Gentrification pressures exist in nearly every metropolitan area. Houston is no exception, as our new report shows.

In order to understand neighborhood change in Houston, we identified which neighborhoods experienced gentrification between different time periods. Gentrification, the process of higher-income households moving into traditionally lower-income neighborhoods, has transformative effects on neighborhoods. Current residents are overburdened and financially stretched, while potential lower- to moderate-income families discover preferable neighborhoods are now inaccessible. Rising costs in gentrifying neighborhoods not only reduce affordable housing options, but also threaten social networks and longstanding amenities.

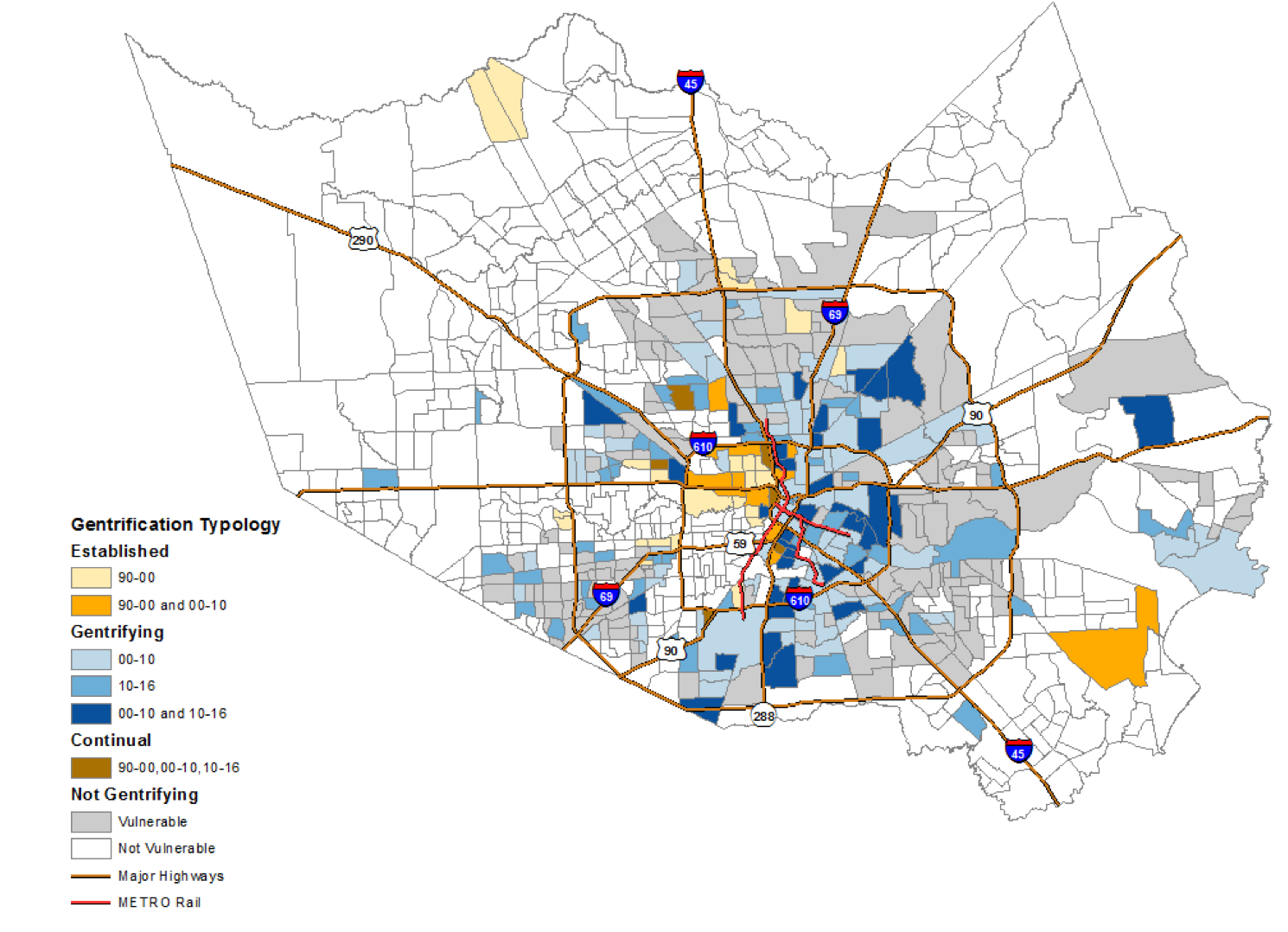

Harris County gentrification. Source: Kinder Institute.

As Houston continues to grow, it is important to know what neighborhoods will be at risk for unwanted neighborhood change. Therefore, our report reviewed the mechanisms of gentrification in Houston, predicting neighborhoods’ susceptibility to future gentrification. Interestingly, we found gentrification has accelerated since 2000 and a greater number of neighborhoods gentrified outside the 610 loop. The susceptibility index revealed that nearly all neighborhoods on the east side of Houston inside the 610 loop are likely to gentrify in the near future. These patterns are displayed in this web-based data tool.

Our broad analysis of gentrification and susceptibility in Houston is meant to inform strategies to support equitable neighborhood change. Currently gentrifying and neighborhoods likely to gentrify may benefit the most from mitigating strategies.

Gentrification and susceptibility to gentrification is a far reaching phenomenon across neighborhoods in Harris County, both inside and outside the city core. Gentrification is not only present in the Houston area, but also across nearly every metropolitan area. Due to population growth since 2000, gentrification pressures are more recently emerging in the Sun Belt region when compared to other urban areas. These cities often share characteristics, such as growing populations, limited regulation and fewer expectations of government, which can make strategies for taking control of gentrification and unwanted neighborhood change different from those in places like Chicago, New York or Seattle. In fact, as Mary Newsome, a prominent scholar in Sun Belt region studies, has shown: there are opportunities for these similarly positioned Sun Belt cities to learn from each other.

Houston

Unlike other major cities, without citywide zoning, Houston communities must have some know-how to utilize various local land-use tools, such as minimum lot size protections, minimum building lines and Chapter 42, the city’s land development ordinance, to preserve community and prevent real estate developers from subdividing the plats and replacing old homes with townhomes. In addition to the ordinances mentioned above, private agreements such as deed restrictions and homeowner associations can also provide some kind of protection. But these tools are not without their own consequences and their application is often complicated.

In some Houston communities, as shown in the report’s case study selections, including the Fifth Ward and OST/South Union, place-based strategies include Community Development Corporations partnering with ongoing citywide efforts to leverage resources for comprehensive plans in developing projects while preserving cultural histories. Other community-based organizations, like Agape Development Ministries located in OST/South Union, provide support to existing low- to moderate- income residents through access to homeownership, purchasing vacant land for affordable housing construction and giving renters not only a chance to be homeowners, but a voice in the development of their homes and community structures. Financial literacy education is also provided. However, with limited resources and capacity, community-based organizations cannot fully implement the tools and strategies to help the community grow while protecting it from undesirable private development.

In terms of state and local policies, the city's land trust efforts, public housing, housing choice voucher programs and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit can potentially offer tools to preserve housing affordability in gentrifying neighborhoods. But each of these efforts face significant challenges, not the least of which is documented discrimination.

In Houston, land-use strategies, place-based strategies and state and local policies are considered, yet their success is mixed and inconclusive. Further policy analysis is needed to fully assess the effectiveness of these tools and to identify the best way to apply those strategies for various types of gentrifying neighborhoods.

Other Sun Belt cities have used similar approaches, but several unique approaches could be considered in the Houston area as well.

Los Angeles

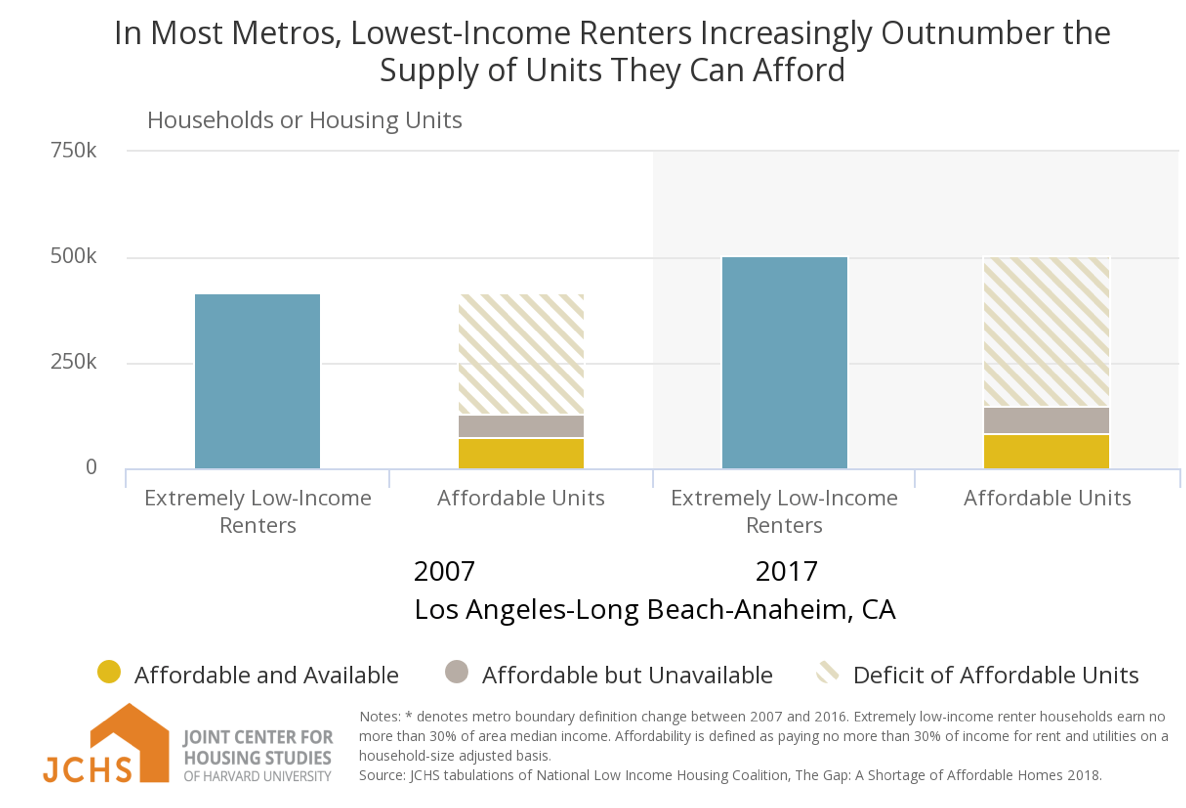

The story of the lack of housing affordability in Los Angeles is a similar one to Houston: High disparity between low-income renter households and available affordable rental units. Due to the high cost of homeownership, there are more renters than homeowners, many of whom are extremely low- to low-income. Low-income renters have less access to rapidly changing neighborhoods and are more at risk of becoming financially overburdened or displaced.

Source: Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University.

In places like Koreatown, residents have moved out due to rent increases and gentrification pressures. Nearby neighborhoods like Filipinotown, Silver Lake, Echo Park and Boyle Heights are undergoing development and redevelopment. Longtime residents in Filipinotown worry an influx in market-rate multifamily buildings is attracting a new set of people and displacing existing residents. In order to improve the area, the Los Angeles Planning Department instituted the North Westlake Design District, a community master plan. A proposed master plan included requirements for pedestrian- and transit- friendly designs and placed regulations on the types of new construction, business signs, parking allotments for new developments, setbacks and other commercial specifications. But groups like the Los Angeles Tenants Union, activists, and neighborhood groups spoke out against the design district plan, saying it did not include affordable or low-income housing options, rather more market-rate housing. As many existing residents are longtime small business owners, the plan would make it harder for business owners to succeed. Ultimately, propelling gentrification rather than curbing it. Activists and local groups successfully pushed for a new plan to provide a way for them to work with developers and businesses to promote Filipinotown’s cultural history. That plan is now being drafted.

Activism is only one method residents across Los Angeles have utilized.

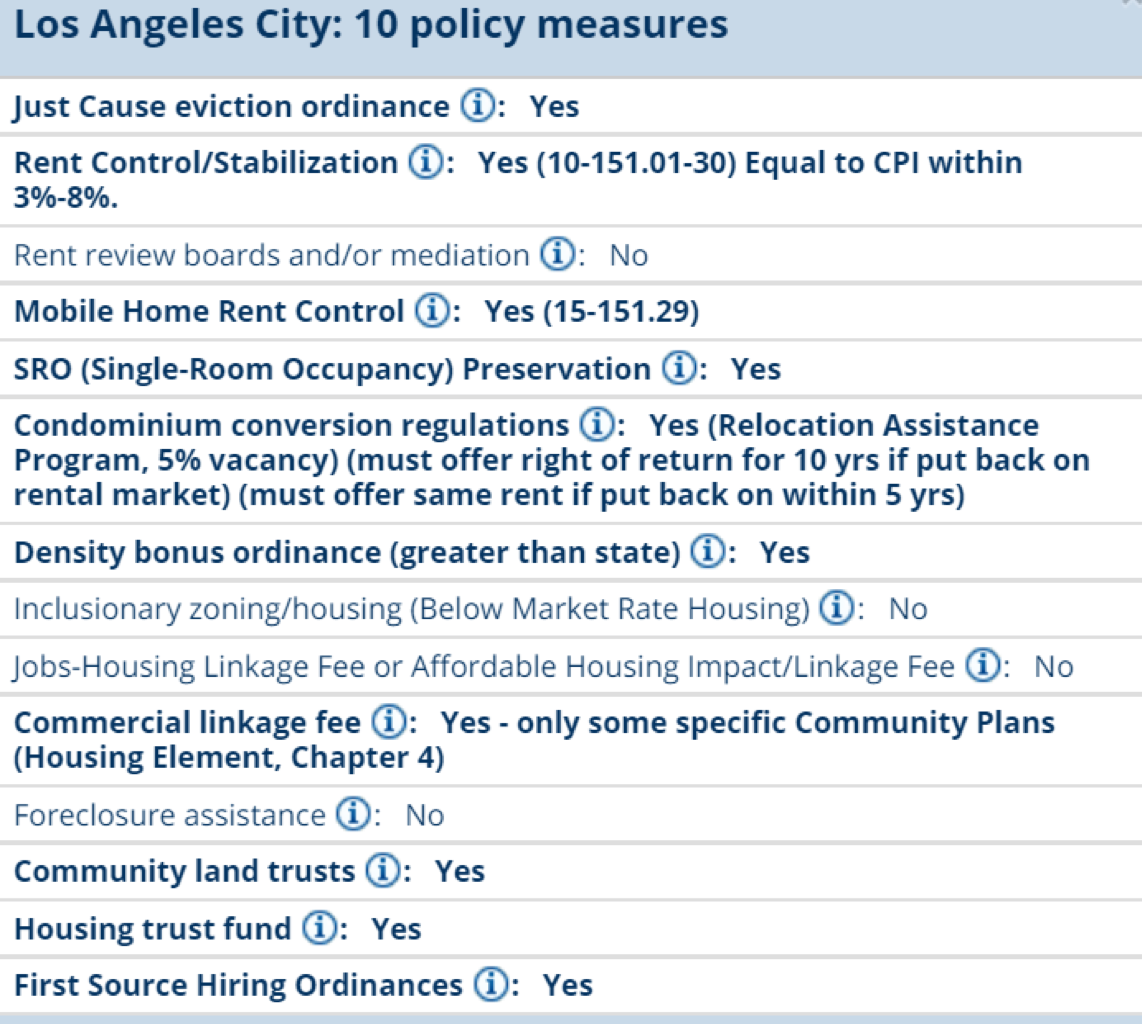

Los Angeles, though similar to Houston’s demographic makeup and auto-oriented characteristics, has far more land and housing regulations than Houston. According to UC Berkeley's Urban Displacement Project, despite a wide range of anti-displacement policies and strategies in Los Angeles County, their coverage is fragmented and implementation is not equitably distributed across jurisdictions.

A similar inventory of anti-displacement policies and strategies for the Houston area would be beneficial. Knowing exactly where particular policies are and are not in place, such as minimum lot size restrictions, would better help homeowners plan and strategize for the use of such land-use policies.

Los Angeles has tabled other responses to rising gentrification pressures. For one, the city allowed landlords to rent out unpermitted apartments if they also provided affordable housing options. In a given year, landlords are forced to remove 400 to 500 rental units not approved for occupancy, such as converted recreational rooms and micro apartments. When housing units are not in compliance after housing inspections, about 80 percent of tenants in those units are evicted. As long as these unpermitted units are brought into compliance with city safety codes, landlords can make the income, but they must agree to rent an equal number of units in the building at affordable prices for the next 55 years.

Another response forces developers to pay for affordable housing. Housing linkage fees are development impact fees assessed on new construction of commercial and residential buildings. The funds from fees from construction of new units goes under deed restrictions to tenants with qualifying incomes. Some of the funds are meant for rehabbing and maintaining existing affordable housing units. For example, new affordable housing would be subsidized by public funding. Developers pay $5 per square foot of commercial space (hotels, restaurants, shops) and $12 per square foot for residential space (apartments, condos). This would generate $75 million to $92 million each year toward preserving neighborhoods.

Austin

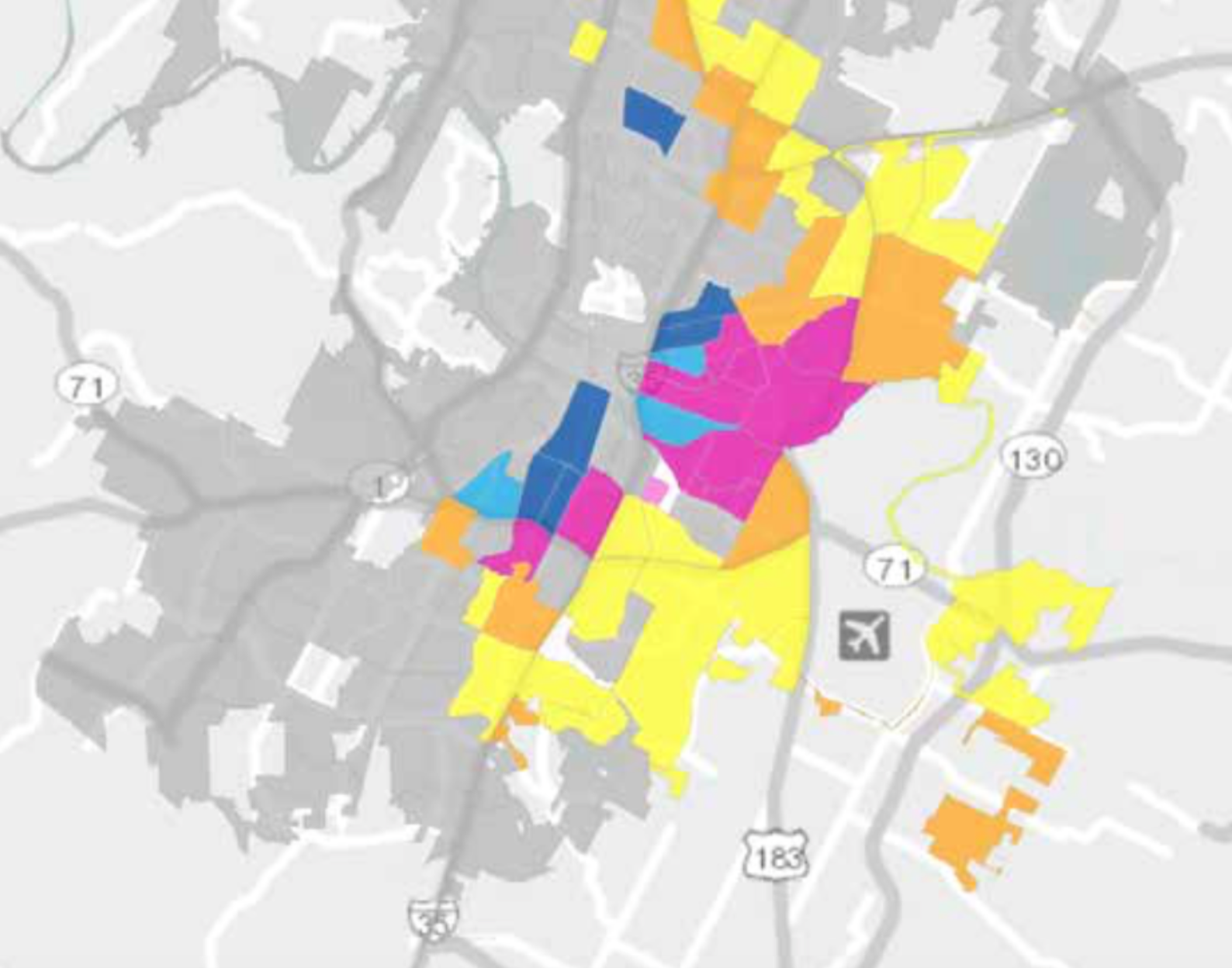

The City of Austin has taken up gentrification concerns with mixed success. From the top-down, the city decided to completely rewrite its land development code, impacting affordability, transportation and the environment. The ill-fated effort was known as CodeNEXT before the mayor decided to table the years-long process, promising to take up the issue again. Alongside CodeNEXT, a bottom-up People’s Plan was also crafted, urging city officials implement anti-displacement strategies, particularly in response to gentrification pressures in east Austin. The City Council approved the plan’s resolutions for further analysis and action.

The plan consists of six resolutions that utilize public funds and city land to improve infrastructure, provide affordable housing in high-risk areas and allow for measures for displaced residents to return:

1. Interim land restrictions to limit the degradation of natural and cultural environment

2. Low-Income Housing Trust Fund that would target public investments to low-income housing (modeled on Denver’s plan)

3. Create 2,000 low-income housing units using city-owned public land

4. Implement East Austin Neighborhood Conservation Program with Conservation and Historic Preservation Districts to restrict land use

5. Enact Right to Return and Right to Stay programs to help at-risk residents stay in and return to their neighborhoods (modeled on Portland’s Right to Return plan)

6. Enact local environmental quality review program to ensure environmental justice

With the CodeNEXT initiative stalled, Austin recently passed Prop A housing bond of $250 million for affordable housing, with $100 million for land purchases by Austin Housing Finance Corporation for future development and other developers of affordable housing. Meanwhile, $94 million will support affordable rental housing, including permanent supportive housing. The remaining $56 million will help maintain existing affordable housing utilizing the “Go Repair!” program, as well for the acquisition and development of low- and moderate-income homeowner housing.

Houston, with the right backing, could expand funds for its New Home Development Program which provides new, affordable single-family homes for qualified low- and moderate-income homebuyers. Furthermore, Return and Right to Stay programs like in Austin would help many residents in Houston, who were displaced not only by uninhabitable housing but also by rising housing costs. Planning for environmental justice and equitable development are particularly necessary for development along bayous.

Austin neighborhood typologies, 2016. Dark Blue: Continued Loss. Blue: Late. Dark Pink: Dynamic. Light Pink: Dynamic (Rent Data). Orange: Early: Type 1. Yellow: Susceptible. White: Susceptible (Rent Data). Gray: Study Area. Source: UT Austin.

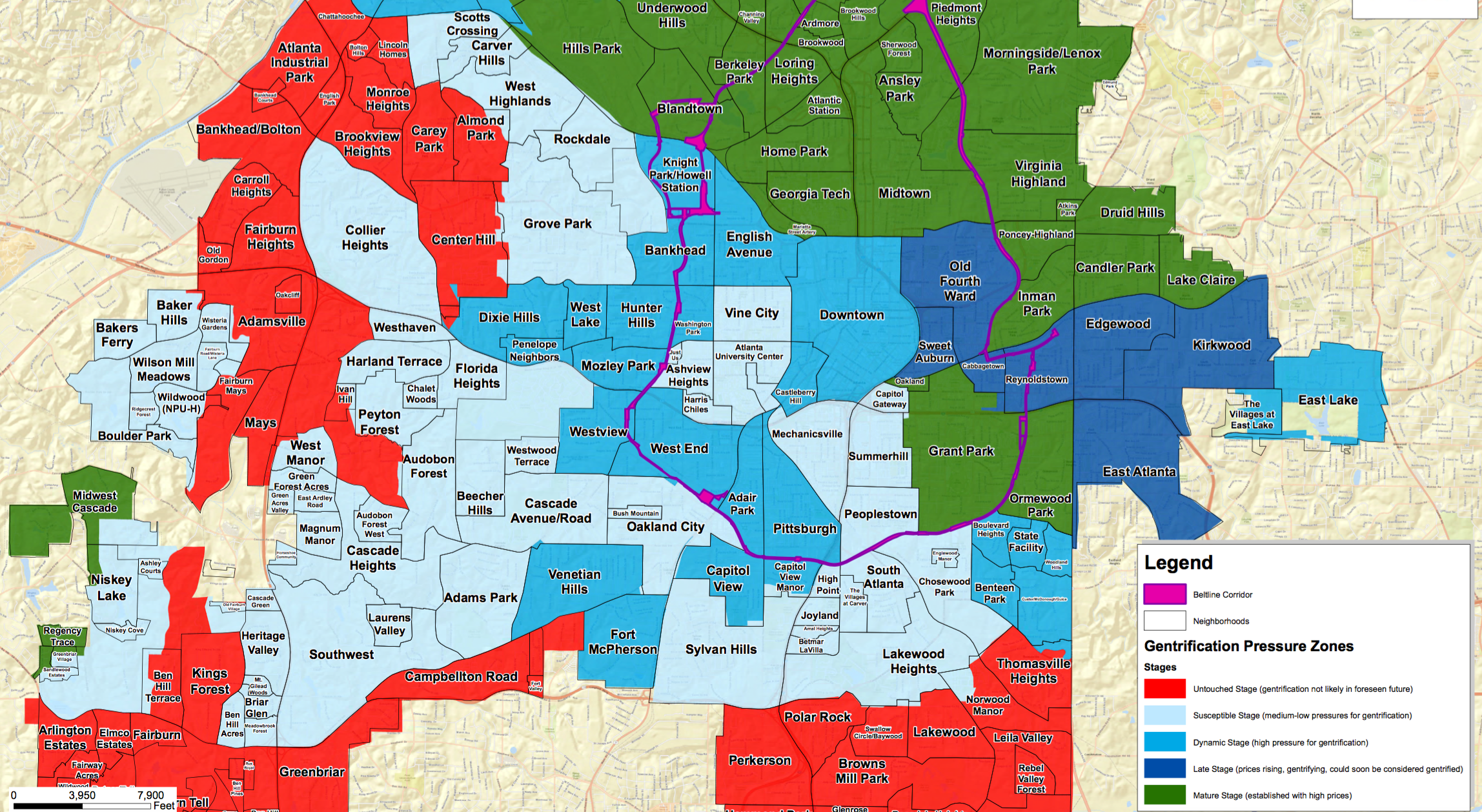

Atlanta

Similar to other Sun Belt cities, rising development has had an impact on housing affordability in Atlanta, particularly BeltLine development. A recent report by the City of Atlanta’s Department of City Planning identified where gentrification pressures are the highest, including along the BeltLine corridor.

Source: City of Atlanta.

In March 2018, the Atlanta mayor announced three new affordable housing programs (Atlanta Heritage, Westside Heritage and Choice Neighborhoods Heritage) to prevent low-income households from being displaced, totaling an investment of $9 million. The three programs, implemented by Invest Atlanta with the Atlanta Housing Authority and Choice Atlanta, are considered Heritage Owner-Occupied Rehab programs that provide forgivable loans to residents to make repairs to their homes.

Heritage OOR programs require certain criteria, including minimum and maximum incomes, and are prioritized by neighborhoods, disability or veteran status and whether the resident has been in the home for 15 years or more.

Atlanta leaders suggest OOR programs could end up helping nearly 20 percent of homeowners, predominantly in Westside neighborhoods such as Vine City, English Avenue, Castleberry Hill and in Choice neighborhoods like Ashview Heights and Atlanta University Center Communities. So far, this program has helped homeowners repair decaying roofs, pipes, electrical installations and other housing quality aspects. Residents can apply for up to $60,000 in forgivable loans for these repairs, meaning the loans would be forgiven in exchange for making the repairs.

Houston could expand its existing home repair loan assistance program and also consider working on public-private partnerships similar to the City of Atlanta’s partnership with Invest Atlanta to cut costs to serve more homes. Work like this would further relieve financial pressures facing people on the brink of being displaced.

The City of Atlanta also utilizes land-use policies, such as urban enterprise zones, based on the Atlanta Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ) Act. An urban enterprise zone is a designated district that is located within an economically‐depressed area of the city where property owners receive tax abatements over a 10‐year period, if certain conditions are met. Further, homestead exemptions were recently updated to reflect increases in home values and its assessed values’ subsequent tax burdens to homeowners. Therefore, over time, a gradual $15,000 to $30,000 increase provided relief to homeowners. A review of Houston’s homestead exemptions may be beneficial to local residents.

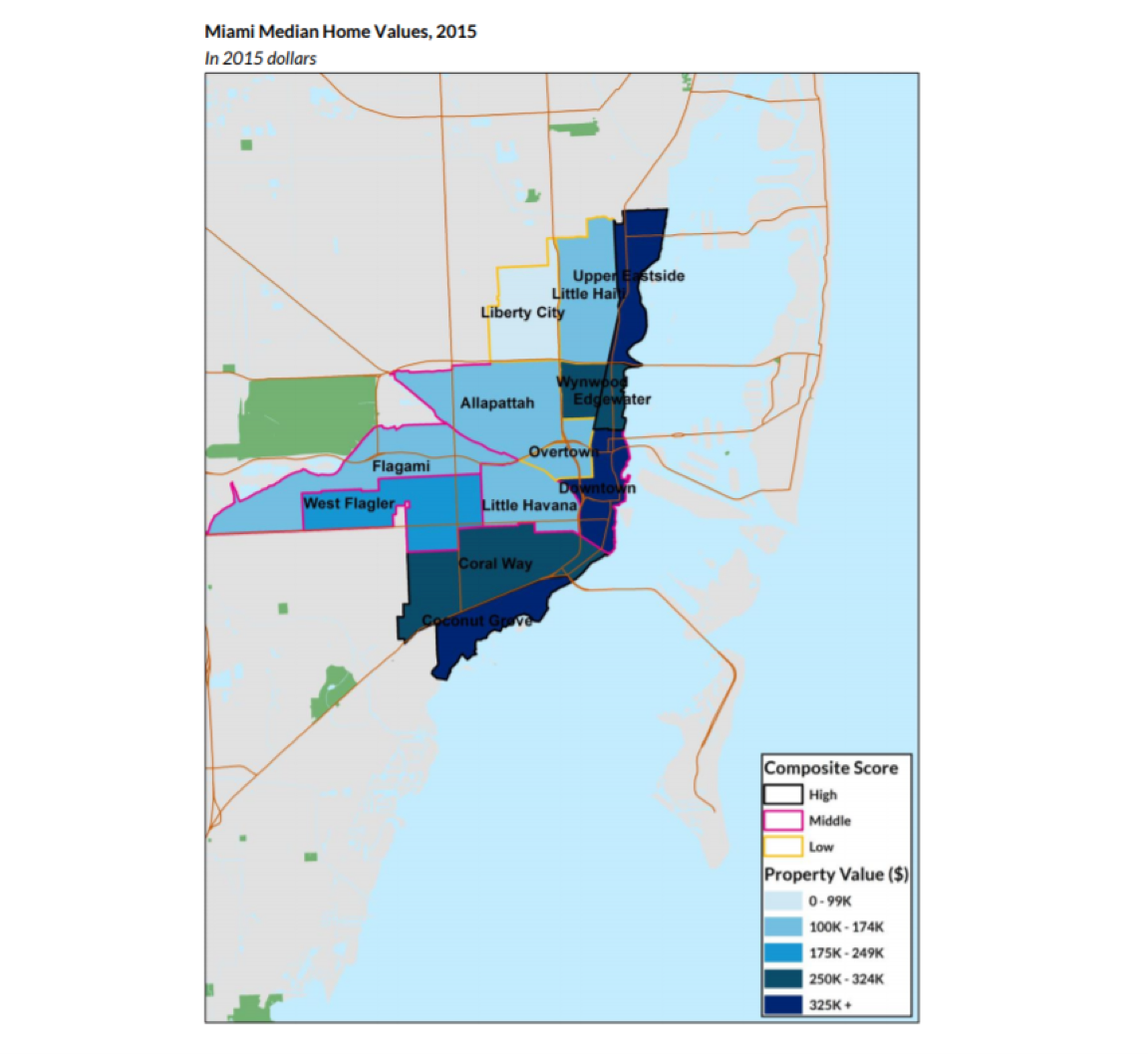

Miami

Similar to Houston, Miami’s immigration context is reshaping its social and political landscape. In-depth research from the Urban Institute detailed the often confusing nature of gentrification in Miami. Real estate speculation, high-end businesses and luxury condos are edging out family-owned business and making rent and monthly housing costs unreachable. Neighborhoods such as Wynwood and Edgewater have seen unwanted neighborhood change that is destabilizing surrounding communities like Little Haiti and Allapattah. Little Haiti is coveted for its proximity to downtown, the airport and its less flood-prone, higher altitudes when compared to Miami Beach, which will possibly be under water in the next 30 years. Allapattah is a predominantly Dominican community with multigenerational families who live and work as entrepreneurs in the neighborhood.

Source: Urban Institute.

The Urban Institute recommended local organizations convene and start community-led initiatives for economic and neighborhood development by creating a consortium to help renters, homeowners and small business owners enhance low-income household incomes and remain in their homes. The consortium would work like a bank, financing property maintenance and helping to preserve affordable housing options for renters, as well as educating renters on homeownership. It could also help preserve and promote entrepreneurial skills and community culture.

As in Houston, developers in Miami have leverage over affordable housing proposals and policies at the county and city levels. Organizations in Miami, such as Miami Homes For All (MHFA), Miami’s People Acting for Community Together (PACT) and Struggle for Miami’s Affordable and Sustainable Housing (SMASH) have created campaigns across distressed communities, giving residents a voice; however the Urban Institute suggests an alliance with developers is needed to leverage affordable housing development.

Houston, too, can organize around collaboration among community organizations, city planning and policies, with developers. Considering Houston’s overall decrease in median household income, improving educational attainment and building-up entrepreneurial businesses in order to increase residents’ earning potential are also housing affordability-related strategies that invest in people as well as places.

Looking at gentrification and anti-displacement polices across select Sun Belt cities adds another element to the Kinder Institute’s gentrification report, providing potential directions that are not yet readily available to Houston residents or could be expanded. Suggested strategies could be utilized in currently gentrifying neighborhoods as well as those neighborhoods susceptible to gentrification.