Smart growth has positioned itself as a centrist solution to population growth: it pleases the left by providing social equity and environmental sustainability and the right with the promise of increased development potential for private developers.

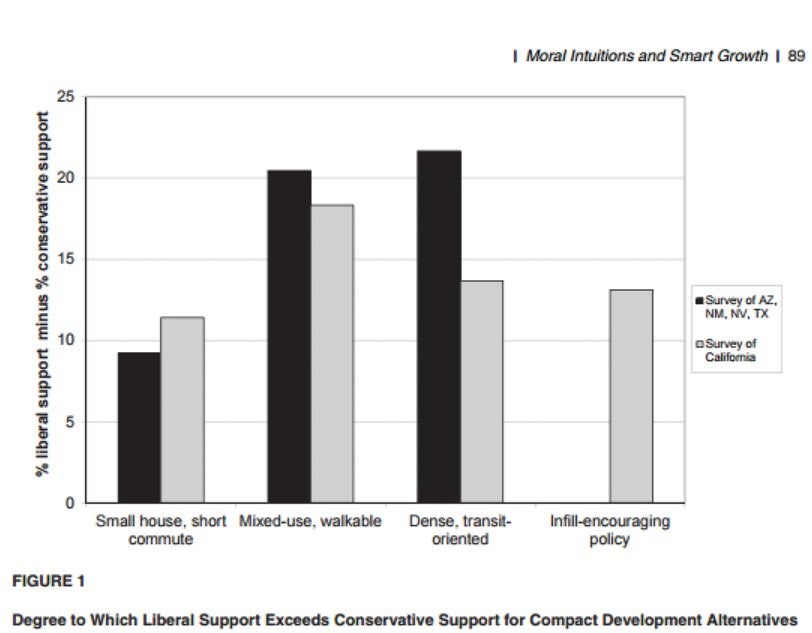

Yet studies have repeatedly shown the type of compact, urban development characteristic of smart growth is favored primarily by liberals, not conservatives.

Those studies, however, don’t offer a particularly good explanation for why that’s the case.

In his paper “Moral Intuitions and Smart Growth: Why do Liberals and Conservatives View Compact Development so Differently,” Arizona State University professor Paul G. Lewis draws on social psychology to propose another explanation: it’s all about gut-based, emotional responses.

It’s a Liberal Thing

If you follow each data point in the fight for urbanism – each dust-up at a neighborhood group over a new mixed-use project—it might not seem like liberals or conservatives are any more likely than the other to support smart growth.

But multiple studies confirm that liberals are more likely to support smart growth than conservatives.

In one of Lewis’ previous studies, survey respondents in Western states were asked for their preference in four potential trade-offs between urban and suburban development patterns. They answered questions like “would you rather have a small yard and a short commute, or a big yard and a long commute?” or “do you support policies that promote development in existing neighborhoods while preserving undeveloped land, or development on the fringes of urban areas to avoid density?”

Simply being conservative made people 10 percent less likely to supporting urban development. That’s true after controlling for other factors like race and income.

Other studies have shown the same patterns.

Studies have also shown that government policies like strict development regulations, government-backed mortgages and subsidized highways made the suburbs possible. Yet the suburbs are exactly what self-described opponents of government intervention say they prefer.

Similarly, liberals are more likely to say they support basic environmental protections. But Lewis’ previous study found caring about the environment doesn’t particularly correlate with supporting smart growth.

Instead of being explained by internally consistent ideology, the left-right split over smart growth is instead explained by deep-seated, subconscious emotions, Lewis’s paper argues.

It Comes from the Gut

Lewis explains the inability to attribute the left-right divide over smart growth to typical left-right values to an emerging field of social psychology called “social intuitionism.”

People don’t evaluate their preferences based on a coherent set of political beliefs, or from a core set of values, or by following cues from allies within the political fray.

Rather, decisions come from gut impressions.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt coined an approach within this view called “moral intuitionism,” suggesting that liberals and conservatives prioritize basic moral foundations differently. Liberals, he showed, were more likely to prioritize things like fairness and preventing harm to others; conservatives cared more about upholding traditional patterns or protecting themselves and their family.

Essentially, liberals and conservatives are predisposed to certain flash judgments that they don’t recognize, then they rationalize explanations for their views.

The moral intuitionism explanation suggests liberals prioritize an openness to experience, a need for stimulating environments and don’t care as much about preserving existing social structures.

Conservatives’ views are explained by vigilance against outside threats, identification with existing social norms and a concern with “purity.”

Lewis hypothesizes that you could use the moral intuitions that are typical of liberals and conservatives, respectively, to explain their feelings towards dense urban development.

Looking for Evidence

There hasn’t been a large-scale study to demonstrate a connection between moral intuitionism and views on urban development.

In its place, Lewis uses results from a survey of residents living in four southwestern states as a proxy for who is liberal and conservative, based on the tendencies moral intuitionism says are typical of liberals and conservatives, and the feelings of those individuals towards urbanism.

The survey asked respondents three questions on how they viewed trade-offs related to dense development.

It also asked a few questions that he used as a proxy for the foundations of moral intuitionism. For instance, it asked whether respondents felt a strong sense of “national belonging,” which he used as a stand-in for how much they identified with feelings of in-group loyalty, which moral intuitionism identifies with conservatism. He used questions on religious identification and anti-immigrant sentiment similarly.

Lewis found that individuals who said they don’t really feel a sense of national pride were much more likely to say they’d like living in a small house with a small yard if it meant having a shorter commute. They likewise preferred mixed-use neighborhoods where they can walk to stores.

People who weren’t particularly religious, meanwhile, were more likely to favor small houses and yards, mixed-use neighborhoods, and “high-density” living.

And people who say they’d happily pay more for groceries if it meant keeping immigrants out of the country were significantly more likely to want to have big yards and houses, and they weren’t as interested as others in living in mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods.

In all, he ran nine regressions on the relationship between individual preferences on development and the proxies for moral intuitions, and seven of them supported his hypothesis that people with conservative moral impulses are more likely to dislike the idea of urban living.

Ultimately, his study suggests some preliminary support for his idea that residents’ views on land use and development patterns aren’t ideological, they’re emotional.

And it could help explain why, despite the seemingly centrist appeal of smart growth – for liberals, social equity and environmental sustainability, for conservatives, economic opportunity and a less intrusive government – the urbanist movement has been disproportionately embraced by liberals.