This story was originally published on OffCite.

With the upcoming post-Harvey bond election, many people throughout the region are scrutinizing lists of potential flood mitigation projects and wondering if the published list would protect them from the next flooding event we all know is coming. Yet given the wide variety of challenges our region faces – such as issues related to economic development, affordable housing, public space access, equity, congestion, and threatened ecosystems – as well as limited public funding for addressing any and all of these challenges, it is crucial that we think of ways to leverage future public investment to address multiple challenges simultaneously to create a more resilient urban environment. Additionally, as I have argued before, the flood mitigation benefits these projects have on our region should not come at the expense of the livability. A highly engineered drainage channel might help reduce localized flooding, but its benefits could be overshadowed if it further divides already disconnected neighborhoods. It is therefore imperative that local decision makers move forward with projects that not only protect us from the next storm but address many of the other challenges our region faces at the same time to further improve the livability of the Houston area.

As they seek ideas for how to achieve these broader goals, local leaders might look to a design challenge that communities across the San Francisco Bay Area recently carried out. Modeled on the post-Sandy design competition, nine globally recognized, multidisciplinary design teams participated in the Resilient by Design challenge to develop long-term urban design strategies for nine communities across the Bay Area. Over an intense five-month period, the teams undertook deep-dive analyses of the fundamental challenges each community faced and developed long-term design solutions that addressed not only looming flooding threats but also many of the other fundamental challenges similar to the ones communities across our region face. Over a two-day period in mid-May, the teams presented their solutions and participated in roundtable discussions to engage with community stakeholders on how to continue the work of implementing the plans.

A stunning number of projects have been proposed by various government agencies since Harvey for the Houston region and we must ask how they will add up. Will the parts form a greater whole? The Resilient by Design challenge offers compelling lessons for producing comprehensive projects in resiliency that can simultaneously address environmental crises as well as challenges in socioeconomic and racial inequity.

The Estuary Commons masterplan proposal. Image courtesy of the All Bay Collective.

As with the post-Sandy design competition, the solutions the teams developed were intended to be replicable for communities across the Bay Area. However, unlike the post-Sandy competition, the Resilient by Design challenge had no dedicated disaster recovery funding attached to it. Therefore, participating teams not only had to develop transformational design solutions but also long-term funding strategies as part of their proposals. While some of the flooding threats that the Bay Area faces – namely encroaching high tides and rising sea levels – are different than the type we face from episodic torrential downpours, the proposals the teams envisioned as well as the strategies they developed for implementing them can serve as inspiration for integrated urban designs for our own region. The overall challenge process can also serve as an organizational framework for how we can develop the solutions that not only protect us from the next storm but increase the work to address the multiple core challenges our region faces.

Multiple Wins, Multiple Scales, and Multiple Timeframes

The design solutions that the nine project teams proposed spanned multiple scales and timeframes, some of which could be strategies that can be adapted to the Houston region. Some of the challenges the communities faced were quite similar to those we face, while others were quite different. For example, the proposed solutions for protecting low-lying buildings from flood inundation might have widespread application throughout our region, while strategies for facilitating additional sediment flows across watersheds might only have targeted benefits. Regardless, it is useful to analyze proposals to identify solutions that could work for our region.

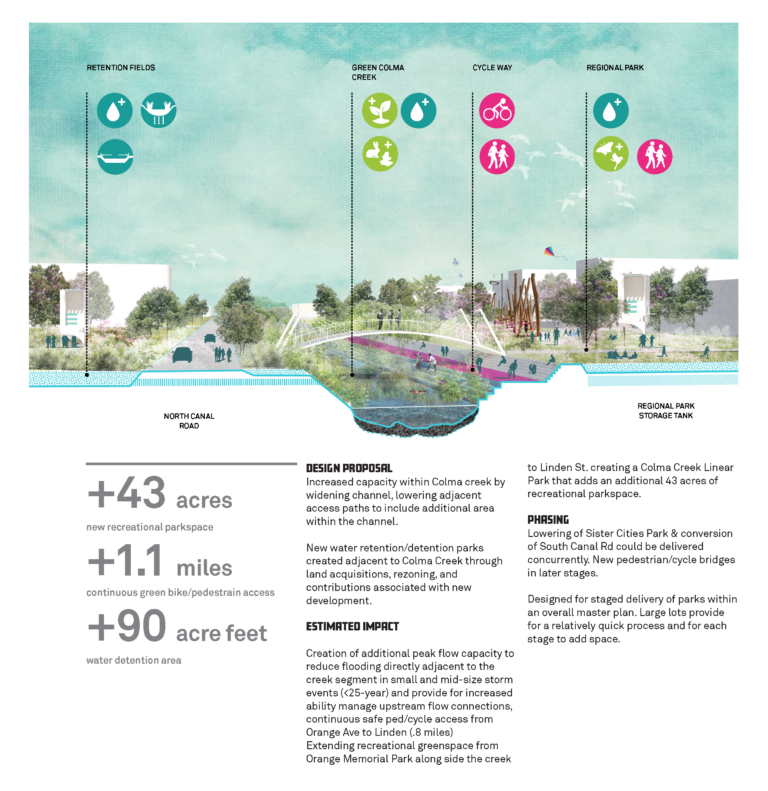

Colma Creek proposal. Image courtesy of Hassell+.

Some proposals actually include solutions that closely mimic efforts that we are already implementing across the Houston region. A number of teams recommended enhancing creeks, streams, and other waterways to better deal with flood mitigation while simultaneously transforming them into attractions and amenities for local residents, much like Buffalo Bayou Park and the Bayou Greenways initiative do in the Houston region. For example, as one of their key projects for South San Francisco, a team led by the design group Hassell proposed transforming Colma Creek into a linear greenway lined with continuous trails, playgrounds, outdoor theaters, and athletic fields, as well as a series of detention ponds. Their proposal not only aimed to solve key flooding issues, but also proposed a way to weave disconnected neighborhoods back together. As we imagine how to transform our bayous to further protect our city, it would prove useful to analyze the specific tactics the various teams proposed for adapting their waterways to both mitigate flooding and enhance the neighborhoods and communities.

Colma Creek proposal. Image courtesy of Hassell+.

Other proposals provide good models for how we can address very particular issues that certain parts of the Houston region face. For example, a team lead by TLS Landscape Architecture focused on what they dubbed the Grand Bayway, a large marshland area adjacent to San Pablo Bay in the northern part of San Francisco Bay. Situated between Vallejo and a number of small agricultural communities, the Grand Bayway plays a vital role as a flood protection buffer for the area and a natural habitat for countless species. It is also the location of a vital transportation corridor that links between eastern and western Bay Area communities. However, because of years of encroaching development and mismanagement of the resources that protect it, the marshland is under great threat as are the adjacent communities, farmland, and transportation links. Because of issues of subsidence and rising sea levels, there is a strong possibility that the marshlands as well as the key transportation links that cross it, could disappear forever.

Proposed Cullinan fishing camp on floating pontoons as part of the Grand Bayway Proposal. Image Courtesy of Common Ground.

Proposed Napa Junction Gateway as part of the Grand Bayway Proposal. Image Courtesy of Common Ground.

Therefore, it was vital to find solutions that ensure the Grand Bayway’s long-term viability and even existence. And yet, beyond the strategies the design team recommended to specifically restore the marshlands, reinforce the flood protections it provides to adjacent communities and farmlands, and reconstruct the vital transportation links, the TLS team also proposed transforming the region into a wetland version of Central Park for the Bay Area. Through a series of public amenities like fishing camps, boat launches, nature trails, and scenic overlooks, the team imagined taking what is currently a no man’s land and creating a regional destination where residents could more directly connect with the natural beauty of the Bay. Given how underappreciated resources like the Katy Prairie or large stretches of Galveston Bay play such a similar vital role in protecting our region, the methodology the TLS team used to devise its solutions for the Grand Bayway could be just as beneficial for both protecting us and creating our own regional natural destinations. The TLS proposal shows how the assets surrounding us that we are barely aware of can be transformed into critical flood protection measures as well as regional recreation destinations.

But the strategies that are most applicable for our region relate to challenges that are front and center in our collective consciousness. While the sharp memories of Harvey’s devastating flooding are acutely centered in many people’s minds, our region faces other challenges, such as increased congestion, escalating housing costs, threatened ecosystems, and widening inequality to name a few that threaten the social, economic, and environmental viability of our region. And many of the teams proposed strategies that worked to address a number of these challenges simultaneously.

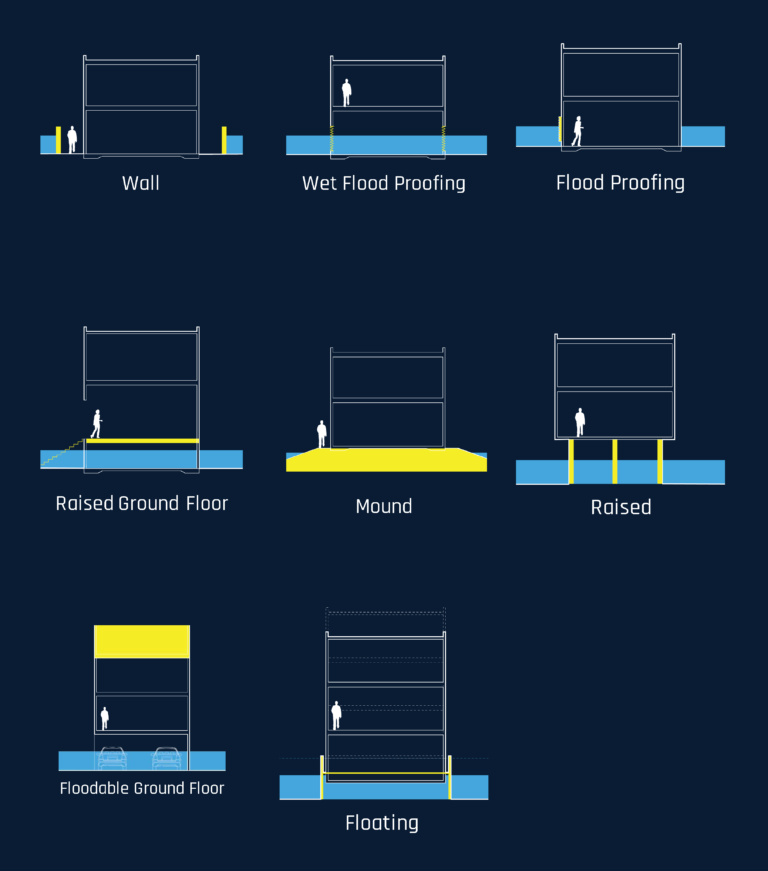

Proposed building upgrade strategies for the City of San Rafael. Image courtesy of Bionic Team.

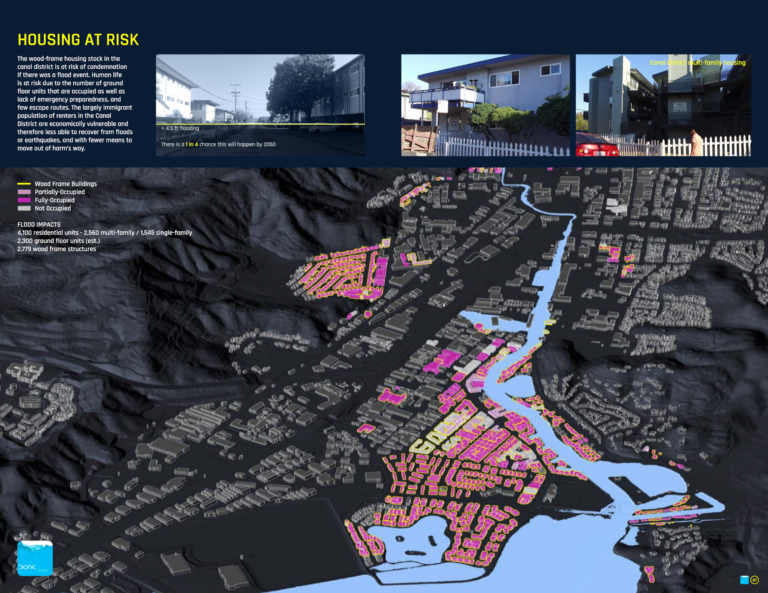

Given the astronomical costs of housing in the Bay Area, many teams focused attention on this pressing regional challenge. With much of the region’s residential units located in low-lying areas at risk from flooding, the problem will only get worse over time. Given the urban scale focus of the Resilient by Design challenge, the teams focused on broader housing strategies including policy recommendations rather than specific residential designs. For example, the team led by Bionic Landscape proposed changes to local construction ordinances for San Rafael, a city along the Bay that is particularly threatened by both sea level rise and flooding from storms. Much like previous policies throughout California requiring building renovation projects to include structural seismic upgrades, the team proposed a series of acceptable retrofitting strategies for dealing with flooding threats rather than a one-size-fits-all policy. Building owners could select the best solution – from retrofitting structures to allow ground floors to flood without significant damage to integrated flood barriers that prevent floodwaters from entering at all – that matched both the physical conditions of their structures as well as their budgets.

With the need for long-term housing development strategies to address both the threats of flooding as well as the acute affordable housing crisis, a number of teams proposed creating public land trusts. By separating the ownership of homes from the ownership of land, home ownership would be available to more people. And by identifying parcels at higher elevations within various communities and recommending modifications to local zoning requirements to allow for increased density, the teams also provided concrete strategies to provide affordable housing in areas that were better protected from flooding. With the complex interactions that affordability and flooding pose throughout the Houston area, having design teams comprehensively analyze the specific challenges we face and develop a variety of housing strategies that could be replicated across our region could have a tremendous impact for how we continue to thrive in the face of the perennial threat of flooding.

Yet the most compelling design strategy that virtually all teams incorporated into their proposals was targeted solutions that served multiple functions. Many proposed design solutions provided both protective measure for periodic threats as well as benefits and amenities the public could enjoy on an ongoing basis. As mentioned before, a number of teams proposed transforming waterways and flood control infrastructure into linear greenways and activity spaces that also linked disconnected neighborhoods together. Other ideas included developing a network of elevated bike paths along streets in San Rafael that also could be closed off to create a continuous dike to protect whole neighborhoods in flooding events. For the city of Richmond, a team lead by the interdisciplinary design firm Mithun proposed modifying the city’s shoreline to combine a multimodal parkway, freshwater treatment wetlands, levees, recreation trails, and tidal wetlands to both protect the city as well as provide a public amenity.

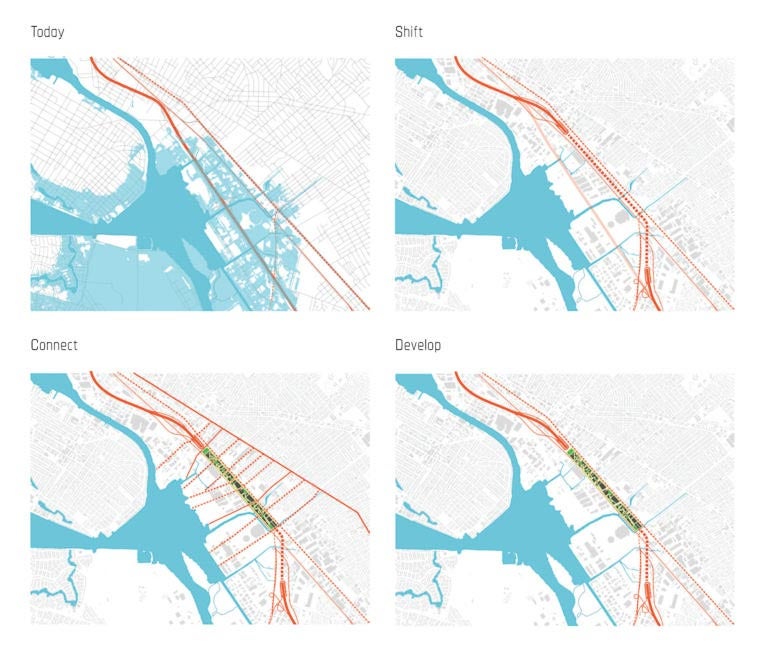

At a more macro scale, the teams also envisioned re-planning entire sections of cities to both protect vital infrastructure while spurring revitalization efforts. For example, the B+O+S team proposed transforming the site of a water treatment plant and its surroundings in the Islais Creek area of San Francisco into a living levee that includes wetlands to treat wastewater, urban farms for agricultural production, and sports and recreation facilities for surrounding communities. The All Bay Collective team proposed rerouting a major freeway in Oakland that is currently mere inches above the Bay to align with an existing BART, Amtrak, and Union Pacific Rail corridor and concentrate redevelopment efforts to create a highly connected and inclusive mixed-use district. And the team led by Field Operations imagined combining vast areas of wetlands, public parks, levees, and greenways with mixed-use, transit-oriented developments, to transform Moffett Field, an underutilized civil and military airfield adjacent to Silicon Valley, into a new community where natural and manmade environments would seamlessly intertwine. Ultimately, the teams demonstrated how thoughtful design interventions, from the simplest rain garden to full-scale transformations of entire districts, could protect communities as well as revitalize them.

Living levee at the South East Plant as part of the Islais Hyper-Creek Project. Image Courtesy of B+O+S.

Proposed I-880 realignment. Image courtesy of All Bay Collective.

Proposed transformation of Moffett Field. Image courtesy of the Field Operations Team.

The innovative plans, thought-provoking strategies, and seductive images suggested by these projects represent significant transformations of their respective communities. The analytical rigor that underpins the various recommendations outlined provide a compelling argument that the proposals are not just run-of-the-mill urban plans with pretty pictures meant to dazzle. Rather, they represent very strategic, long-term plans for both the concrete steps the respective communities can take today to start protecting themselves as well as the long-term visions that can guide those same communities for decades to come. By proposing discrete projects that have multiple benefits, the teams provided a blueprint for leveraging limited public funding to address multiple core challenges simultaneously. As we imagine similar transformations for our own region, such far reaching visions can help set an inspirational benchmark for our own planning efforts and shape the expectations we should demand from our local officials as they develop the long-term proposals that are intended to protect our own region. And by tackling multiple challenges that our region faces simultaneously, we could work to minimize the impact of future flooding AND address issues related to affordable housing, mobility, equity, and economic development while making our region more livable.

Rebuilding Trust, Cross-Agency Collaboration, and Data

And yet, undergoing the challenge itself yielded a number of indirect benefits that were just as if not more profound than the actual proposals themselves. As we continue to grapple with planning the appropriate and achievable infrastructure investments we need to protect our communities, the lessons learned that the teams presented should be considerations we take to heart as we continue moving forward after Harvey. Whether by sidestepping underlying structural challenges that underpin many planning efforts, pinpointing processes that yield more integrated results, identifying specific tactics that guide long-term strategy, or developing creative ways of effectively engaging communities in identifying the most fundamental challenges they face, the design teams shared ideas that not only yielded compelling design results but generated positive externalities that could enhance future planning projects.

A common theme that every team stated as a fundamental challenge was the need to build trust within communities. Whether because of chronic underinvestment, the inability to actually realize previous proposals, the feeling that community input is never incorporated into large-scale plans beyond a superficial level, that projects consistently fall short of established expectations, or even community engagement “meeting fatigue,” project teams consistently faced community members who expressed skepticism that anything meaningful would come from the overall process. One team described a community member who, at the beginning of the process, sarcastically declared, “You’re going to plan this for us again?” Therefore, many of the teams spent just as much time working to rebuild trust as on developing design solutions. As much as the process was an exercise in urban planning, it also provided a mechanism for mitigating deep-seated suspicion and for restoring the high degree of goodwill necessary for meaningful community engagement. In the end, a number of the teams stated that rebuilding community trust was one of the most significant results of the overall Resilient by Design exercise.

Another considerable benefit of the Resilient by Design challenge was the cross-agency coordination and cooperation that allowed the teams to develop thoroughly integrated, long-term visions. While we constantly hear of the need to break down institutional silos and develop cohesive, coordinated, and comprehensive solutions, such aspirations tend to be more of an ideal rather than an achievement. Often, there is never a single organization or team that is responsible for developing, documenting, and coordinating a cohesive, all-encompassing masterplan and vision. The Resilient by Design process acted as a neutral platform that allowed a wide assortment of constituents to not only sit at the same table to discuss the challenges they faced, but to also step into each other’s shoes to understand the disparate motivations that influenced their perspective. Many teams described how the structure of the challenge allowed a variety of stakeholders and public agencies to not only work together to solve the fundamental issues their regions faced but to come together to agree on what those fundamental challenges were. By creating a structured framework for working together, the teams were able to address issues like flooding, multimodal mobility, affordable housing, inclusive open space development, and even reknitting a frayed and torn urban fabric simultaneously through comprehensive integrated solutions. It would have been as though the Harris County Flood Control District; the City of Houston’s Planning, Public Works, and Housing and Community Development departments; METRO; TxDOT; and the Harris County Housing Authority worked side by side with community stakeholders and advocacy groups to develop integrated and comprehensive solutions that address the multiple fundamental challenges different areas within our region faces.

While members of a few teams openly criticized that certain voices – especially those of underrepresented communities – were absent from the early scoping of the overall Resilient by Design process itself and as well as the early phases of the actual planning efforts, team members seemed to universally acknowledge that cross-agency cooperation and coordination led to integrated solutions that reached far beyond than what would have resulted from separate and narrowly focused planning efforts. Without a structure to allow real cooperation to become a fundamental component of the planning process, governmental agencies and community organizations would have defaulted to focusing separately on the issues most important to their group.

Additionally, the neutral platform of the Resilient by Design challenge allowed metrics rather than subjective motivations to play a more central role in the decision-making process. As with any significant planning process, data collection and analysis were fundamental aspects of the work the teams performed. But because the Resilient by Design process was not driven by any particular stakeholder group or government agency – and by proxy that party’s agenda – the planning teams could present design solutions against the backdrop of a more expansive and inclusive set of social, economic, and environmental dimensions. This more encompassing set of metrics allowed the diverse constituencies, each with their own goals, to have more frank discussions about issues that may not have been brought up in a more narrowly constrained planning process. They could then collectively make the hard decisions of allocating limited resources based on a more mutual and comprehensive understanding of the underlying challenges that the data helped reveal. Ultimately, putting metrics at the heart of the process allowed for decisions that were more transparent and reflective of the needs and goals of a broader constituency.

Housing at risk in San Rafael. Image courtesy of the Bionic Team.

Given the years and likely decades necessary to achieve the proposed solutions and the lack of dedicated funding to carry out the plans, the teams also developed long-term phasing and implementation strategies that would also be applicable to our region. For example, as part of their analysis of the Islais Creek area, the B+O+S team reviewed numerous previous planning studies and masterplans that impacted their target area. Through that review, they were able to identify a number of projected long-term capital investments, such as a realignment of the Caltrain commuter line or the redevelopment of a regional wholesale produce market, planned for the region in the coming years. They then looked where those projected investments overlapped with areas communities identified as having strong opportunities for revitalization. The team then worked with both the community and public agencies to develop design solutions that incorporated both community and infrastructure investment goals to create a broader public benefit. By choosing locations that were already targets for long-term funding investments, the team was able increase the likelihood of having the projects realized by piggybacking on identified future redevelopment efforts. For a region grappling to finance all the infrastructure we know we need, such an implementation strategy would be critical for identifying potential projects that both protect us and enhance the livability of the Houston region.

One of the most significant external benefits of the Resilient by Design challenge, however, were the ways that the teams devised strategies for public engagement to rebuild the lost trust of communities. As one of the Resilient by Design jury members noted, “We cannot create cities for everyone, unless we’re first willing to listen to everyone.” Far beyond the typical one to two matter-of-course public engagement meetings that many public agencies have on their default project checklist, teams went far beyond just casually listening to constituents and devised a variety of public engagement campaigns that worked to both rebuild trust and allow community members to become true partners in the design process.

In some instances, picking the right team member to engage the public yielded activities that allowed a variety of communities to participate. The Exploratorium, the San Francisco science museum known for developing highly interactive exhibits and programs, and members of the Common Ground team developed an educational program for students that taught about different issues related to erosion, subsidence, detention, and wetland filtration as well as led a series of interactive nature walks through their target area so stakeholders could experience firsthand the on-the-ground conditions. As part of the All Bay Collective Team’s efforts for San Leandro Bay, art students from California College of the Arts developed “In It Together,” a board game that taught participants about the difficult tradeoffs designers and urban planners face when confronting real world constraints. By having a variety of community members play the game in different public forums, the team was better able to understand the needs of different stakeholder groups while community members better understood how constraints defined the possible choices that were available.

Students at Black Pine Circle School participating in building/testing hyper accretion garden models. Image courtesy of Common Ground.

For other teams, creating a strategy for where and when to engage the public was as important as how to engage it. In order to get feedback from residents of South San Francisco, the Hassell team used an unoccupied lobby of a former bank building at one of its downtown’s main intersections as their workspace during the challenge. The South City Shopfront was open to the public Monday through Friday to allow residents to provide feedback to the design team at their convenience. And by allowing the residents to hold their own community meetings in the space while the team was working there, team members could listen in on community conversations to identify the issues that mattered most to locals.

Community member providing input in the South City Storefront. Image courtesy of Hassell+.

Following a contrasting strategy, the Field Operations team decided to go to the community members where they were. With their project solutions focused on a series of wetlands, marshes, soft-shouldered creeks, and inter-tidal zones, they named their project the South Bay Sponge. In order to engage with the community, they created the Sponge Hub, a small Airstream trailer wrapped in environmental graphics to make it look like a giant sponge. By bringing their eye-catching Sponge Hub to festivals, sporting events, outdoor markets, and even busy urban corridors (and enticing people with edible cotton candy “sponges” once they were there), the design team was able to draw in a broad cross section of stakeholders and solicit a diverse set of ideas and opinions. Ultimately, looking beyond the default public engagement meeting for where and when to interact with the community allowed teams to collect more meaningful feedback. Such flexibility and resourcefulness would be just as beneficial as we look to develop resiliency solutions for our region.

The Sponge Hub. Image courtesy of the Field Operations Team.

But by far the most compelling public engagement strategy implemented by any team was to essentially flip the entire design process on its head. Rather than assuming the typical role of expert professionals who develop a plan for the community, the P+SET team actually empowered the community to develop the plan itself. As the foundational component of their process, they created an eight-week crash course for members of the community on the principles and strategies of permaculture, a design philosophy rooted in adapting patterns and systems observed in nature. Upon completing the course, community members took the tools they learned to assess their own community. Since they knew the needs and challenges their community faced far better than any group of outside professionals ever could, they were much better equipped to map out the locations of critical problems and then pinpoint the factors leading to those problems. They then worked hand in hand with the design team and local agencies to develop the “People’s Plan” which identified the low-impact development solutions that would address the problems they themselves had identified. Whether proposing restoring an existing orchard adjacent to a housing complex to help prevent erosion, locating key detention ponds and rain gardens to mitigate flooding on a critical street, or installing a diversion drain to reroute water around a frequently flooded community church, the community itself was at the center of analyzing the challenges threatening it and devising the solutions that would help solve those problems. Giving residents of the Houston region similar tools to become more active participants in solving the challenges we face would not only lead to much better conceived solutions, it would motivate community members to push civic leaders to carry out the plans that they themselves helped craft.

Participants and instructors of the permaculture course held in Marin City. Image courtesy of P+SET.

Addressing Core Challenges

Ultimately, though, the most profound aspect of the Resilient by Design Challenge was how these indirect benefits combined to allow the communities to more acutely identify the most fundamental underlying challenges communities face and develop aspirational visions for tackling those challenges. The combination of these benefits – intense community engagement to rebuild trust, a neutral platform where serious issues could be candidly discussed, and a set of comprehensive social, economic, and environmental metrics that led to a more transparent decision-making process – allowed civic leaders, government officials, and community stakeholders to look beyond problems that are merely symptoms of more core challenges and address the core issues directly.

By creating an environment where those core challenges – such as underinvestment in infrastructure due to fiscal constraints, gentrification and displacement, or the real impact of compromised ecosystem services – could honestly be discussed and debated, the Resilient by Design framework created a more pivotal and essential starting point for designs to spring out of. Design teams could use this starting point as a much stronger foundation when devising solutions that could have the greatest possible impact. As Stephen Engblom, AECOM’s Global Cities Director, who was the project director for the All Bay Collective team and an alum of Rice Architecture, described: “The magic of the Resilient by Design process was the opportunity to tackle projects that aren’t happening but should be happening.” As an example of how the process led to more frank conversations about deep rooted challenges, his team developed a quadruple bottom line calculator for the San Leandro Bay site that will be used by key stakeholders going forward to objectively evaluate set performance indicators of future planning proposals. The four indicators, based on equity, economic, environmental, and governance domains, are set by the stakeholders themselves and will help all stakeholders more transparently devise solutions that provide the largest benefit to the broadest constituency. By focusing on these core challenges that have ramifications that are simultaneously social, economic, political, and physical in nature, design teams could go beyond addressing problems that were merely symptoms of larger issues and develop solutions that could have both broad and deep impacts on their target communities.

The Resilient by Design process should in no way be considered perfect. The fact that there was no actual funding earmarked for the proposed projects meant that their ultimate implementation is uncertain. Many teams criticized the fact that underserved communities did not have a seat at the table as the scope of the overall process was developed and during the initial project planning phases. Additionally, the costs of managing a large-scale design challenge and planning effort AND providing nine large, multidisciplinary design teams fair compensation for work they undertook in a four-and-a-half-month period would likely be much higher than the roughly $5 million Resilient by Design budget. If we were to bring a comprehensive planning process like Resilient by Design to Houston, we would have to address these and other areas of potential improvement.

And yet, the Resilient by Design challenge provides an intriguing model to study as we look to plan long-term solutions to address the challenges the Houston region faces. The deep level of analysis, the frank conversations about core community challenges, the high level of community engagement and project buy-in, and the thoughtful, well integrated, and comprehensive design proposals provide a compelling argument for adapting a similar planning process for the Houston region. Given the variety of scales the solutions propose, such a process might also help spur a much-needed conversation about the balance between large-scale engineered solutions and smaller-scale localized green infrastructure efforts that could be more dispersed across the region and enhance its overall livability. And design solutions that address multiple challenges simultaneously can help leverage limited public funding, so projects can have a broader and more profound impact in our communities.

Much of the Houston community is still struggling to recover from Harvey and likely will for years to come. Local resources should still be focused on those with the greatest needs and limited ability to recover from such a devastating catastrophe. Yet looming threats also weigh on the collective consciousness of everyone in the region. When we get to the point of transitioning from recovery and rebuilding to looking to better protect ourselves in the future, structuring the planning process to guide us to the best possible version of that future is crucial. The Resilient by Design challenge offers a compelling model for developing the types of transformative projects that we will likely need to address the core challenges our region faces while simultaneously making it a more livable home for both current and future Houstonians. And just as importantly, the visionary proposals such an inclusive and comprehensive planning process could imagine would also give Houstonians something that is currently in short supply in our collective psyche: hope for a better future.

José Solís is Founder of Big and Bright Strategies and Project Manager with the Buffalo Bayou Partnership.