Residential segregation is the lynchpin of racial inequality in U.S. metros. It drives unequal access to quality education. It significantly drives the large wealth gaps that exist between racial groups (now, somewhere on the order of a 20 to 1 advantage for whites compared to Blacks or Hispanics—double the 10 to 1 advantage in the 1980s).

This extreme wealth gap occurs in part because of greater demand for white neighborhoods, which drives up their housing value, and in part because of racially biased appraisal processes, which new research from former Kinder Institute associates Junia Howell and Elizabeth Korver-Glenn finds has grown since 1980.

Analyzing data for the 107 U.S. metros with populations of more than 500,000 people from 1980 to 2015, they compared appraisal values of homes owned by whites and by persons of color. Using statistical techniques, they were able to compare the change in appraised values of comparable homes in comparable neighborhoods in comparable metro areas. The only difference: the neighborhood racial composition.

Howell and Korver-Glenn found that from 1980 to 2015, homes in white neighborhoods increased in value on average $194,000 more than in neighborhoods of color. What is more, the rate of the gap in assessed values of these comparable homes in comparable neighborhoods is getting larger over time. This is substantial—and unearned—wealth creation for white homeowners, and it’s due to racial segregation.

For the past 20 years, my colleagues and I have studied why we have racially segregated neighborhoods. We know why we had them in the past: it was the law in many places and racially biased practices—such as redlining and restrictive covenants—were commonplace.

But such practices were outlawed in the 1960s. We have had a lifetime to integrate. Yet, we have had little change. In fact, as Junia Howell and I found in our recent study, once we account for the growing racial diversity of our nation’s metros, we are actually more segregated now than we were in the 1960s.

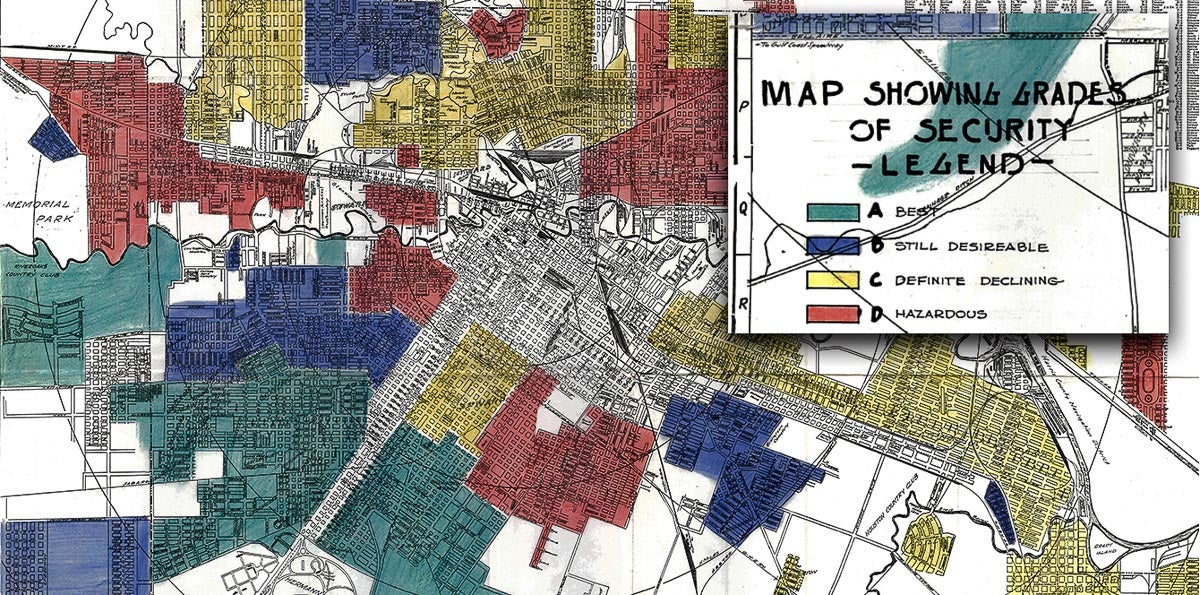

In 1937, the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation created this map of Houston neighborhoods that reflected their “mortgage security.”

Much research has turned to looking at people’s preferences — Where do they want to live? Who do they want to live with? Do they achieve their preferences where they actually live? My colleagues and I repeatedly find the same results across time and across metros. I summarize it like this:

White Americans overwhelmingly live in majority-white neighborhoods. When asked why they live where they do, we find the following:

1. Though often communicating a preference for diversity, most whites’ definitions of diversity are quite limited — not more than 20% non-white — meaning that even if their definitions of neighborhood diversity were realized, they still would live in overwhelmingly majority-white neighborhoods.

2. Whites actually live in neighborhoods with less racial diversity then they communicate they desire.

3. Whites often operate only in a white network of friends, realtors and family showing them white neighborhoods.

4. While whites say they don’t mind living with African Americans and Hispanics per se; they mind living where crime is high, educational quality is low, the neighborhood looks unkempt or housing values are declining. Because whites see these characteristics as true of most Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, they avoid considering such neighborhoods. This is called the proxy claim for avoiding diverse neighborhoods. It is not racial composition, we are told, it is the proxies associated with race.

Substantial research over the past twenty years using sophisticated experimental methods has found that despite the proxy claim, whites avoid living with blacks and Hispanics regardless of crime levels, neighborhood appearance, educational quality, or housing value changes. As I noted in a recent New York Times piece, “Most white Americans simply cannot imagine there are Black or Hispanic neighborhoods with low crime, with high-quality schools, with rising housing values, and that look well-kept. Despite the fact that there actually are such integrated neighborhoods that I have lived in myself, any mention of a high percentage Black or Hispanic (usually 30 percent or more) overwhelms their senses and emotions and signals ‘AVOID!’ no matter what else they are told about the neighborhood.”

Now, here is the crux of the issue. When we study Black and Hispanic preferences for neighborhoods, they desire the same as white Americans: low crime, attractive neighborhoods, thriving schools and increasing housing values. And they too want to live in racially diverse neighborhoods. But here the similarities end.

African Americans’ and Hispanics’ definitions of racially diverse neighborhoods are far more racially diverse than whites’ definitions. Their definitions of diversity typically range from 50%–75% of the people being of different racial groups. We also find that in selecting neighborhoods, they do not try to avoid specific racial groups, unlike whites.

But in the end African Americans and Hispanics, as groups, are not able to realize their preferences, at least involving living with whites. As Blacks and Hispanics are seeking quality and racially diverse neighborhoods, whites are seeking white neighborhoods. It ends up being a game of cat and mouse, a game that thus far has no end in sight.

Racist misconceptions and misinformation lead to fear

This game has severe consequences for our cities and suburbs. Let me share my own experience with these consequences. In 2006, my wife, four children and I moved to a nice neighborhood in the Houston area — a newly built neighborhood with newly built schools. At first, it was quite racially diverse. Too diverse, it turns out, for our white neighbors. In short order, we watched them put their houses up for sale and move out. As one such owner told me as he was loading his moving truck, “If there were 20 more Emerson families in the neighborhood, perhaps we could have stayed.”

Within just a couple of years, our neighborhood was 80% African American and 16% Hispanic. Our local schools — where our four children attended — were quality schools. Yet we noticed that whenever we heard whites outside of our immediate neighborhood talk about the schools, they talked about them as “ghetto schools,” “unruly” and “poor performing,” even though none of those characterizations were true.

After seven years of living in our neighborhood, we were moving to Denmark for a year to teach Urban Studies. We looked into renting out our house in Houston while we were gone. We were told by several experts that we would not be able to rent our home for the amount of our monthly payment. So, we decided to sell our house. It was an attractive, well-kept 5-bedroom, 4-bathroom home on a little lake, surrounded by other attractive homes. We had purchased it for $273,000.

The best offer we got was $225,000, and we agreed to sell at that price. But when the appraisal said our home was only worth $160,000, due to using “comps” in our now overwhelmingly black and Hispanic neighborhood, we could not sell our home for $225,000 (at that price, a buyer would have had to pay in cash). In the end, we had to sell our home for what the appraisal said it was worth (so much for individual initiative). We lost $113,000 in the process. That hurt.

The damage done by our segregated residential system

Racial segregation has consequences. It overwhelming produces unfair advantages for whites and unfair punishment for people of color. Lest you think my story particular only to me, recall the new study I noted at the beginning of this essay. My story is a common experience across U.S. metros for those who don’t live in white neighborhoods, and it is getting worse. As we’ve seen this summer, it also, in part, produces unrest, anger and — in its worst forms — violence that is erupting across our nation’s metros.

We have two choices. We can bury our heads in the sand and act as if segregation is innocuous. Or we can admit we have challenges, roll up our sleeves and overcome them.

It’s time to face the prejudices we hold of fellow citizens. It’s time to end our excuses for why it is OK to avoid fellow human beings. It’s time to stop the destructive inequality of our current segregated residential system.

Instead, it is time to be a true community, drawing on our full strength. It is time to be change agents. It is time, finally, to be Americans, together.

Michael O. Emerson is head of the Department of Sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is the former academic director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research and a former professor at Rice University.