Between 1993 and 2013, there were only four counties in the entire country that did not experience significant damage from some sort of natural hazards, like flooding, earthquakes or tornadoes. But, argue sociologists Junia Howell and James Elliott, while the reach and growth of these hazard-related damages are concerning, "so too are the social inequalities they can leave in their wake."

In the latest publication from the pair looking at the connection between wealth inequality and disaster, the researchers used county-level data from across the country, combined with data from some 3,400 households across the country, to simulate the differences in wealth accumulation between white and black households over the 10-year study period. As many advocates familiar with the uneven trajectory of disaster recovery can attest, experiencing a natural hazard seemed to increase inequality. In fact, the study published in Socius found that "the more natural hazard damages accrue in a county, the more wealth white residents tend to accumulate, all else equal." At the same time, the scholars found that black residents "tend to lose wealth as local hazard damages increase."

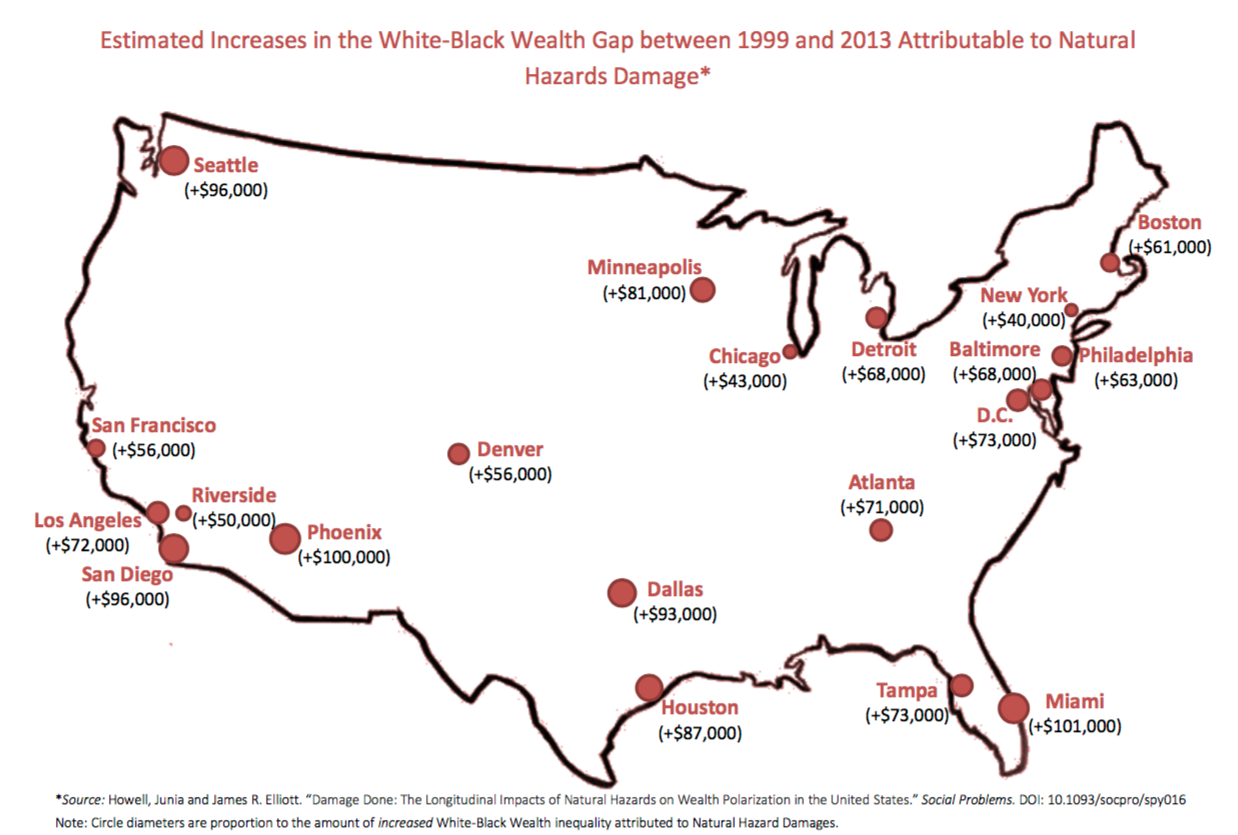

The findings underscore previous research by Howell, a Kinder Scholar and assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, and Elliott, a Kinder Fellow and professor and sociology department chair at Rice University. In an August study published in Social Problems, the pair found that white residents who lived in counties that had at least $10 billion in hazard-related damages between 1993 and 2013 accumulated an average of $126,000, while black, Latino and Asian residents lost an average of $27,000, $29,000 and $10,000, respectively, in those same counties. In short, more disasters seem to produce more wealth inequality. In Houston's Harris County, the average black-white wealth gap over the study period was $87,000.

Source: Junia Howell and James Elliott. “Damage Done: The Longitudinal Impacts of Natural Hazards on Wealth Polarization in the United States.”

What drives the increase in inequality? Most likely, a number of factors, including "differential access to government assistance, differential disruption to housing and income, and unequal opportunities to tap into substantial flows of recovery capital that stream into damaged areas," according to the Socius study. In fact, the pair found counties receiving more Federal Emergency Management Agency assistance had even larger white-black wealth gaps. "In other words, how federal assistance is currently administered seems to be exacerbating rather than ameliorating wealth inequality that unfold after costly natural hazards."

In the August article, the researchers reflected on some of the reasons why assistance programs might have such different impacts for different groups:

For example, more privileged residents and property owners may gain access to new resources and opportunities that include new business prospects supported by federal recovery investments; low-interest loans; significant payouts from public and private insurance policies; and, opportunities to transfer wealth to adult children through sharing of financial windfalls or property restoration and investment. By contrast, for less privileged residents and non-property owners, local damages are more likely to trigger financial liabilities as a result of experiencing an increased likelihood of losing one’s job; having to move; paying higher rents due to reduced housing stock; and, dipping into already meager savings to compensate for such expenses. In some cases, government recovery programs have even suspended legal protections for low-wage workers to speed up recovery and get local economies “going again.”

With roughly $1 billion in federal housing assistance allotted both the city and the county each after Harvey, Houston finds itself at risk of perpetuating this pattern of inequality. Already, an analysis shows that individual FEMA payouts tend to favor homeowners over renters and researchers have found that between 1985 and 2017 before Harvey, buyouts in Harris County have tended to fuel white flight.

Though the latest findings offer a high-level take on the relationship between disaster and inequality, the study's message is clear: "[T]wo major challenges of our age—how we respond to rising wealth inequality and how we respond to rising disaster costs are connected."