City Observatory recently ran a commentary by Jason Segedy titled “The Great Disconnect,” in which he expresses his deep dissatisfaction with the ongoing debate over gentrification in America.

Segedy, who is the director of planning and urban development for the City of Akron, challenges the broad brush used to paint the portrait of gentrification in midsize and large cities alike. He maintains that the gentrification narrative is perpetuated by journalists and academics in large, thriving cities on the east and west coasts — New York, Washington, D.C., San Francisco — where, indeed, large numbers of low-income residents have been displaced. However, Segedy argues, the trouble with the portrayal is that the real problem the majority of U.S. cities face is the concentration of poverty — not the concentration of wealth.

Segedy is a lifelong resident of Akron, a midsize city that, like many in the middle of America, has experienced economic decline and the gradual slowing and net loss in population growth. Much of what is written about gentrification, he contends, went from “thought-provoking and well-reasoned” to “intellectual dishonesty, irrational hysteria, and even self-parody, particularly when it is applied to the long-suffering cities of the Rust Belt.” As a neutralizer, he recommends a report from the University of Minnesota Law School’s Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity called “American Neighborhood Change in the 21st Century: Gentrification and Decline.”

Focusing on population growth and decline, the influx and reduction in income levels, race, education and more, the report examines the extent of economic expansion or decline, low-income displacement and concentration and abandonment by census tract in the 50 largest U.S. metropolitan areas between 2000 and 2016.

Some of the more striking findings include:

► The most common form of American neighborhood change, by far, is poverty concentration. About 36.5 million residents live in a tract that has undergone low-income concentration since 2000.

► On net, far fewer low-income residents are affected by displacement than concentration. Since 2000, the low-income population of economically expanding areas has fallen by 464,000, while the low-income population of economically declining areas has grown 5,369,000.

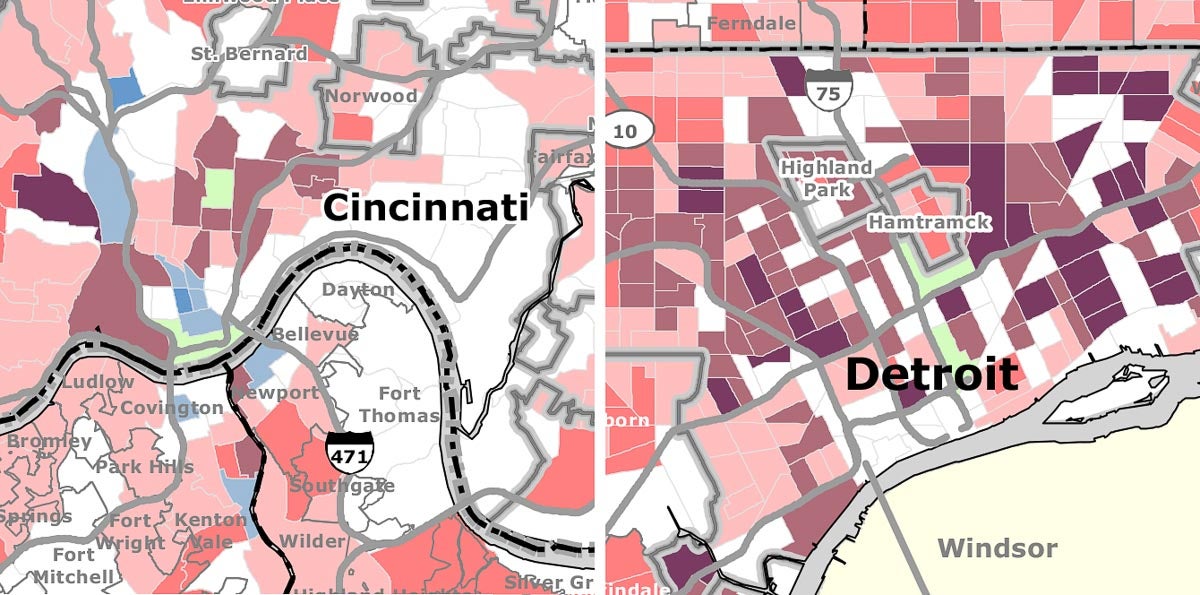

Large portions of the populations in “Rust Belt” cities and regions in the Midwest, such as Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and Milwaukee, live in areas where poverty concentration has occurred. In the Detroit region, 49% of residents live in such an area, according to the report, which categorizes low-income census tracts as those that are economically declining and have seen an increase in the low-income population. When looking at just the central city of Detroit, that percentage goes up to 56%. In Akron, where Segedy lives, 65% of residents live in areas of low-income concentration.

In Cincinnati, 57% of residents live in a neighborhood in which low-income concentration has occurred. Detroit has a similar problem with concentrated poverty — 56% of its residents live in areas of low-income concentration.

Source: American Neighborhood Change in the 21st Century: Gentrification and Decline

Where gentrification remains an issue

About 9.5 million people in the 50 largest U.S. metros live in neighborhoods that have experienced low-income displacement. Nationwide, these tracts are predominantly found in the central cities of metropolitan areas.

Most of the places where low-income displacement — a consequence of gentrification — has been a significant trend are coastal cities, including Boston, Long Beach, Los Angeles, New York City, Oakland, Portland, Seattle and San Diego, among others. In these are cities, more than 10% of the population lives in neighborhoods that are expanding economically while also experiencing net declines in low-income population — changes normally associated with gentrification. (In other words, as more higher-income residents move in, economic changes such as increased rents and property taxes force lower-income residents to move out.)

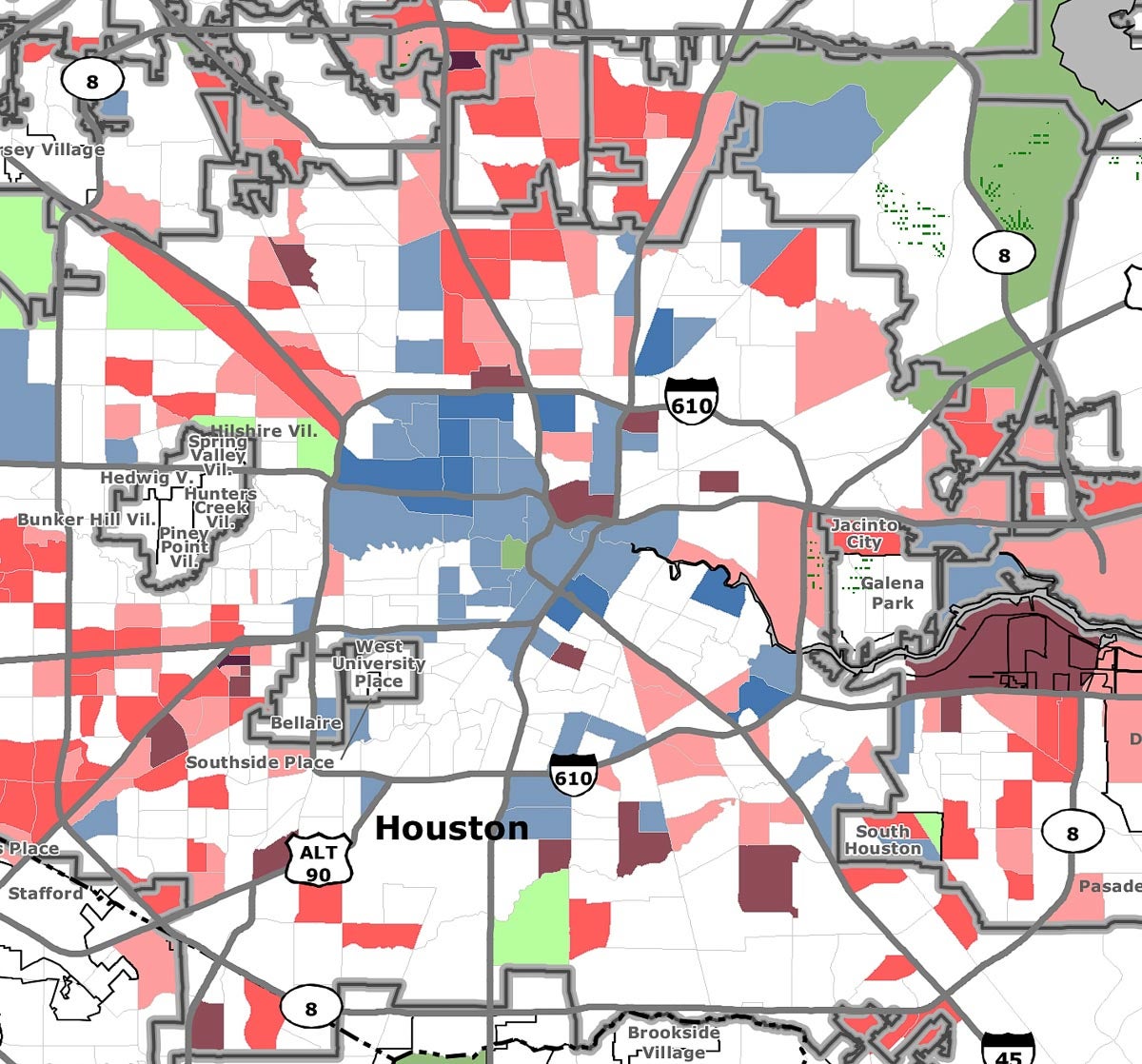

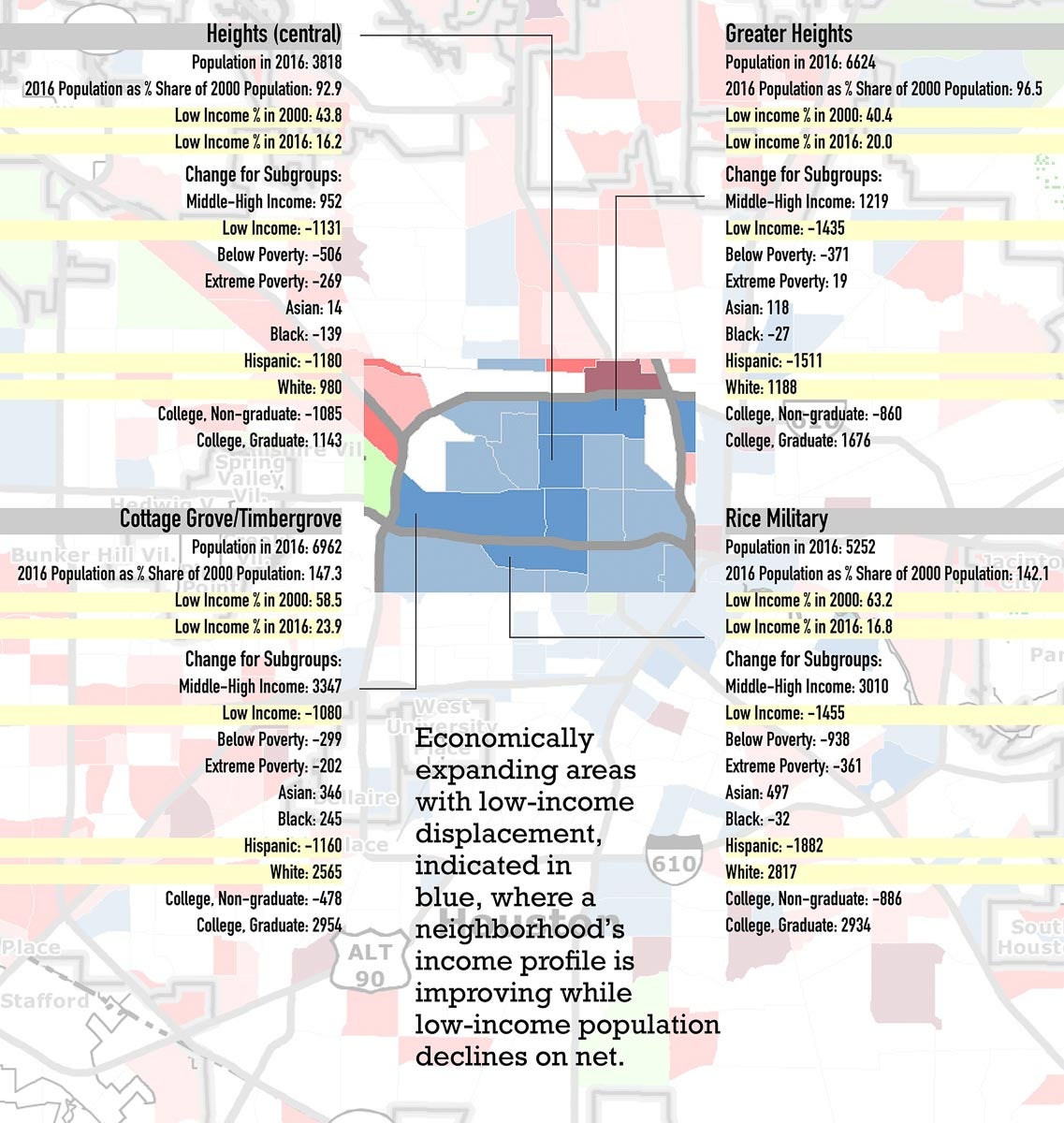

Some exceptions to the coastal norm are Atlanta, Denver, New Orleans, Saint Louis, Austin and Houston. Here, 12% of the population and 8% of the city’s low-income residents live in a strongly economically expanding area. According to the IMO findings, on net, those neighborhoods have experienced a lot of displacement: their low-income population has dropped 25.7%, their population in poverty has fallen by 22%, their non-college-educated population has fallen 10% and their Black population has decreased by 12%.

Neighborhood change in Houston mapped by individual census tracts (click the image to view the entire map):

Blue: Economically expanding areas with low-income displacement

Green: Economically expanding areas with overall growth

Purple: Economically declining areas with abandonment

Red: Economically declining areas with poverty concentration

Source: American Neighborhood Change in the 21st Century: Gentrification and Decline

In contrast, between 2000 and 2016, the overall population of these Houston neighborhoods has grown 14%, with a 48% increase in the white population and a 204% increase in the Asian population.

An analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas earlier this year showed Houston was gentrifying more quickly than the other large Texas metros. From 2000 to 2015, the median income in areas less than 3 miles from downtown went up by 67%.

Across the Houston region, there are 120 economically expanding neighborhoods, and 84 of those have experienced low-income displacement.

The Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity report also shows different trajectories for urban and suburban neighborhoods experiencing strong economic expansion in the Houston area. Inside the Loop, “a large swath of neighborhoods — beginning with East Downtown and extending north and west to the I-610 (Loop) — have shown significant low-income displacement.” Meanwhile, economically expanding suburban neighborhoods have seen “broad population growth, including growth in the number of low-income residents.”

In the suburbs of Houston, neighborhoods experiencing strong economic growth have seen their populations increase 187%, including a 48% spike in low-income residents. In short, these areas are showing strong economic improvement without displacement. As the “American Neighborhood Change” report points out, most places experiencing growth similar to neighborhoods in suburban Houston without displacement are “typically places with significant new housing construction, where residents across the income spectrum are arriving.”

Data source: American Neighborhood Change in the 21st Century: Gentrification and Decline

Concentrated poverty in Houston

Displacement is placed in the larger, regional context by the IMO report: “People who leave one neighborhood have to go somewhere else; if displacement is making one area richer, it is probably making another area poorer, or at least, concentrating existing poverty. Neighborhood change isn’t just about one specific neighborhood, but about population flows across a region.”

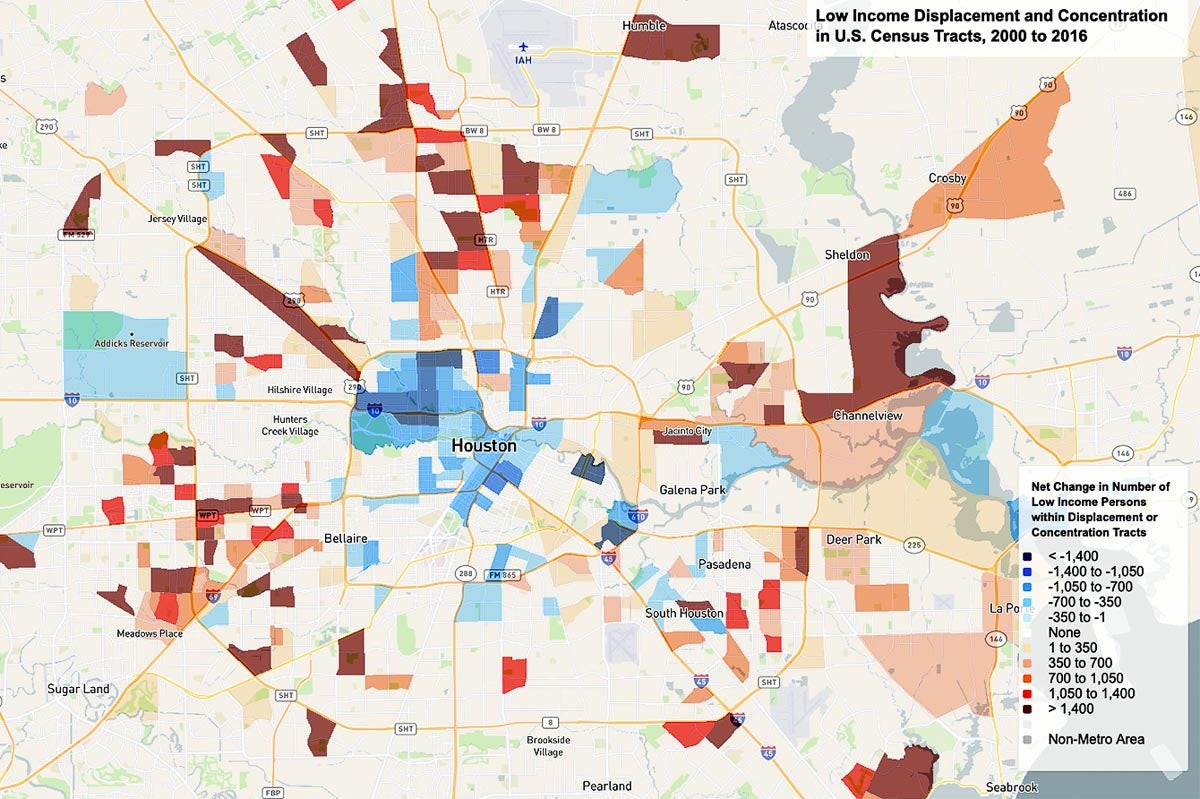

In the 50 largest metros combined, 36.5 million people live in a census tract that has undergone low-income concentration since 2000, the report shows. More than 24.4 million of those tracts are in suburban areas.

Approximately 1.2 million people in the Houston metropolitan area live in the 244 neighborhoods categorized as economically declining. More than half of those — 55% — live in Houston, but outside of the 610 Loop. The other 45% are in the suburbs.

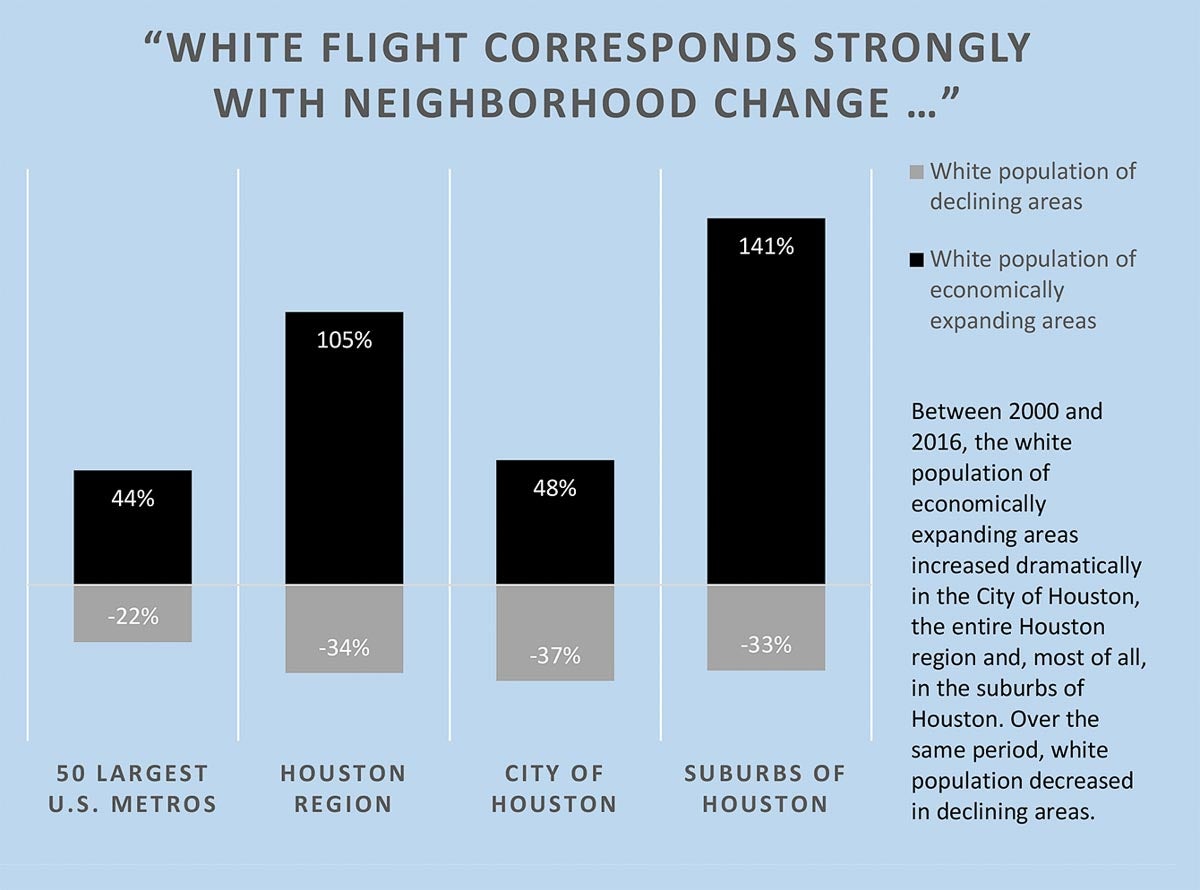

Since 2000, the low-income population in strongly declining Houston-area neighborhoods has grown by 40%. There has been a large increase — 41% — in the number of Hispanic residents in these areas, the IMO report shows. At the same time, there’s been a significant exodus of white residents, amounting to a 34% decrease in that population. The map below shows these neighborhoods encircling the Loop, but located farther out, closer to Beltway 8.

An interactive map shows changes in the population of each census tract of the 50 largest U.S. metropolitan areas from 2000 to 2016, including overall population, income levels, race, education and more.

Source: American Neighborhood Change in the 21st Century: Gentrification and Decline

Almost 30% of Houstonians and more than 40% of the city’s low-income residents live in neighborhoods experiencing strong decline. And though these areas of economic decline only grew 2.2% from 2000–2016, their low-income population increased 32%, their population in poverty jumped 53%, their non-college-educated population went up 10% and their Hispanic population increased 34%. During that period, the white population decreased 37%.

In 2018, Jie Wu and other researchers at the Kinder Institute released a deeper dive on the issue in Houston in their report “Neighborhood Gentrification Across Harris County, 1990–2016.”

Among their findings:

► Gentrification across Houston has accelerated since 2000. Very little gentrification occurred from 1990 to 2000, while the period between 2000 and 2010 saw the greatest change. Growing gentrification patterns emerge during the time period between 2010 and 2016.

► Many gentrified neighborhoods are inside the 610 loop (73 out of 783 census tracts1 in Harris County), but a greater number of gentrified neighborhoods are outside the 610 loop (144 census tracts).

The study also included an investigation of what neighborhoods were most susceptible to gentrification. What they found in that analysis was almost all inner-Loop neighborhoods on the east side of Houston “are susceptible to gentrification in the near future.”

Unlike the IMO report, displacement was not measured in the Kinder Institute study. In the latter, displacement is called out as a consequence of gentrification; however, “most aggregate data are unable to capture and estimate the true loss of low-income residents in a given neighborhood, in addition to their reasons for moving. Not all moves out of a changing neighborhood count as displacement.”

The Kinder Institute analyses found an uneven distribution of gentrification across Harris County neighborhoods. “Scarce affordable housing in higher-demand locations creates a tight housing market, exacerbating effects of gentrification,” according to the report. Factors such as socioeconomics, housing, transportation and location impact an area’s susceptibility to gentrification.

The Houston area’s specific combination of socioeconomic and cultural diversity as well as sprawling residential patterns has led to a unique set of challenges, according to Kinder Institute researchers. The inventory of affordable housing has been diminishing. In addition, the researchers found that some neighborhoods susceptible to gentrification are in flood-prone areas, which could possibly exacerbate the risk of gentrification.

To understand how the region’s housing system is changing over time, the Kinder Institute has begun publishing an annual “State of Housing in Harris County and Houston” report. The project brings a wide range of housing-related indicators into one place and makes them accessible to all. The report synthesizes several key issues and indicator data that are available at the county and city level as the neighborhood level (via the Houston Community Data Connections site).

While the Greater Houston area has a reputation for housing affordability, many of the findings of the housing report indicate this affordability is disappearing in the city of Houston and Harris County. Much of the tightening in the housing market is the result of rising home prices and rents.