The Opportunity Zone program is probably the most important new federal program to address urban revitalization in decades. It’s a program that holds great potential to help Houston’s underserved neighborhoods – and also holds great risk in accelerating gentrification, especially inside the Loop.

The opportunity zone idea is basically an attempt to lure investors who are sitting on unrealized capital gains to invest in underserved, mostly urban neighborhoods. If you invest in these neighborhoods, you can defer capital or reduce gains, and if you wait long enough you don’t have to pay any capital gains at all. The idea is that, because investors are trying to avoid paying taxes on capital gains, there are a lot of investors sitting on the sidelines with capital to invest. Opportunity zones hold the potential to lure those investors into underserved areas. Already, many investment funds have been created to take advantage of opportunity zones.

To qualify, investors must meet certain criteria – still being worked out by the federal government – that include investing in businesses that do most of their business and generate most of their sales in opportunity zones. In Texas, the opportunity zones were selected by Gov. Greg Abbott in consultation with local officials. The program is seen as extremely favorable to real estate investments in particular.

But unlike most other federal revitalization programs, opportunity zones come with no government funding sources and no government qualification criteria. Other tax credit programs – such as, for example, Low Income Housing Tax Credits – come with an upper limit on the amount of tax credits, meaning that states must allocate those tax credits to certain investments.

Opportunity zones hold no such restrictions. There’s no limit on the amount of investment – or the amount of capital gains deferred and forgiven. And there’s almost no way for a city to track opportunity zone investment. No government agency other than the Internal Revenue Service need be informed that an investment is made.

"Some are areas clearly in distress. Others, not so much," according to a 2018 Brookings Institution analysis of designated opportunity zones across the country. Loopholes allowed some states to direct investment to areas that didn't seem to need it. And, as the analysis notes, thanks to regulations released in October 2018, up to 30 percent of opportunity zone funds can be invested outside of the qualified zones.

There’s no question that – whatever hope they hold to improve underserved neighborhoods – opportunity zones also hold the risk of accelerating gentrification in Houston. Gentrification is typically defined as a situation where longtime residents of an underserved neighborhood are squeezed out by rising property values that result from new investment.

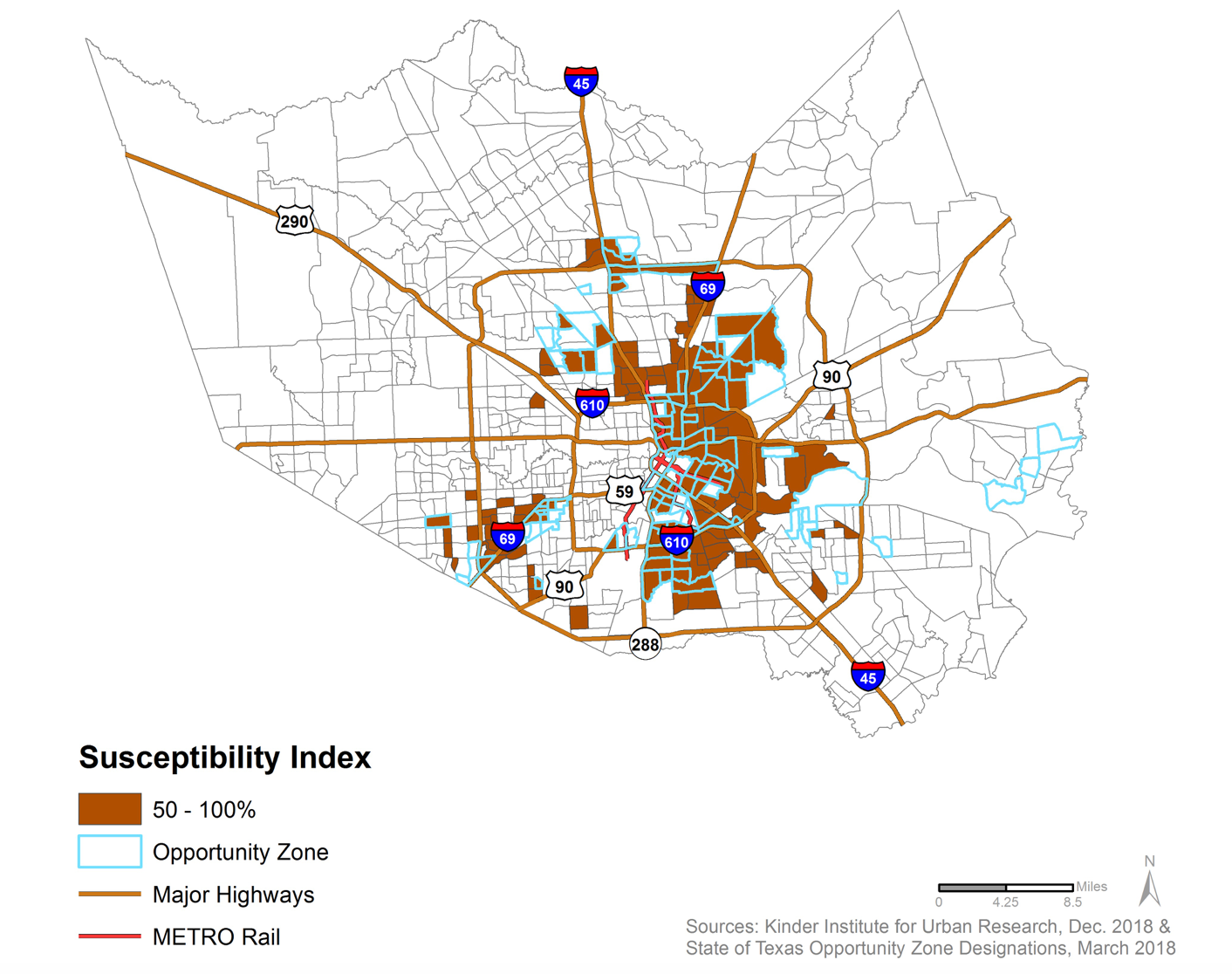

Recently, the Kinder Institute examined gentrification locally and concluded that virtually all of the neighborhoods on the east side of the Loop are likely to gentrify over the next few years.

If you overlay the opportunity zone map on top of those results, the risk of “gentrification on steroids” becomes obvious: Two-thirds of the neighborhoods susceptible to gentrification in the near future are located in opportunity zones. It’s entirely possible that opportunity zone investments – which should be a good thing – will accelerate the gentrification process that’s already underway, especially on the east side of the Loop.

Credit: Wendie N. Choudary.

So how can Houston make sure that opportunity zones help current residents of underserved neighborhoods rather than pushing them out?

Many cities are trying to steer opportunity zone investors toward specific types of investments, in a couple of different ways.

First, a lot of cities are marketing their opportunity zones but putting together what they’re calling a “prospectus” – essentially, a marketing package describing their opportunity zones and the types of investments that are available there. Oklahoma City even went so far as to group their opportunity zone neighborhoods into eight districts and give those districts names. In Houston, Councilmember Amanda Edwards is leading the charge to create a prospectus.

Second, cities are trying to sweeten the pot by encouraging opportunity zone investors to make investments that qualify for other city economic incentives – for example, tax-increment financing, which provide financing for infrastructure, and 380 agreements, which provide property tax abatements for certain types of investments. Unlike opportunity zones, such incentives are within the control of the city (or subsidiary entities like Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones, or TIRZs). So only the city can increase the value of an opportunity zone investment by combining it with these other incentives. Nonprofit organizations such as community development corporations can combine opportunity zone investments with other tax credits such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit.

Such incentives are especially important in a city like Houston which does not have conventional zoning. In most municipalities, the city could block or incentivize certain types of real estate investments through zoning – by prohibiting industrial development in an opportunity zone, for example, or increasing the density allowed for residential projects around a light-rail stop. Houston can’t do that, so using the economic incentives that are available will become more important.

The opportunity zone is a funny animal compared to the typical federal program – it’s driven mostly by private investors with few rules imposed by local government, and indeed cities won’t always know where these investments have been made. The risk of accelerating gentrification is real. If Houston and other cities use the other tools at their disposal to nudge opportunity zone investors into certain types of investments – say, affordable housing – the likelihood that these investments will benefit the people who currently live in underserved neighborhoods will increase.