This post was originally published in the Houston Chronicle.

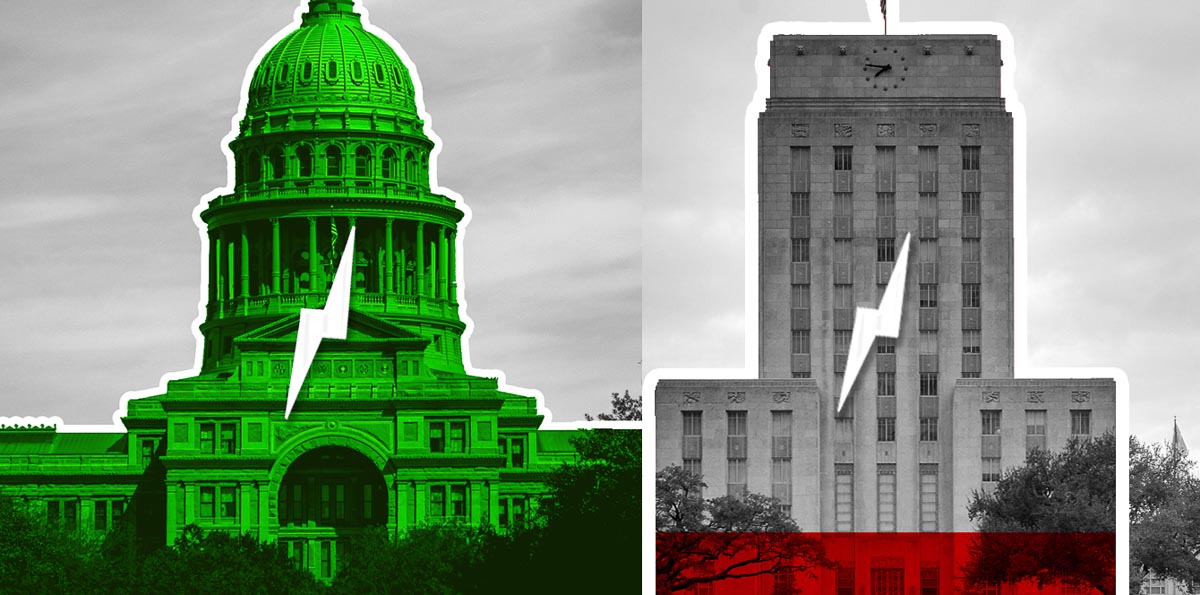

As momentum in Austin builds against cities and counties, Texas’ local governments are being squeezed from both ends. On one hand, state officials have repeatedly tried to strip locals’ capacity to address their own problems — lawmakers have stopped cities from requiring certain background checks for Uber drivers, setting their own property tax rates or even establishing rules for where fracking can occur. On the other, as cities fight back in Austin, there are increasing calls for lawmakers to make it illegal for cities or counties to lobby at all.

But as a House investigative committee begins looking into comments made last session by Speaker Dennis Bonnen about his intentions to make 2019 “the worst session in the history of the legislature for cities and counties,” the momentum could be changing. In fact, it could be a transformational moment — one in which the state and its local governments can sort out what the proper role of cities and counties should be, and determine once and for all how local governments can be partners in governing.

Meanwhile, local officials are firing back. The Texas Municipal League called it “shocking to hear a state official express such animosity toward the cities and counties in his own state.” And in a recent Houston Chronicle Opinion piece, my Kinder Institute colleague Ed Emmett — a former Harris County judge and a former state representative from Harris County — called Bonnen’s comments “disgusting.”

The importance of a local and state partnership

Local governments lobby in Austin — as they do in virtually every state capital in the United States — because they have to. The laws and the funding sources that affect their constituents usually originate at the state level. As the country has become more politically polarized, state legislatures have become more ideological — both on the right and on the left — and states have begun to impose their will on local governments more frequently.

Of course, states have a significant advantage in this power struggle because under the United States Constitution they are sovereign. As I always remind my students, don’t ever forget the name of our country. It’s not the United Cities, Counties and Municipal Utility Districts of America. It’s the United States of America. States inherently have the upper hand.

Indeed, local governments exist because states have created a system allowing — and in some cases requiring — them to exist. And most states create the system in the same way. Counties are subdivisions of the state, designed primarily to deliver state services such as indigent health care and criminal justice. Cities are created by local residents to provide a wide range of additional services, from public works to parks, often with a higher property tax rate. Municipal utility districts provide utility-related services, such as water, sewage and drainage, to certain areas, and usually with a higher property tax rate as well.

The power of strong local governments

Having strong local governments makes sense in many ways. They can focus on local needs in a responsive way that the state simply cannot. Does anybody in Austin want to have to decide how many parking spaces a new office building or condo tower in the Galleria has to provide in order to get its permits? And not surprisingly, people tend to trust their local government — the one closest to them — more than state and federal governments.

Ideally, local governments are true partners in governing with the state. They are given broad powers by the state, as well as the freedom to use those powers as they see fit in order to serve the needs of their constituents. But for the state, it’s always tempting to strip local governments of power and, in the process, strip them of the ability to be true partners in governing.

Something like this happened in California with the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978 — a tale that has important lessons for Texas.

Placing limits on property tax revenue

As with Texas today, the problem in California was that no one was fully accountable for the local property tax bill. Cities, counties, school districts and special districts all imposed their own taxes and the rates went up — to 2%, 2.5%, 3% of assessed value and beyond. So, when California’s first big runup in housing prices came along, voters endorsed Proposition 13 — an extreme measure that capped property taxes at 1% of assessed value.

But the initiative also placed responsibility for divvying up the resulting tax revenue with the state legislature. Overnight, cities and counties were transformed from partners in governing to mere vassals of the state government. Instead of levying their own tax rates, they were competing with other taxing entities for a fixed pool of property tax revenue. Out of necessity, they had to start lobbying in Sacramento for their piece of the pie. Not surprisingly, this created hostility between Sacramento and locals that has lasted to this very day.

Last year in Texas, the legislature adopted a limit on increases in property tax revenue. It’s no Proposition 13 but it does restrict the ability of local governments to raise revenue.

Side effects of a ban on lobbying

From the point of view of conservative legislators in Texas, this move protects taxpayers from the whims of profligate local politicians. But from the point of view of local government — whether those officeholders are Democratic or Republican — this new law reinforces the need for lobbying in Austin. If the state is going to box cities and counties in, isn’t it only fair that local elected officials have the ability to make their case to the legislators?

If local governments can’t lobby Austin, there’ll almost certainly be some adverse side effects. Other interests — primarily business interests — will continue lobbying to restrict local power in ways that benefit their business. In response, the locals will try to find other ways to lobby. For example, they may have to rely on private entities such as Chambers of Commerce that may or may not truly represent their constituents. Or they may create other nonprofit entities to do the lobbying — but those entities will have to raise money from business interests and others to avoid using tax funds.

While it’s true no taxpayer funds would be used to lobby, there’ll be no guarantee that the interests of local residents will be front and center in this new lobbying environment.

Local governments need to be given an option

At least to me, the choice seems clear. Yes, the state can prohibit local governments from lobbying — so long as the state also eliminates the reason for lobbying by giving cities and counties more power. Or the state can accumulate more power in Austin, but let local governments lobby the legislature for what they need.

Our state leaders probably don’t want to face this choice directly. But both local officials and state legislators who care about their constituents should try to force this choice. The state shouldn’t take power away from local governments and then prohibit them from lobbying to get that power back. Otherwise, why have local governments at all? That approach destroys the idea that the state and local governments are true partners and robs local residents of a voice in the process of governing.