Liz Chiao and Raúl Ramos had to decide; send their children to one of Houston’s dual-language English-Spanish schools or to the newly opened Chinese-language immersion school?

If you ask their son Joaquin whether he’s Asian or Latino, he’ll hold his hands up in a shrug and look back and forth between his palms, back and forth, imitating a biracial character from the television show Blackish who sometimes feels caught between identities.

The school dilemma they faced is a perfectly typical Houston problem. In an effort to serve its diverse student body, the Houston Independent School District recently retooled its bilingual Spanish programming and launched two new language immersion magnet schools for Mandarin and Arabic. Choices in a district where nearly a third of students are considered English Language Learners, choices abound.

“It’s kind of an embarrassment of riches in some ways,” remembers Ramos about their decision. “Ten or so years earlier, you didn’t have that choice.”

For young people and newcomers to the city, it can be hard to picture the Houston that once was. In the 1940s, the city had just under 600,000 people, according to census estimates. The schools were segregated and so were many of the neighborhoods.

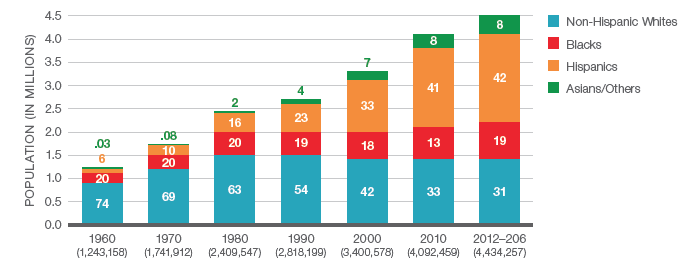

Today, Houston is recognized as the most diverse metropolitan area in the country. It is the country’s fourth-largest city with a population that is more than a quarter foreign-born and 44 percent Hispanic, according to 2016 estimates from the census. "It reminds us of how striking this world is," said Stephen Klineberg, founding director of the Kinder Institute and the author of the annual Kinder Houston Area Survey that has tracked the area's changing demographics and attitudes.

Demographics of Harris County by Decade (1960-2010) and from the American Community Survey Estimates for 2012-2016. Source: Kinder Houston Area Survey.

The city is sometimes described as a melting pot. It’s a common analogy but the melting pot imagery implies each individual ingredient has disappeared as a new mixture - impossible to separate. But as findings from the latest Kinder Houston Area Survey show, the city’s often touted diversity is a layered, complicated story still being written.

Both the children of immigrants, Chiao and Ramos are familiar with Houston’s diversity and it’s part of what they enjoy about living here. But they also experience its limitations. They made the decision to send their kids to a Spanish-language program but started a Skype-based class online to learn Mandarin. For the most part, things went well. But with so few Asian classmates at their school, Ramos said, “they got singled out for being Chinese." They were teased for the shape of their eyes and the foods they brought from home for lunch.

For Chiao, a doctor with a research focus on HIV, and Ramos, a history professor at the University of Houston, exposing their kids to all Houston has to offer is important. “You can take your kids and do some really cool things...we have access to a lot of diversity and culture,” said Chiao, “but I think ultimately the way some of it plays out, we end up still quite segregated.” Chiao sees it at her work too, where she treats some of the area’s most vulnerable patients. They also tend to be overwhelmingly black or Hispanic. Experiences like these have shaped how their family sees the city and their place in it.

Findings from the latest Kinder Houston Area Survey also suggest that an individual’s identity, including their race, ethnicity and age, shape their experiences and attitudes. The responses offer insights into the nuances behind Houston’s slogan-worthy diversity.

White Harris County residents, for example, perceive things like opportunity and interethnic relations differently than other racial and ethnic groups in the annual survey findings. Nearly 60 percent of white respondents and U.S.-born Hispanic respondents in Harris County, for example, said that relations between different ethnic and racial groups were good or excellent, according to the 2018 survey. Only 42 percent of black residents, 44 percent of foreign-born Hispanic respondents said the same. At the same time, 63 percent of white respondents agreed that “blacks and other minorities have the same opportunities as whites in the U.S. today,” while only 37 percent of black respondents said the same.

It’s not just Houston. In a 2016 Pew Research Center poll 43 percent of black respondents were doubtful the country would ever achieve racial equality.

Some of the survey’s findings suggest younger generations are increasingly accepting of the area’s growing diversity. But parallel to that shift have been trends like colorblind racism and a tendency to confuse naming racism as racism itself. "By claiming that they do not see race," sociologist Adia Harvey Wingfield wrote in the Atlantic, "they also can avert their eyes from the ways in which well-meaning people engage in practices that reproduce neighborhood and school segregation, rely on “soft skills” in ways that disadvantage racial minorities in the job market, and hoard opportunities in ways that reserve access to better jobs for white peers."

Jessie Smith understands this well. “You say you don’t see race, but of course you do,” said the recent University of Houston graduate. As a kid, Smith, who moved to Houston as a young child, remembers attending meetings for the National Association for Advancement of Colored People with his grandparents. Later, a student at University of Houston he carried that legacy with him, becoming the student leader for the group’s campus branch and involved in student government.

Like many young Houstonians, Smith grew up in diverse settings. In some ways, his own story exemplifies the change that has occurred in the country and city. He attends a school his mother couldn’t. It’s an opportunity she didn’t have and representative of the world he lives in.

But Smith’s experiences have also been shaped by enduring racism. He can recount multiple episodes on campus of black students being treated differently, like the night of President Obama’s first election when he said black students celebrating got harassed by the police.

Survey responses suggest young adults like Smith are among the most optimistic about the state of relations between ethnic and racial groups. Sixty-two percent of respondents between the ages of 18 and 29 said “relations among racial or ethnic groups in the Houston area” were either good or excellent and 51 percent of respondents between the ages of 30 and 49 agreed. That’s compared to just 44 percent of respondents between the ages of 45 and 59 and 48 percent of respondents over the age of 60.

“There’s something about the further we get from the age of formal segregation that I think creates this cultural expectation that we are really beyond race in a real way,” said Jenifer Bratter, a sociologist at Rice University who studies race and identity.

In promoting diversity, institutions often place an emphasis on the individual. But that can obscure the broader ways in which race and ethnicity are still stratifying lived experiences. Nationally, most adults surveyed said it was individual racism and not institutional biases that was “the bigger problem when it comes to discrimination against black people,” according to a 2016 Pew Research Center poll.

“I think it’s a lot harder for folks to get their heads around those types of biases operating today,” said Bratter, “particularly in an environment where it’s so diverse.”

But the survey shows large differences in experiences of diversity. While just 37 percent of white respondents in Harris County said they thought white people experienced discrimination sometimes or very often, 85 percent of black respondents said the same thing about black people in the Houston area. Meanwhile 76 percent and 72 percent of Hispanic and Asian respondents said the same thing.

Overall, roughly half of Harris County respondents said they had been in a romantic relationship with someone of a different background, according to the latest survey and that number tends to increase as respondents get younger.

But Bratter cautions interpreting relationships as signs of inherent progress. Intermarriage, for example, is sometimes held up as a barometer of social progress. But it’s a more complicated statistic than that. Houston, for example, with all its diversity, doesn’t have the highest rate of intermarriage in the country, according to a recent report from the Pew Research Center. Though the rate is increasing, it doesn’t even have the highest rate in Texas.

“We have this trend toward more mixed couples,” explained Bratter, so, “clearly this must mean race as a stratifying feature is diminishing. “Not quite,” she says, “You can have intermarriage and still serious racial segregation. And you can have mixed race kids and a lot of racism.”

Houston has had it share of slogans, including, in 2014, “The City With No Limits” from the Greater Houston Partnership. People immediately seized on the ambiguity to parody the city’s infamous sprawl. So far, no slogan has quite fit, which is perhaps why the tagline about Houston being one of the most diverse metropolitan areas in the country has caught on: there’s room for everyone.

But even that narrative can be flattening.

Within the region’s diversity, for example, deep disparities persist from income to schools. The gap between the median household income for white and Hispanic families in Houston was nearly $40,000, according to 2016 estimates from the Census. The gap between white and black households, meanwhile, was more than $44,000. In the school district’s gifted and talented program, Hispanic and black students are underrepresented, while white and Asian students are overrepresented.

When Smith, who plans to get his master’s from Texas Southern University and a law degree from the University of Texas, thinks about the future, he’s encouraged but realistic. Even when it comes to his own racial and ethnic identity, which includes several different heritages, he said he knows how the world sees him. “As a black man, I’m not naïve about that.”

It will take work to bridge those interpersonal as well as structural divides and he wants to do that work. His long-term goals include running for governor. But Smith, himself in his 20s, said, “I’m hopeful for the generation to come after us. Hopefully, they will be able to fix it.”