This post is part of a series by the Kinder Institute for Urban Research addressing the findings of the 2021 State of Housing in Harris County and Houston report. Explore other posts in this series.

The 2021 State of Housing presents information on the local housing system right before COVID-19 hit. In that report, we mostly used data from 2019, which is the most recent year for which American Community Survey (ACS) data is available.

Those data suggest a reason for the racial/ethnic differences in who COVID-19 killed. To summarize: over half of Houston’s COVID-19 dead were Hispanic (51%, or 1,458 people as of June 23), despite being only 45% of the city’s population. The share of Black COVID-19 victims was slightly smaller than their population share (23% of the population, 21% of deaths), while Asian and white Houstononians were also underrepresented.

Early analysis of COVID-19 outbreaks linked urban density and the disease’s spread, largely because the worst early outbreak was in the densest metro center in the United States: New York City. On Manhattan’s sidewalks and subways, it is difficult to isolate oneself from one’s neighbors. Hence the virus freely floated around crowded public spaces. Yet as scientists built knowledge of COVID-19’s spread, they learned that one needed more than a quick on-the-sidewalk encounter with an infected person to catch the disease. One needed to spend extended periods of time indoors with someone harboring the virus.

These extended indoor interactions likely happen at home. A New York University Furman Center research project into that city’s COVID-19 spread found that it wasn’t necessarily population density but housing crowding that accelerated the virus’s contagion. (A Calmatters study of California from June 2020 found similar results in that state.) A crowded home means that if someone catches the disease, they cannot effectively quarantine from others in their household.

I should emphasize that despite being an island of attached and dense multifamily buildings, Manhattan actually has a lower percentage of overcrowded households than Harris County (5.6%, compared to 5.3% in Manhattan).

According to this year’s State of Housing, the overcrowding problem, caused by an increase in cost-burdened households, would have made it hard for a large share of Houstonians to quarantine. We had a growing overcrowding problem at precisely the wrong time.

In Harris County in 2019, right before COVID-19 hit, the amount of severely overcrowded renter households (having more than 1.5 residents per room) increased around 25% in only one year, reaching 23,256 households. This represents only 2% of the county’s households, yet a larger share of its population. When observing overcrowded households (more than one person per room), the number is around 6% for both the county and the city.

In 2019, Harris County renters earned about 60% of the median household income of homeowners, were 3 times more likely to live in overcrowded conditions and almost 5 times more likely to be severely overcrowded.

Examining data by race/ethnicity finds a similar divide: in Harris County, Hispanic-headed households are about 10 times more likely to be overcrowded than white non-Hispanic-headed households (10.9% vs. 1.2%). Black- and Asian-headed households are in the middle (4.3% and 4.9%, respectively). Hispanic Houstonians were also the ethnic/racial group with the most outsized death share from COVID-19.

To bring COVID-19 home, one must theoretically catch it outside of the home. This often happens at work.

Being able to follow the stay-at-home orders was a luxury for the wealthy. Extensive research from the U.S.’s 12 largest metros showed that highly-educated, higher-paid workers were more likely to be able to work from home and generally had smaller activity spaces (as measured with mobile phone GPS data).

In the popular imagination, those most at risk of the virus were essential workers: medical, first-response, and critical infrastructure workers who needed to break stay-at-home orders in order to ensure that more people didn’t die. We put up yard signs, made crafts, and gave them free things to admire their bravery.

Yet COVID-19 arguably didn’t disproportionately kill medical first-response workers: Research from Cal-Berkeley suggests that workers with the highest excess death rate were those who prepared take-out dinner, harvested food, sorted deliveries, and built homes. One Massachusetts study did find the highest raw death rate for health care workers, but only a certain type of health care worker. “Health care support” workers, which includes orderlies and nurses’ assistants and other positions with extensive patient contact, died at the highest rate; their rate was four times higher than “health care practitioners”, the much more highly paid positions who could in some cases work remotely.

The types of jobs with high COVID-19 fatalities—construction, food preparation, health care support—are often done by Black and Brown Houstonians. The most recent ACS data show that working-age Black Harris County residents fill 48% of health care support positions despite being 20% of the population. Per 2018 Census department data quoted in a Houston Chronicle story, Hispanic Harris County residents represent 50% of its food service workers and 81% of its construction workers. And as mentioned above, they are also more likely to live in overcrowded homes.

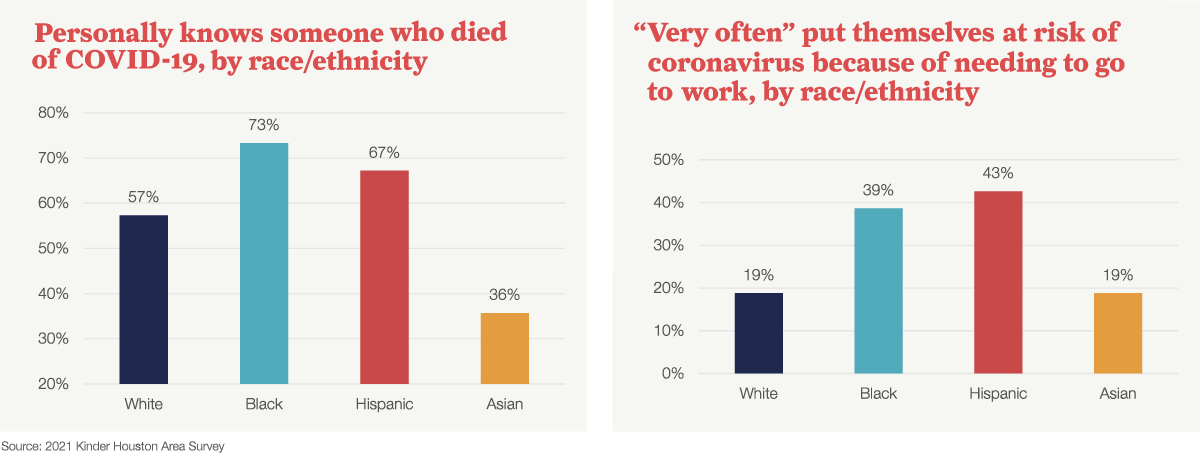

Our own 2021 Kinder Houston Area Survey showed that Black and Hispanic residents were more likely to get sick at work, and therefore risk bringing the disease home to relatively crowded homes.

For this year’s survey, we asked if people needed to put themselves at risk of exposure to COVID-19 and go to work, lest they risk losing income. The responses show a large race/ethnicity gap: 39% of Black and 43% of Hispanic respondents stated they needed to do so “very often”, much higher than other racial/ethnic groups. Black and Hispanic respondents were also more likely to be personally affected by the disease.

This blog post’s analysis, linking workplace conditions, housing conditions, and the virus’s spread, may seem too little and too late. The state has reopened, indoor dining and large events are at capacity, and schools are fully reopening to in-person.

What could have been done differently to address this—aside from creating a more equitable and affordable housing system to begin with? Expanded unemployment benefits helped people remain at home, though those benefits did not extend to all workers (such as undocumented workers) and required bureaucratic wrangling. The benefits have now expired after mass vaccines became available.

On the housing end, an eviction moratorium at the state and national level helped, but the state moratorium is set to expire soon, too. Additionally, many college campuses had quarantine dorms set up during the outbreak. To bring this idea to scale outside of the academy, one could use empty hotel beds as places where a person could safely quarantine. The idea proved successful in Taiwan, where it was implemented nationwide in a country which remains uniquely unaffected by COVID-19. But here in the States, neighbors protested one such hotel in the Seattle suburbs early in the pandemic. In Houston last year, the city government offered at least 586 hotel rooms to quarantining first responders, but that privilege only extended to frontline workers and not people in overcrowded homes.

Where would these hotels go? How could the state reach people who needed housing, and how could it get these people to trust the facilities? Who would pay for it all? Land-use laws, NIMBYist governance, and a crass profit motive may get in the way of these and other potential infection-slowing policies. Someone may answer the question about how to effectively use resources to slow the disease’s spread. But one lesson learned is that while we share a lot of air with our coworkers and housemates, we are not all in this together.