Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt of material from West Side Rising: How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement, now available via Trinity University Press.

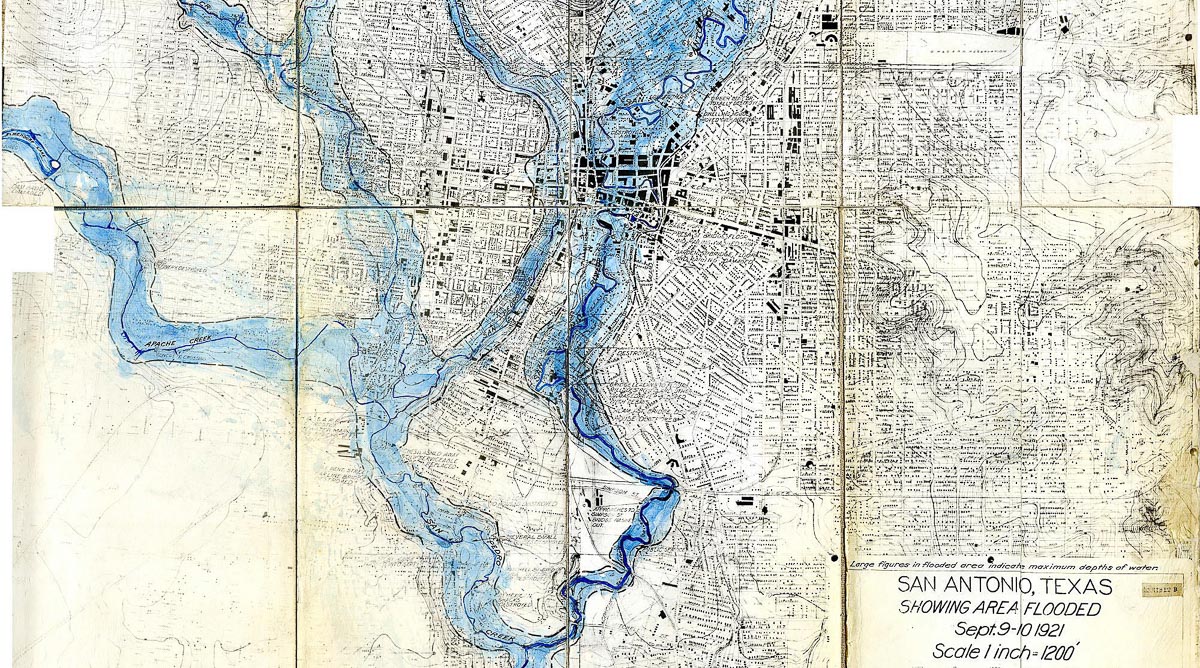

It was 1921. The flood had begun on the evening of Friday, Sept. 9, with heavy rain lashing the San Antonio River watershed; by 10 p.m. Saint Mary’s Street, a major north-south thoroughfare through the center of the city, had become a river.

San Antonio went underwater. So did New Braunfels, San Marcos, and Austin, along with the smaller communities of Taylor and Thrall. Each scouring event profoundly altered the communities. In this instance, the staggering volume of water that came crashing down when the storm broke was the result of a slow-moving tropical depression that several days earlier had crashed ashore in northern Mexico. As it spun over the Rio Grande, the system dumped upward of 6 inches on Laredo, submerging low-lying neighborhoods. Pressing north, it cycled along the Balcones Escarpment, where storm cells unleashed their full fury. Thrall, in Williamson County, recorded an eye-popping 38.21 inches in a 24-hour period, in what was believed to be one of the largest single-day rainfall events in the continental United States. More than 23 inches fell on Taylor, and Austin got 18.23.

Property damage was severe, but the number of fatalities was even more so: in Taylor, 87 people died, and another six perished in its surrounding county of Williamson. Six people drowned in Travis County. By all measures, the 1921 flood was the most devastating in the history of the Lone Star State.

Nowhere was this truer than in San Antonio, a city whose 18th-century Spanish planners had platted in a floodplain so that its streets, plazas, and residential areas lay within the embrace of two waterways, the San Antonio River on the east and San Pedro Creek to the west. It was no stranger to floods: There had been devastating events in 1819, 1845, and 1865, as well as 1913 and 1914.

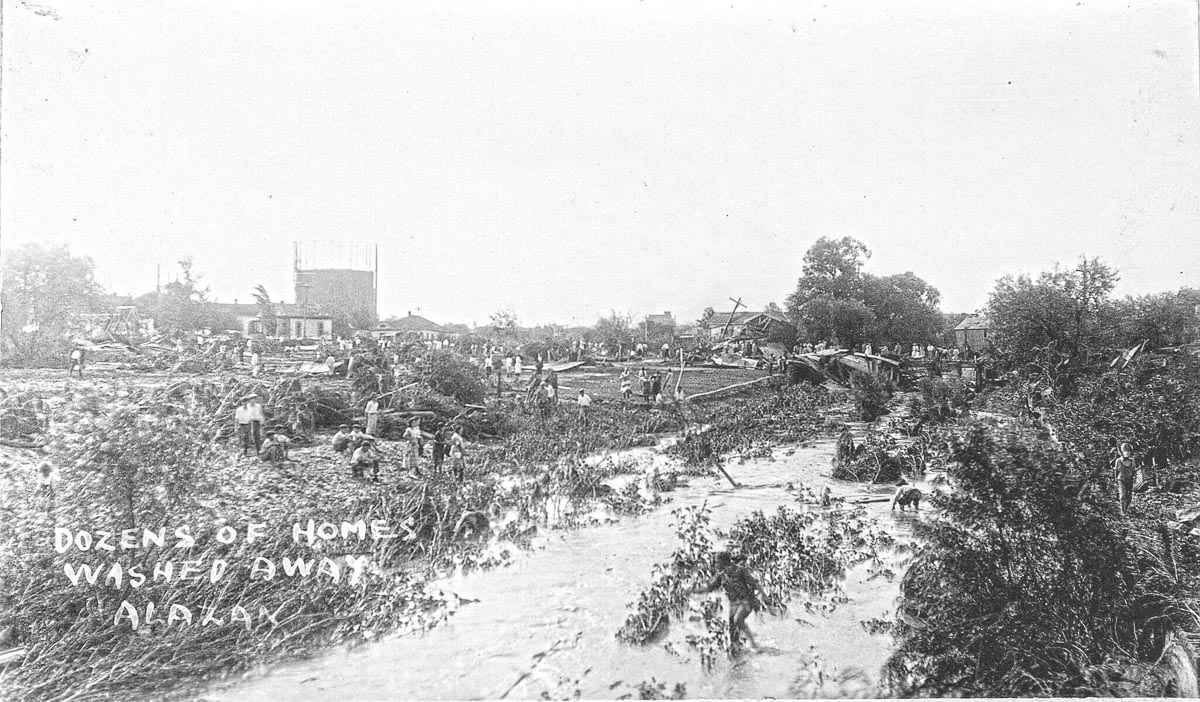

The vast majority of those who perished in 1921 were on the city’s densely populated West Side, in an area known locally as the corral or jacal district (so named for the huts and shacks many of its residents occupied). These rough shelters were no match for the powerful floodwaters that raced down the West Side’s interlacing of creeks—the Alazán, Martínez, Zarzamora, Apache, and San Pedro. That evening, the Alazán proved the deadliest.

“The total number of lives lost will never be known,” wrote US Geological Survey water engineer C. E. Ellsworth in an extensive analysis of the impact of the 1921 flood across central Texas, “but the best estimates available indicate that at least 224 people were drowned, most of whom were Mexicans who lived in poorly constructed houses, built along the low banks of the streams.”

This disparity in the demographics and distribution of death in San Antonio dovetails with a statewide pattern with regard to the disaster: spatial inequities, ethnic discrimination, and environmental injustices determined who survived and who died in this massive flood.

Courtesy Trinity University Press

Since the 1850s, the West Side had housed the city’s poorest residents who lived in substandard housing and experienced frequent outbreaks of tuberculosis, yellow fever, and other diseases. It was not an accident, then, that the September 1921 flood was especially lethal and catastrophic for those who were geographically marginalized.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, one women-led mutual aid group, Cruz Azul Mexicana (Blue Cross of Mexico), began serving the flood’s survivors, providing meals, clothing and other resources—hours in advance of the American Red Cross. Without diminishing the laudable contributions of the US Army and the Red Cross to West Side residents, Cruz Azul’s grassroots efforts had the distinct advantage of being homegrown and hands-on. (Cruz Azul would eventually coordinate with the Red Cross amid the recovery.)

To feed and clothe the displaced, Cruz Azul initially gathered much needed supplies from West Side merchants and storekeepers, as well as from fraternal mutualista organizations. Though it was separate from the Cruz Azul organization in Mexico, the San Antonio chapter did accept a $2,000 donation from the Mexican government, allowing it to feed hundreds of people and provide medical care at two relief sites.

Even though it was centrally focused on the needs of the city’s West Side, this “grupo de senoritas” expanded its charitable outreach far beyond, serving nearby communities. A year later, the San Antonio chapter hosted the first binational conference of Cruz Azul affiliates in 1922, and in the succeeding years women-dominated sister chapters proliferated across the country. Historian Julie Leininger Pycior suggests that “Cruz Azul Mexicana may well have been the first nationwide Latina organization in the history of the United States.”

Meanwhile, using their manifold resources, the city’s commissioners and the flood prevention committee, the latter of which consisted of major downtown property owners and leading engineers, developed a political consensus around the pressing need for a dam and other related flood control infrastructure to protect the business district’s property values and boost the urban economy. The Olmos Dam in late 1926 was an historic accomplishment, yet as is so often the case in human affairs, nothing is ever quite what it seems.

With a dam to its north and a straightened, deeper, and wider river running south, San Antonio’s downtown boomed. The West Side did not. True, there had been modest investments in several of its creeks. The confluences of the Alazán and San Pedro, and the San Pedro and San Antonio River appear to have been restructured to carry greater volumes of water; some of the creek beds would be cleared of vegetation. None of these improvements, though, offered the kind of economic stimulus that elsewhere increased the property values and assets of the city’s downtown merchants and landlords.

After New Deal programs in the 1930s began to offset the need for mutual aid groups, Cruz Azul began to fade. But eventually, the next generation of organizers began stepping forward, taking advantage of new civil rights laws and expanded federal influence in urban life. Communities Organized for Public Service (COPS), a powerful parish-based, female-dominated grassroots organization, burst into local and national prominence following a relatively modest 1974 flood along Zarzamora Creek that turned streets into rivers and swamped houses.

Tired of suffering from this form of slow violence and the political disregard that led to it, activists challenged the city to finally act on behalf of flood-weary neighborhoods. Their very public challenge developed into the organization’s remarkably successful initiative that relatively quickly transformed the city’s political structure, its budgetary commitments, and the health and resilience of the West Side community. Its activists later transplanted COPS’s organizing methods and galvanizing message to Los Angeles, Houston, and other major US cities, making it one of the country’s first political movements dedicated to environmental justice.

The overarching goal of “West Side Rising” is to bring the history of the 1921 flood to life. It makes extensive use of a constellation of primary and secondary sources, including correspondence, government documents and photographs, oral histories, and newspaper accounts, as well as scholarly analyses of this and other floods, to establish a wider context to understand what happened in San Antonio. Many of these documents have been overlooked and are, as a result, all the more riveting. What they and other sources make clear is that this disaster, like so many others, was not “natural,” a calamity beyond human imagining and control. Quite the opposite.

Char Miller, formerly a professor of history at Trinity University, is the W.M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis at Pomona College. He is the author of the "Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism", "Deep in the Heart of San Antonio: Land and Life in South Texas," and "Public Lands/Public Debates: A Century of Controversy."

The views, information or opinions expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research.