Photo: Flickr user World Meteorological Organization.

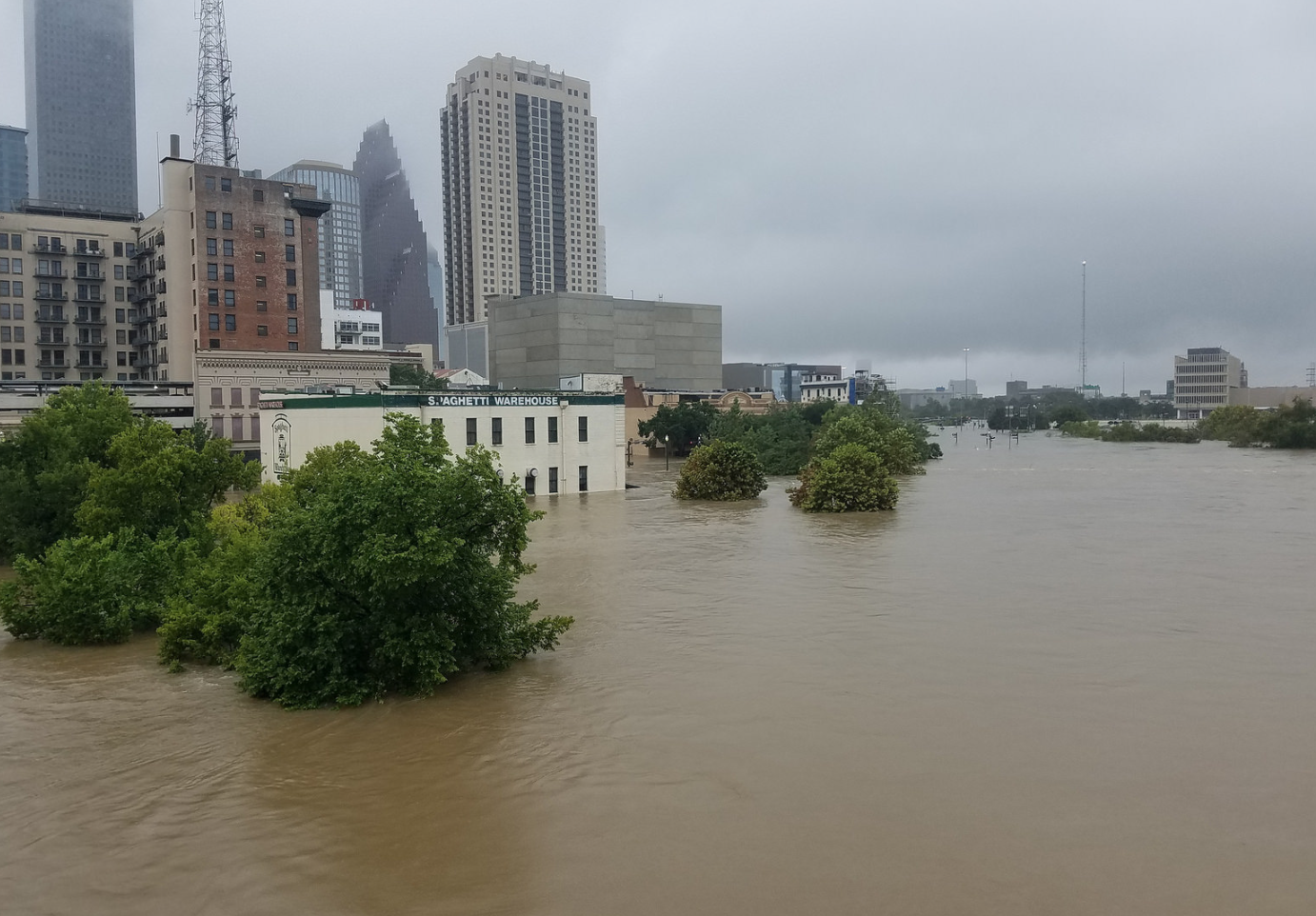

Photo: Flickr user World Meteorological Organization.Hurricane Harvey’s historic downpour on Houston and the accompanying images of flooded streets appearing on TV screens in households across the country have brought analysis over every angle concerning the storm and the city’s preparedness. One repeated object of scrutiny debated by journalists, academics and even the mayor himself, has been the role that Houston’s unique non-zoning system may have played in the city’s flooding.

To be clear: the amount of rain dropped on Houston was a record-breaking outlier whose more than 10 trillion gallons of water would have flooded most cities, regardless of their land use policies. With the similarly extensive flooding that occurred in the neighboring cities of La Porte, Beaumont-Port Arthur, and Katy – all of which have zoning ordinances – it’s clear that few places could have handled a storm of this magnitude.

Harvey aside, the question remains: are Houston’s development policies adequate or do they perhaps worsen the severity of flooding even in more typical storms?

Vulnerable Housing

Existing municipal policy allows for the creation of residences and other structures within 100-year flood zones, which are areas that would be inundated by a flood with a 1 percent chance of occurring in any given year. Though these numbers may sound small, the areas that these flood zones represent are at a significantly elevated risk of flooding relative to the city – one that has only worsened as the frequency and severity of storms has increased with time.

In 2006, Houston City Council amended its municipal code to prohibit new construction and restrict repairs to existing homes in the 100-year flood zones falling along the city’s system of bayous that collectively constitute the city’s floodway system. The resulting political and legal pressures from homeowners located in these zones, whose property values dropped precipitously following the change in policy, led city officials to change course and retract most of those restrictions in 2008.

Following this reversal in policy, over 7,000 new units have been developed in these flood-prone areas – and not without consequences. The development of these new units in bayou-adjacent floodways reduces the land’s ability to carry faster-moving currents of water during a flood, which, in turn, lessens its effectiveness in directing the flow of water away from residential areas. On top of exposing the rest of the city to greater risk due to the reduced floodway capacity, the property owners in these areas (many of whom are unaware of their placement in a flood zone) are exposed to higher velocity waters that create more risk for structures, their occupants and first responders.

Area-specific regulations would go a long way in controlling which structures are built within and adjacent to 100-year flood plains. Future construction should be limited in number and elevated from the ground to protect structures and allow floodways to function optimally. Existing structures should be assessed to determine if they should be retrofitted for flood resistance or if repeatedly flooded structures would make a better investment as retention ponds and green space rather than by being repaired yet again.

Unsustainable Development

Though its constraints on flood-prone building sites may be lax, Houston sometimes over-regulates where it shouldn’t. The city’s high parking requirements, believed to create roughly 30 parking spaces for every Houstonian, create paved areas that altogether constitute a large amount of impervious land through which water cannot be reabsorbed into the ground. Parking requirements (among other policies) also hinder the creation of dense development more generally, which in turn contribute to Houston’s well-known urban sprawl by pushing development outward towards the suburbs.

Although Houston’s flat topography and difficult to penetrate clay-based soil are unavoidable environmental factors that contribute to the area’s propensity for flooding, these factors are significantly worsened by sprawling expansion.

Construction in the Katy Prairie and Houston’s outer areas have significantly contributed to the amount of impervious surface covering the area, contributing to water runoff and making it more difficult to displace water away from the center city. This development also came at the price of effectively paving over much of the prairies and wetlands that are often critical in absorbing rainfall.

A sustainable strategy for Houston’s future should include conservation efforts coupled with environmental engineering. Preserving remaining prairies and wetlands, particularly in Houston’s expanding suburban regions, should be a priority. Development throughout the area should also be balanced with green space featuring native, deep-rooted plants effective at helping control smaller floods.

Planning for Change

Rising water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico combined with increasing moisture in Houston’s atmosphere promise both larger and more frequent storms. Houston has faced three of these 500-year floods in the past three years alone with intense downpours having doubled in frequency in the past decade – many of which have strained or completely overrun the city’s stormwater drainage capacity.

If Houston wishes to maintain its long-held status as a booming, investor-friendly city, then it must take concrete steps toward climate resilience. Stormwater infrastructure investments, environmental conservation and changes to existing policy to encourage smart growth, while discouraging hazardous development, would all go a long way towards protecting the city for years to come.

Alexius Marcano is a graduate student at the New York University Wagner School of Public Service and a research assistant at the Furman Center. He is a former fellow with the Kinder Institute's Urban and Metropolitan Governance program and co-author of the report: Developing Houston: Land-Use Regulation in the "Unzoned City" and its Outcomes.