It’s growing faster than any other megaregion. In important respects it’s also growing apart from other megaregions, in its increasing economic diversity, the relative youth of its population, and the pragmatic approach of its local politics. And it represents a harbinger of the challenges and opportunities all U.S. cities will face as they experience rapidly rising ethnic diversity.

Urbanist scholar Richard Florida has popularized the idea that the most important geographic units driving the U.S. economy today are neither states nor cities, but megaregions. America’s megaregions are vast urbanized areas, in some cases crossing state boundaries, with multiple metropolitan areas in relatively close proximity to one another. As Florida has shown, the megaregions are where the action is. They are the country’s most powerful geographic engines of innovation and growth, and its most potent magnets for talent.

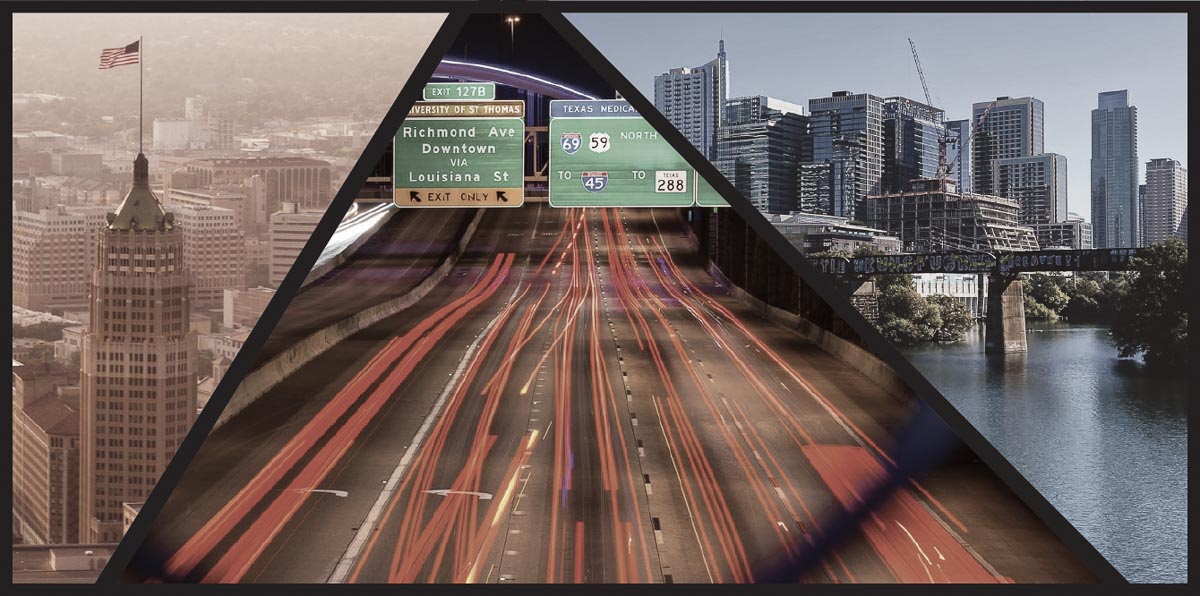

For our newly released book, "The Texas Triangle: An Emerging Power in the Global Economy," Henry Cisneros, David Hendricks, Bill Fulton, and I built a proprietary dataset comparing the Texas Triangle with the rest of America’s eight largest megaregions: the Northeast Corridor, the Urban Midwest, the Urban Southeast, Southern Florida, Southern California, Northern California, and the Pacific Northwest. Together, the top eight megaregions as we define them account for half of America’s population and more than half its economy.

Within each megaregion, the major metro areas have far stronger economic connections to one another than to metros elsewhere in the country, and they increasingly resemble each other in demographic and economic respects. As a result, each megaregion has its own distinctive “personality.” And more and more, America’s megaregions are competing with one another—for talent, for business, and even for political and cultural influence throughout the nation.

In "The Texas Triangle: An Emerging Power in the Global Economy," the Texas Triangle is compared with the U.S.'s other megaregions: the Northeast Corridor, the Urban Midwest, the Urban Southeast, Southern Florida, Southern California, Northern California and the Pacific Northwest.

Map courtesy of Texas A&M University Press

Two conclusions about the modern-day Texas Triangle stand out:

First, the Triangle represents a thoroughly distinctive set of demographic and economic realities—a model unlike any other. It’s younger, faster growing, less White, more Hispanic, slightly less educated, more economically expansive and diverse, more lightly taxed, more permissive in its land-use and business-regulation policies, and more affordable for families and businesses than its megaregion peers. In these respects, the Triangle conforms to a number of widely held stereotypes about Texas.

But our analysis also shows–and our book documents in depth–that the Texas Triangle increasingly defies many common stereotypes. While the image of Texas as a low-tax, low-service, low-amenity state is partially accurate, it’s a mistake to suppose the Triangle owes its economic success to having a cheap, if undereducated, workforce. As we’ve pointed out, the Texas Triangle’s White, Black, and Asian American populations have higher education attainment levels than their peers in the other megaregions, and people earn more, on average, than their peers with comparable educational attainment elsewhere. And as we show in our book, the popular image of Texas as a deep-red bastion of ideological conservatism bears little relationship to the emerging urban realities of the Texas Triangle.

At the same time, it’s also a mistake to assert—as national media commentators sometimes do—that urban Texas is becoming more like urban centers on the coasts as it grows larger and more ethnically diverse. On the contrary, the Texas Triangle metros are growing apart in some important ways from regions like the Northeast Corridor and Northern California. The Triangle is becoming more economically diverse as the coastal regions grow more concentrated. Gaps between the Triangle and its coastal peers on economic policy, housing, and infrastructure are expanding, not shrinking. Despite the relatively young and diverse populations in the four Triangle metros—and their solidly blue political complexion in national elections—they have sustained a centrist, pragmatic style of local politics as coastal metros become decidedly more progressive.

A second conclusion from our analysis is that the Texas Triangle metros—like the metros in the other seven megaregions—are more similar to one another than they are to places anywhere else, despite their varying histories. Yes, there are a few differences among them: Austin has considerably higher educational attainment levels than the other three, San Antonio has better housing affordability, and Houston has a less diversified economy.

But they generally share common strengths as well as common weaknesses, like high population shares without health insurance and relatively weak scores for outdoor amenities on measures like The Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore index. Most importantly, they are struggling to raise educational attainment levels among their homegrown populations—especially in their fast-growing Hispanic communities, which often face language barriers as well as inadequate investment by the state in urban schools serving lower- to moderate-income students. Consequently, the Triangle metros are overly dependent on importing the high-skilled workforce that’s powering the megaregion’s explosive growth from other parts of the United States.

On the other hand, the Texas Triangle metros share a key advantage over other megaregions: They constitute an increasingly integrated economic system within a single state, which means they have better opportunities than most to forge a coordinated agenda for addressing their challenges. A central question for the future will be whether the Triangle metros and the state of Texas can work together on their shared priorities around education, housing, infrastructure, and economic development.

The Texas Triangle is emerging as a truly distinctive geographic unit, quite different from the state’s own historical experience and unlike other American megaregions. It represents a model for how to accommodate rapid population growth and high ethnic diversity while sustaining economic dynamism and keeping middle-class lifestyles more in reach than they are in most other places. The Triangle also bears watching as a harbinger of challenges other U.S. urban regions will face as they become more diverse. Still, the surging growth of the Texas Triangle ensures that it’s poised to play an increasingly powerful role in American society and in the world economy.

J.H. Cullum Clark is the Director of the SMU-Bush Institute Economic Growth Initiative in Dallas.