The past two Kinder Institute Forums turned out to be bookend presentations on the power and importance of public spaces and the great need to invest, renew and care for these vital pieces of the social fabric in America.

In December, sociologist Eric Klinenberg talked about public libraries and churches as the social infrastructure connecting residents in many communities. His research has shown that neighborhoods and communities flourish or flounder depending on the strength of their social infrastructure.

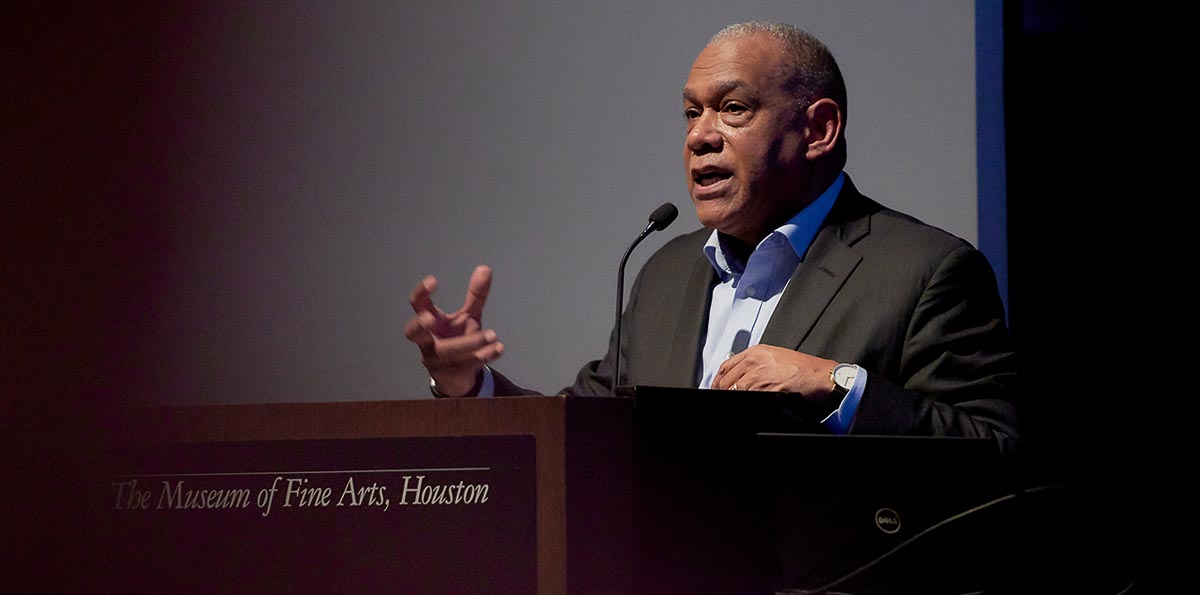

And on Wednesday night, New York City Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver discussed the many benefits of parks and public spaces — from improving mental and physical health to making a city more resilient and even lowering crime rates — in his presentation “The Future of Parks and Public Space: What’s Next?”

Both spoke to the enormous potential of public places and spaces to improve lives and serve the common good — but to do so there needs to be equity in quality and access.

Equity equals fairness

When landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, along with his partner Calvert Vaux, designed New York’s Central Park, he insisted it be a common green space with equal access to everyone. Today, this seems like a very basic principle of public parks but that wasn’t the case in 19th century New York.

“But what was different about Olmsted is he wanted [parks] to be accessible for all people,” Silver said. “Regardless of your income, your economic status, he wanted public spaces that were welcome to all. Democratic public spaces.”

Silver described how the city’s parks department spent roughly $5.7 billion on capital improvements in the past 20 years on a 30,000-acre park system comprising nearly 2,000 parks. However, 215 of those parks received what Silver called “little to no investment” — less than $250,000 over two decades.

“Seniors, children, families — while they saw other parks getting redeveloped, theirs remained unchanged,” he said. “Twenty years — from kindergarten to college — no change whatsoever. That’s. Not. Fair. And we have to change it.”

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio invested $318 million in capital funds to transform 67 parks through the Community Parks Initiative.

“This is not a light touch,” said Silver. “It’s scraping down to the dirt and rebuild an entire new park or playground for the 21st century.”

Residents’ responses to renovations were overwhelming

He recounted the reopening of Stockton Playground in Brooklyn, which had been an asphalt park built in the 1950s and was redesigned through the Community Parks Initiative:

“We put a new track, synthetic turf, landscaping. So, I asked one of my staff members, can you please ask this little boy — he was a Hispanic, about 8 years old — why he wouldn’t come into the park. And what he said was, the park was so nice he didn’t think it was for him. … He never saw anything like that in his neighborhood. [He thought] it was so nice, you had to pay. … His life and the [lives of the] children in that neighborhood will change because now they have something of value that they can call their own, where they can grow and make friends and connect with all of their family members.”

Silver also described the response from residents after work was completed on Grand Avenue Playground in the Bronx:

“The day we opened it, there were over 250 people waiting in line to get in the grand opening. And I’ll never forget this woman, in Spanish, came up to me and says, ‘Muchas gracias,’ saying, ‘You don’t know what this means. We can’t afford to go to places for vacation. This is where we take our children to play each and every day.”

So far, renovations have been completed on 47 of the 67 parks selected for the program, which will improve 70 acres of urban parkland when it’s finished. And 82% of the community parks have established “friends of” groups, which act as neighborhood-level conservancies. According to Silver, user ship has increased by nearly 50% at renovated parks.

Another 136 parks were slated for “smaller-scale” improvements such as repairing and repainting playground equipment, handball courts and benches.

Photos by NYC Parks

Houston has its own community parks initiative

Last October, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner launched the 50/50 Park Partners initiative — a public-private partnership to bring much-needed improvements and long-term support to 50 neighborhood parks with the help of 50 corporate sponsors. Similar to New York’s Community Parks Initiative, 50/50 Park Partners was set up to go beyond the city’s signature parks —Emancipation Park, Memorial Park, Discovery Green, MacGregor Park, Hermann Park and Bayou Greenways 2020 project — to renovate smaller, but no less important, parks in the city and increase equity, community engagement and sustainable impact. Twenty-two parks have been selected so far, based on facility needs and distribution. Working together, the Parks and Recreation Department, the Houston Parks Board, the Greater Houston Partnership and the city will select the program’s other 28 parks.

According to the “Resilient Houston” plan, the city is also working to address park equity by developing a park equity metric to guide and prioritize investment “in the development of new parks and the maintenance and programming of existing parks to alleviate disparities between different neighborhoods with variable levels of park space and income. The park equity metric will ensure that low-income areas have green space comparable in quality and quantity to middle- and high-income areas.”

It’s important to be near parks but quality matters

For planning experts like Silver, the egalitarian convictions shown long ago by Olmsted should apply to individual parks as well as the parks system as a whole. The gold standard for modern cities is putting a park or green space within a half-mile of every resident. Silver said 81.5% of New Yorkers live within a 10-minute walk of a park, with a goal of 85%. His claim is conservative compared to the Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore index, which puts 99% of New York’s population a 10-minute-or-less walk from a park because Silver’s standards for what constitutes a park is higher than theirs.

“It shouldn’t just be about proximity,” he said. “It should be about quality because I can walk to some of those ‘parks within a 10-minute walk’ and I would not let my child or grandchild play or step foot in that public space. And so, for us, equity became the keyword we wanted to pursue. And when I use the word equity — I don’t like these long definitions — it means fairness.”

Silver discussed the four characteristics of 21st century parks that set them apart from parks of the past.

Photo by Jeff Fantich

We are the placemakers, and we are the dreamers of dreams

Experience, memory and authenticity of place are important to people today. And this has changed the layout and amenities of parks.

“Previous generations were consumers of goods. New generations are consumers of experiences. We should not be just designers and planners, but experience builders,” Silver said.

It’s all about placemaking, according to Silver. Don’t just create a park or public space, make a place.

“When I look at a park, it’s not just designing green space,” he said. “It’s ‘how do we build an experience in this public space?’ And I know [Houston knows] how to do it because I see Buffalo Bayou Park, Hermann Park and Memorial Park. You know how to build those experiences at Levy Park. And that is what people are looking for.”

Furthermore, they aren’t just an amenity but a city infrastructure that must be integrated with the economy, environment and people in mind. And they are the first line of defense against climate change.

“Cities are being revitalized by focusing on their parks and public space because it makes cities livable,” Mitchell said. They also top the list of what apartment hunters in New York are looking for in a place to live. “It’s no longer schools. It’s access to parks and public space.

“I know people like their backyards but you can’t run five miles in your backyard. You can’t bike 10 miles in your backyard and you certainly can’t have a 20,000-person concert. So, our public spaces are revitalizing cities across the country.”