J? Take the citizen voting age population (CVAP) estimates produced by the Census Bureau. Across the state of Texas, for example, 75% of White people were considered citizens of voting age in 2019, while less than half of Hispanic residents were. Keep in mind, this is a factor of age as well as citizenship status.

District J has an estimated 80,000 voting-age Hispanic residents. If only a fourth of them were citizens (half the state average), that would still mean 20,000 potential voters. But in 2020, there were fewer than 9,000 registered.

“I hate hearing ‘Hispanics don’t vote.’ … They don't vote because no one has empowered them. No one has activated them. They're there, waiting for us,” said Diana Patino, a consultant who worked on Rodriguez’s campaign and helped form a PAC designed to target women who have never voted. “The numbers, the demographics are changing. ... But why wait? Why can’t we do it now?”

Reclaiming representation

District J is not a Hispanic opportunity district, though it is perhaps what one political consultant called an “opportunity-for-anyone district,” which is fair. Meanwhile, it’s possible that other Hispanic strongholds will weaken over time.

“The Hispanic population keeps growing, but it’s growing more diffuse,” said Jara, the consultant who advocated for District J’s creation. “I think it would be extremely difficult to draw a new district that is truly a Hispanic district. You’re seeing gentrification and rapidly changing neighborhoods in A, H and even I.”

He’s right about that. According to 2020 Census estimates, District A (which includes the Spring Branch area), District H (Northside) and District I (East End) all have slightly smaller majority shares of Hispanic population relative to other groups than they did in 2010, while the share of the Hispanic population is growing slightly in all other districts.

However, Jara says citywide races (at-large positions, mayor, controller) could become more attainable than some district races as the Hispanic population grows. This would be signficant if it does happen, as prior Kinder research has shown that Hispanic candidates have been less likely to win at-large races than district races.

Revising council district maps remains an option this year, but it’s unclear if that would be pursued or whether it would even be effective. The lesson of District J is a lesson in follow-through. Map lines can create pathways to city hall, but it falls on Hispanic candidates themselves, their supporters and the coalitions they build to bring about more representation.