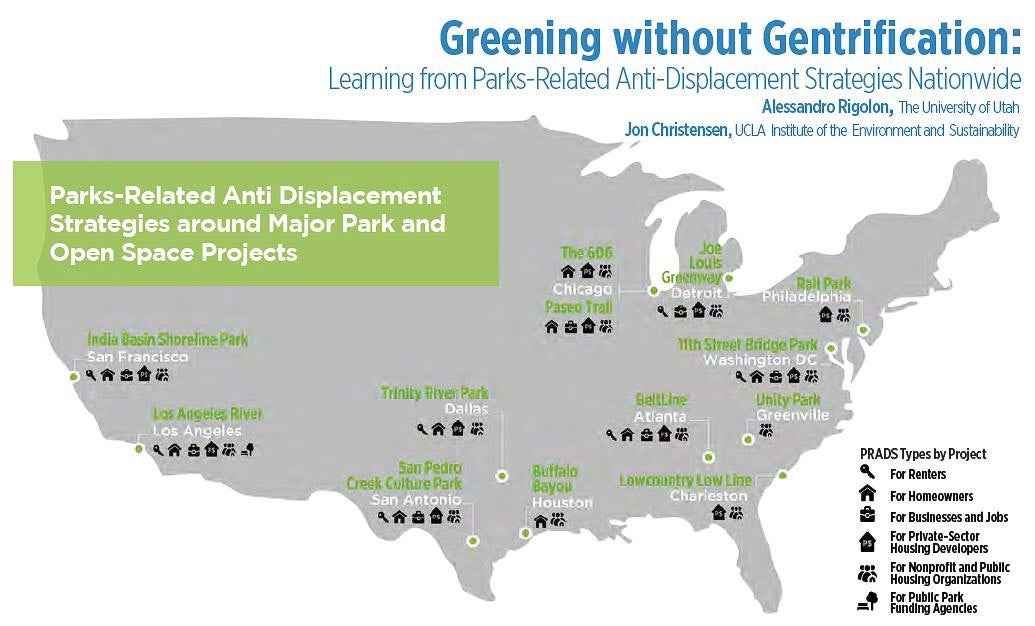

The report is from Alessandro Rigolon, a professor of city planning at the University of Utah, and Jon Christensen, a professor at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and it surveys "parks-related anti-displacement strategies" or PRADS implemented by 19 American cities where 27 major park developments are underway, including Houston's Buffalo Bayou, Dallas' Trinity River Park, Atlanta's BeltLine, Los Angeles' Los Angeles River, and others.

"We were actually quite surprised to see so many project stakeholders in Sunbelt cities (in politically conservative states, excluding California) to implement anti-displacement strategies related to parks," Rigolon said to me in an email. "In the report, we note that the implementation of PRADS can be hindered or supported by state laws (and even city and county laws)."

"Texas cities do have some limitations from state policies (and politics)," he continued. "But they can certainly lead the effort to green without displacement by showing ways to work around state-level limitations. In that sense, they can develop creative solutions that perhaps can show the way for other cities in red (or purple) states."

The researchers found 26 strategies within six broad categories describing three populations benefiting from PRADS—renters, current and prospective homeowners, and businesses and workers. Additionally, there are three populations that "play a central role" in implementing PRADS—private sector developers, nonprofits and public housing organizations, and park funding agencies. The report's 26 strategies focused on stabilizing changing neighborhoods, including citywide rent control, anti-eviction measures, foreclosure assistance, homebuyer loans, inclusionary zoning, developer density incentives, community land trusts, funds to build permanent affordable housing around new parks, and others. A more in-depth look into some of these strategies can be found in Monday's Urban Edge post here.

Rigolon and Christensen's findings are neither positive or negative. "The good news is that stakeholders in about half of the projects we surveyed, including many park advocates and local community organizations, are proposing and actually implementing PRADS,” the report says. “The bad news is that the other half of the projects have not taken concrete actions yet.”

While each city highlighted by the report had a different combination of strategies implemented, every city had nonprofit and public housing organizations implementing strategies like housing trust funds, community land trusts, and other forms of land banking, and value capture mechanisms, such as tax-increment financing, which generate funds for affordable housing.

"In the report, we noted that the strategies need to be based on the local context (including state of the housing market, state laws and policies, etc.) and community input," Rigolon said. "That said, we argue for a combination of strategies that focus on both affordable housing and jobs. In addition, cases like the Atlanta BeltLine, which initially only focused on the production of new affordable housing, show that focusing on production only (and not preservation) might not be sufficient unless there are significant funds to support the creation of a very large number of new affordable housing units."

While each city had its own combination of strategies (with neither being more or less efficient), Christensen emphasizes the importance of cities getting a head start on combating gentrification rather than being reactionary.

"I would argue that asking for an 'efficient' solution might lead cities astray since what we have found in the field is that a multidisciplinary approach that involves as many of the implementers and beneficiaries as possible seems to be the approach that has the best chance of success," he said. "We also found that the best wisdom in the field is that you have to start early, and you have to do deep, authentic community engagement to build coalitions, and that takes time. It's almost the opposite of efficient, and maybe it's important to recognize that."

"They will all be unique because the context is unique. But the most successful will likely be those that focus on parks as part of equitable community development. That's a multidisciplinary challenge that requires a multidisciplinary approach," Christensen said.