New research from Rice University sociologists shows the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) program that funds the voluntary buyout of flood-prone homes disproportionately targets counties and neighborhoods with whiter populations. It’s the first nationwide study to focus specifically on racial disparities in the buyout program.

As climate change continues to raise sea levels that threaten large coastal cities, it also impacts areas farther inland with extreme weather events that dump massive amounts of rain that overwhelm rivers and other tributaries such as bayous. In turn, flooding frequency has been ratcheted up in urban areas such as Houston, New Orleans, Washington D.C. and New York. Add to that the ongoing expansion of flood plains because of climate change and an estimated 41 million people in the United States live in areas at risk of flooding.

The Houston metropolitan area has been hit by six flooding events in five years that were declared disasters by the federal government. According to the Harris County Flood Control District (HCFCD), more than 150,000 homes flooded during Hurricane Harvey. Many of those were located outside of the 100-year flood plain.

Inequities in FEMA’s long, complex process of home buyouts

The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) has been used in more than 500 cities and towns in every state except Hawaii as a way to address the need to relocate those who live in areas that flood. In short, using funds from the FEMA program, local governments purchase residential properties, which are razed and left as green space. That may sound simple but it’s a long and complicated process.

“After a flood, it’s up to the local flood control district to submit a buyout proposal to FEMA if they want to help homeowners sell their properties and move away from their flood-prone homes,” said lead author Jim Elliott, chair of Sociology at Rice and a fellow at the Kinder Institute for Urban Research. “As this process unfolds, some neighborhoods are selected over others. And some people accept the buyouts, and others don’t. We wanted to look at all of this over time to see how it might link to racial privilege, net of local flood impacts.”

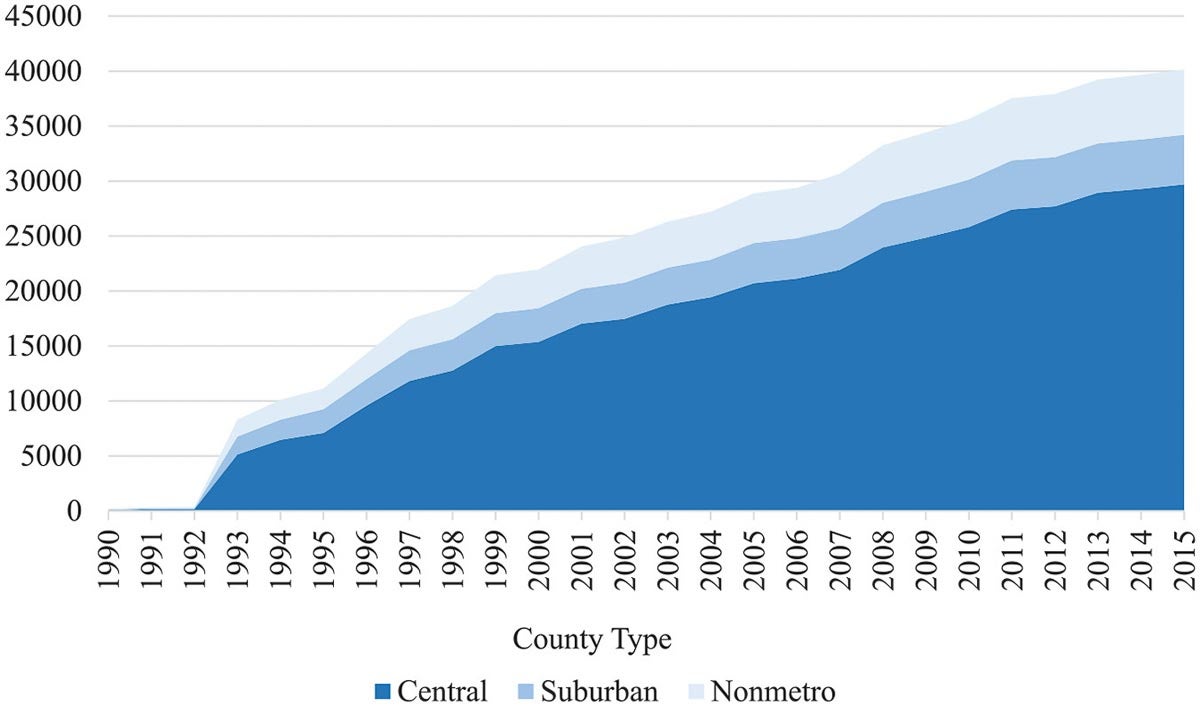

This graph shows the cumulative number of FEMA-funded buyouts in central, suburban and nonmetropolitan counties of the United States from 1990 to 2015.

Source: Author calculations

With Congressional approval of the HMGP in 1985, local flood districts — in Houston’s case, the Harris County Flood Control District — could apply for funding to buy properties at high risk of flooding. If funded, property owners could then either accept or reject the buyout offer. The program was used mostly in rural areas until 2000 when it became “a go-to tool for local governments everywhere looking to plan for future flood risks.” Since then, the program has evolved into an urban buyout program in which 75% of completed transactions have taken place in counties at the center of metropolitan areas, according to the study published online Feb. 12 in the journal Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World.

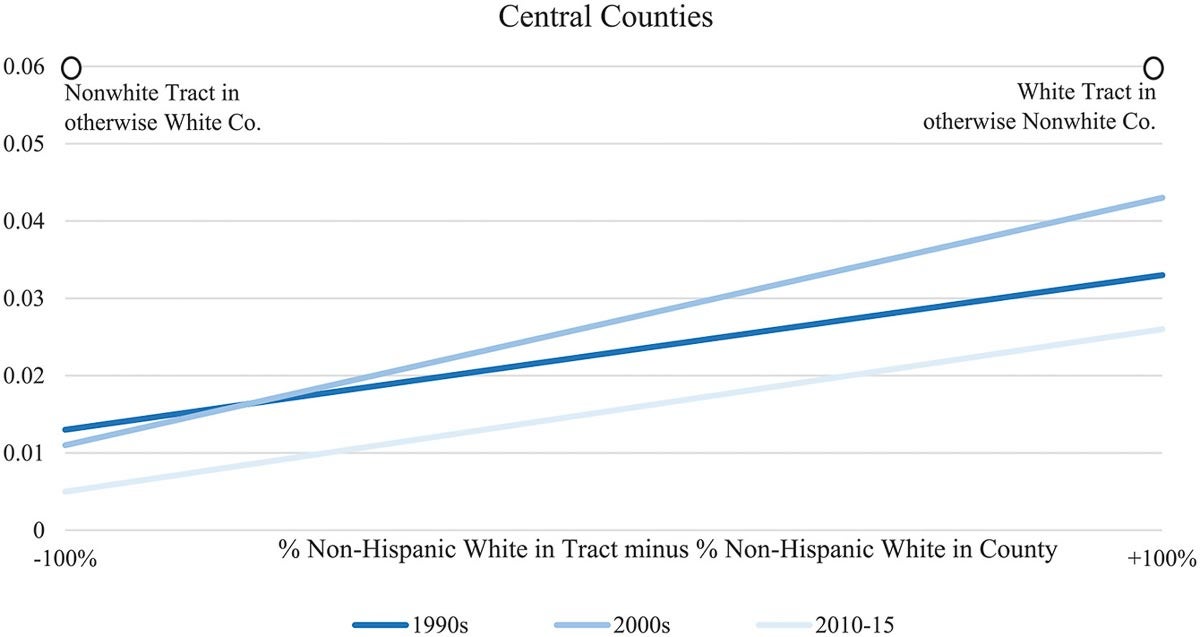

And among central counties, the study shows, racial composition was an indicator of where buyouts occur. “It starts with whiter central counties and relatively whiter neighborhoods within those counties being more likely to gain access to federal buyout assistance. It ends with homeowners in neighborhoods of color being more likely to accept that assistance, making nonwhite neighborhoods in otherwise white counties the areas of greatest demolition, statistically,” Elliott and his co-authors report. Tellingly, these racial disparities were evident only in central counties of metropolitan areas, not in suburban or nonmetropolitan counties.

Racial bias in fed’s successive attempts to intervene

Because the program is becoming crucial to how the federal and local governments address climate adaptation, a “social scientific investigation” was merited, said the researchers, who conducted a series of statistical analyses on more than 40,000 FEMA-backed buyouts from across the country in the 25 years between 1990 and 2015.

Despite its intentions, there’s little doubt the federal government’s latest efforts at flood mitigation have difficulty avoiding racial bias. That’s because, “when housing is the ultimate target, such bias can be difficult to suppress, especially in urban areas” where property prices and diversity typically are higher than in nonmetropolitan areas.

This is true for several reasons. Cities have more people and money than small towns and rural areas, which gives those city and county governments more resources and deeper pockets to pursue federally funded buyouts. “It is also because cities have neighborhoods forged through long histories of racial segregation that live on to create unequal access to opportunities in good times and bad, as well as in ways that can accumulate across multiple steps of housing transactions, even when the buyer is a government agency.”

This graph shows the predicted probability of a census tract participating in a FEMA-funded buyout program by the proportion of (non-Hispanic) white residents relative to the county, by decade for central counties only.

Source: Regression results for central counties reported in Table 2, with all other variables set to their mean values.

Researchers examined county and neighborhood data

To learn if the FEMA buyout program disproportionately focused on urban areas, the researchers categorized counties as central, suburban and nonmetropolitan — according to the Office of Management and Budget’s 2015 designations.

From there, they drilled down to the census tract level to find the likelihood that a neighborhood would participate in the federal buyout program. They used the 2010 census tract boundaries to determine neighborhood demographics.

To measure the racial composition of a neighborhood, the researchers took the proportion of white residents in a census tract and subtracted the proportion of white residents in the surrounding county.

Different results in Kashmere Gardens and the Northeast

Elliott and the study’s co-authors — Kevin Loughran, a postdoctoral fellow, and Phylicia Lee Brown, a Ph.D. fellow — point out that the outcomes of the buyout program were different in New York and New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy and in Kashmere Gardens, a historically black neighborhood in Houston. In both cases, residents united against two threats to their communities: flooding and gentrification.

In Staten Island and areas along the Jersey shore, white working- and middle-class residents lobbied for the buyouts of entire communities following Hurricane Sandy. The mass buyouts allowed the homeowners to “hand their community back to nature rather than to wealthy newcomers.” While in Kashmere Gardens, residents and community leaders unified in opposition to buyout offers they viewed as a modern-day urban renewal effort to remove black residents from their neighborhoods.