The neighborhoods we live in have a lot to do with the lives we lead. There's a robust body of scholarship around the phenomenon known as neighborhood effects that argues exactly that. In an attempt to understand things like durable segregation and inequality, researchers have shown that individual-level outcomes can be linked to structural-level characteristics of the communities we live in. Now, a new interactive tool from the Census Bureau and researchers at Harvard University and Brown University seeks to better capture the impact of neighborhoods using longitudinal data for children born between 1978-1983 across a variety of demographic groups.

The results are, if not surprising, still stark and show uneven maps of opportunity, intertwined with race. "Using de-identified data covering 20 million children and their parents," the researchers wrote, "we show how race currently shapes opportunity in the U.S. and how we can reduce racial disparities going forward."

National patterns

While the researchers found evidence that Hispanic families have experienced some upward mobility, black and American Indian children were much less likely to experience that same upward mobility. "For example," the researchers found, "black children born to parents in the bottom household income quintile have a 2.5% chance of rising to the top quintile of household income, compared with 10.6% for whites." In fact, black and American Indian children were more likely than other groups to experience downward mobility. "Black children born to parents in the top income quintile are almost as likely to fall to the bottom quintile as they are to remain in the top quintile," the researchers concluded. "By contrast, white children born in the top quintile are nearly five times as likely to stay there as they are to fall to the bottom."

And though many argue things like family composition, educational attainment and differences in wealth explain the black-white income gap, the researchers say that's not the case. Importantly, these gaps, which the researchers argued were tied to male outcomes and not female outcomes, are present almost everywhere. "Black-white disparities exist in virtually all regions and neighborhoods," the researchers write. "Some of the best metro areas for economic mobility for low-income black boys are comparable to the worst metro areas for low-income white boys."

Significantly, however, the researchers were able to use the data to determine that, for example, black boys who move to more advantaged neighborhoods when they're young, experience better outcomes, underscoring one of the lessons of the Moving to Opportunity experiment that sought to relocate housing voucher holders to better neighborhoods. One of the findings to come out of that effort was that young children who moved saw benefits while teenagers did not. By documenting again that young children can reap the benefits of the advantages that cluster in certain neighborhoods, the researchers were able to underscore that racial disparities in income were not a given. "The challenge is that very few black children currently grow up in environments that foster upward mobility," the researchers concluded.

Because neighborhoods serve as clusters of either disadvantage or advantage, interventions aimed at reducing poverty must work with that in mind. Policies should seek to reduce residential segregation within neighborhoods, the researchers argued.

Houston-area patterns

At the national level, newly created Opportunity Zones offer one of the latest place-based approaches meant to funnel resources and investment to targeted areas.

At the local level, the segregated reality of opportunity has spurred a number of responses. On the one hand, fair housing advocates have pointed to the inequality and argued for more subsidized housing within advantaged neighborhoods. But Mayor Sylvester Turner - whose decision not to move forward on a proposed low-income housing tax credit project in a wealthy Houston neighborhood garnered federal scrutiny in a recently settled but still controversial investigation by the federal housing and urban development department - has repeatedly argued that residents shouldn't have to move to an area with opportunity to access it.

"I will not tell kids who live in low-income communities the only way to achieve the American dream is that I must build housing in neighborhoods away from where they are," his official account tweeted Saturday. "Do not give us a small boat that will save some, help us fix the ship that will save many."

To that end, the mayor launched his Complete Communities initiative in five pilot neighborhoods that engaged in a months-long planning process to articulate short- and long-term goals. Without dedicated funding, however, the success of the action plans has yet to be fully realized.

The five neighborhoods, selected in part because of a history of underinvestment, reflect broader patterns of opportunity and inequality.

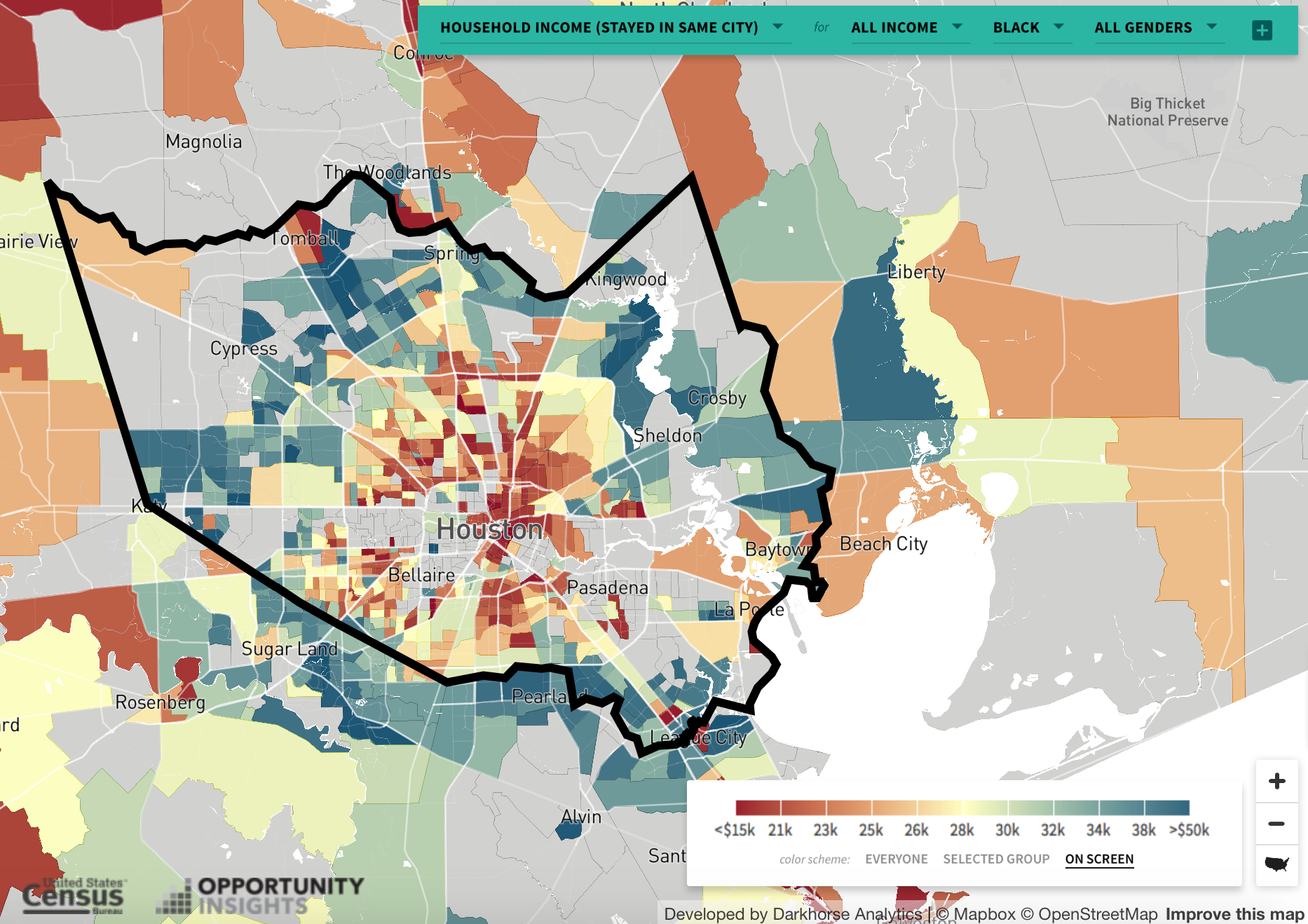

In the northern census tract of Third Ward, for example, black children who grew up there had an average household income of $20,000 in 2014-2015, regardless of parent income growing up.

In Acres Homes, in one of the central census tracts bounded by Wheatley Street to the east, Cebra Street to the west, West Little York Road to the north and Creekmont Drive to the south, black children from households where their parents income was in the 75th percentile, had an average household income in the 47th percentile for the Houston area—here referring to more or less the area inside the Grand Parkway—or roughly $37,000. Percentiles are adjusted by scale and vary depending on the geography included. Though that tract did not have enough data to compare outcomes for white children, the tract just to the east, diagonally intersected by West Montgomery Road does. There, black children whose parents' incomes were in the 75th percentile ended up in the 59th percentile of household income while white children whose parents were in the same 75th percentile ended up in the 99th percentile, earning around $85,000.

In one of Gulfton's census tracts, east of Renwick Drive between Gulfton Street and Bellaire Boulevard, children from low-percentile households, those where the parents' income was in the 25th percentile, later had average household incomes of $33,000. But broken out by race, the numbers vary. So Hispanic children from low-percentile households there could actually expect to do a little better, earning an average $36,000 in household income. Black children from low-percentile households fared worse, going on to earn around $28,000 on average in household income while low-percentile Asian children saw the most upward mobility, eventually earning an average $71,000 in household income.

All of this points to the fact that opportunity is not evenly dispersed across the city but it also suggests that even within certain neighborhoods opportunities are not equally accessible.

Map of average household income by census tract for black children who stayed in the city. Source: Opportunity Atlas.

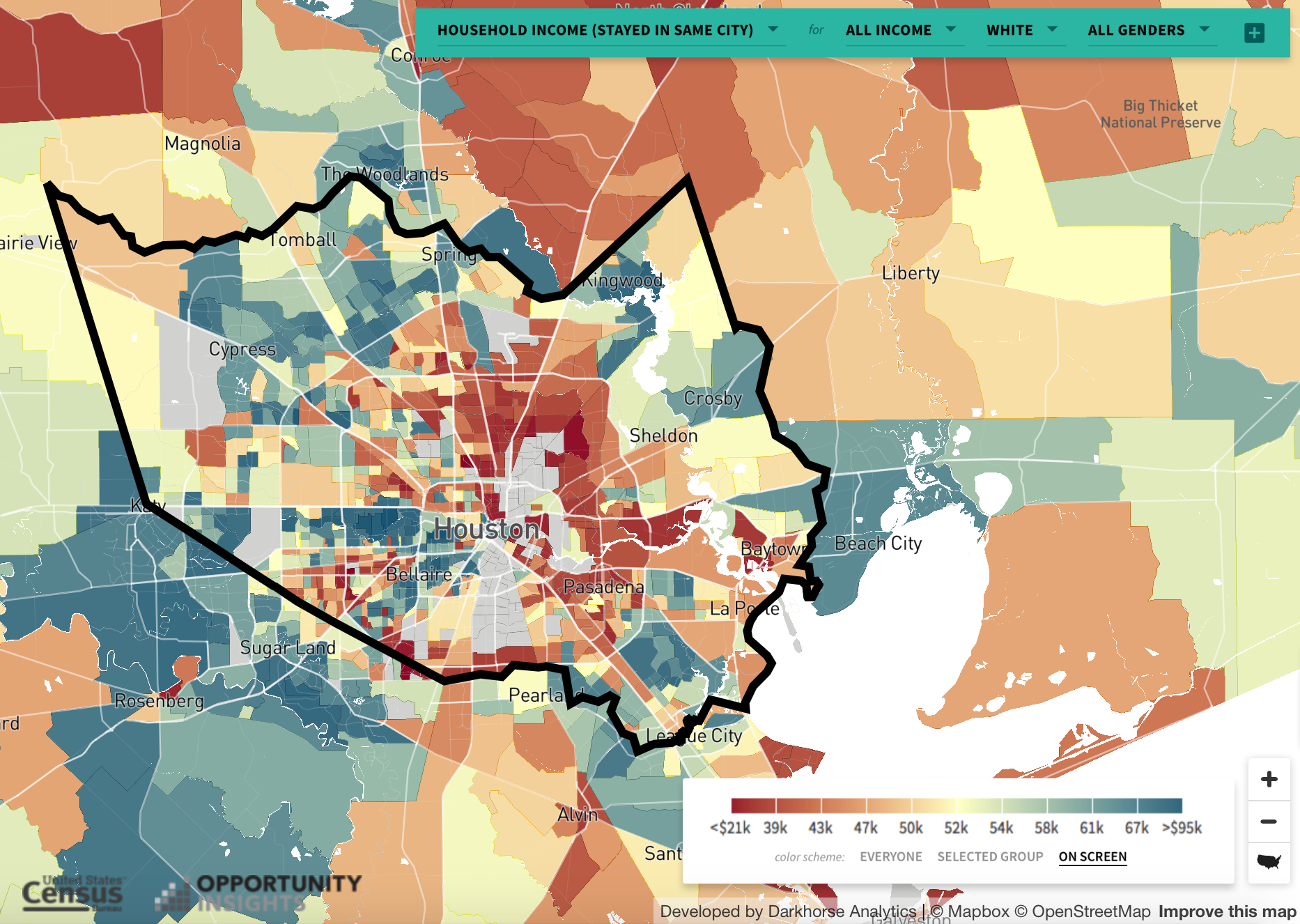

Average household income for white children who stayed in city. Source: Opportunity Atlas.

The interactive map also points to longer-term demographic trends in the region. So while 67 percent of white children in Harris County stayed in the same city as of 2015, 70 percent of both Asian and American Indian children stayed and 85 percent and 87 percent of black and Hispanic children stayed. The outcomes for each of these groups varied both between groups and across geographies.

White children who stayed had an average household income of $56,000 and Asian children who stayed had an average household income of $60,000. Hispanic children, meanwhile, saw an average household income of $41,000 while black children who stayed saw just $27,000 in average household income.

But each group saw variation depending on where in the county they grew up. So black children who grew up inside Beltway 8, with a few exceptions, had much lower average household incomes than those that grew up outside, showing a stark contrast in opportunity. By contrast, white children who stayed in the city had many more opportunities for better outcomes within the city's core, primarily in the area pointing toward downtown from the west. The gray areas also show the spaces where segregation was, and largely continues to be, so severe that data collection wasn't possible at that geographic level for those groups.

Furthermore, 25 percent of, or one in four, black children from low-income households in Harris County lived in the exact same census tract as where they grew up in 2015, compared to just 17 percent of low-income white children. Low-income Asian and Hispanic children were also more likely than their white peers to live in the same census tract as adults, at 26 and 30 percent.

The overall picture is one of mobility, both geographic and socioeconomic, for some, and not others, largely structured along race. As Greg Russ, head of the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority, told the New York Times about the data and how he plans to use it: “Is opportunity a block away? These are the kind of questions we can ask.”