With many cities contending with affordable housing shortages, struggling schools and income inequality, a new survey of mayors from across the country shows that most mayors believe various groups in their cities face discrimination and unequal access to services but that they believe it's not as severe as in the rest of the country and that the quality of services, with the exception of education, is the same for all constituents.

The report from the National League of Cities and The Boston University Initiative on Cities drew from data collected in 2017 as part of the Menino Survey of Mayors with responses from 115 mayors in 39 states. The results suggest that mayors are both aware of inequality in their own cities but that their own "aspirations, intentions or the current allocations of dollars in their city" may affect how they view it and its causes.

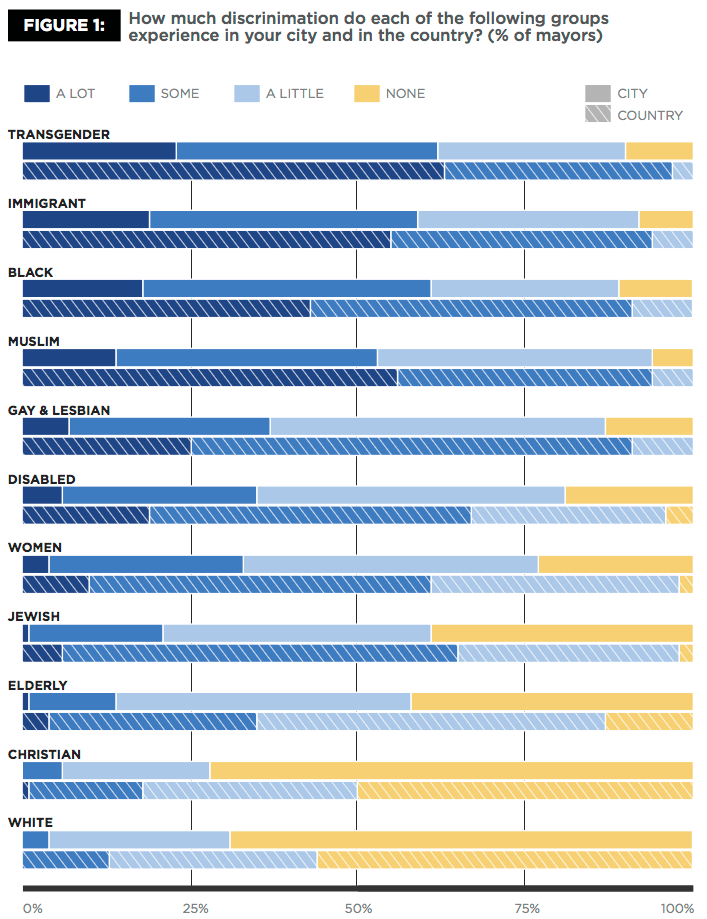

Mayors were, for example, much more likely to say that various groups, including transgender individuals, immigrant populations, black people and Muslims, among others, experienced less discrimination in their city than in the rest of the country. So while just under 25 percent of mayors said transgender individuals faced "a lot" of discrimination in their city, well over half of mayors said the same for the rest of the country. Part of this gap may be that mayors are aware and apt to cite initiatives and policies at the local level, like a transgender liaison in the police department, and might be less familiar with efforts elsewhere.

Source: National League of Cities and The Boston University Initiative on Cities.

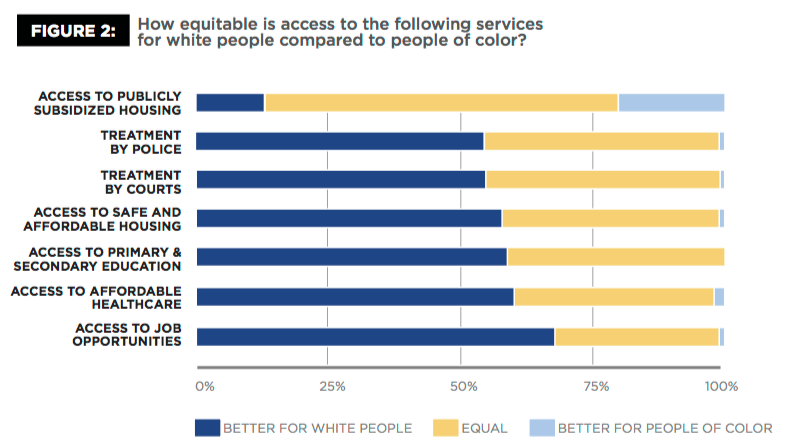

Perhaps more telling though were the assessments of access to and quality of services for different groups. Mayors generally felt that access to things like affordable housing, job opportunities and healthcare, as well as, treatment by the police and courts was better for white people than for people of color. The only exception was for access to subsidized housing.

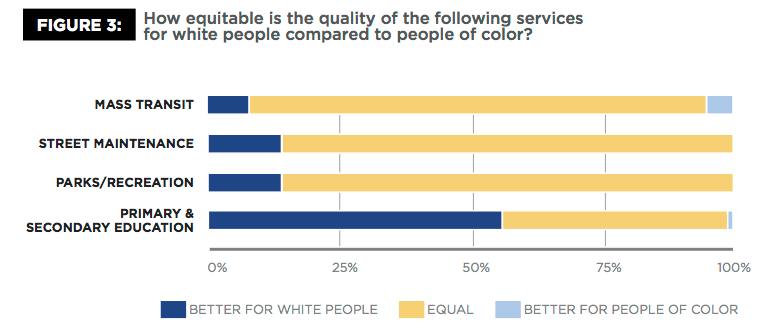

But when it came to quality of services like mass transit, street maintenance and parks and recreation, respondents overwhelmingly felt that things were equal for white people and people of color. The only exception here was primary and secondary education, which one mayor explained saying, "We don’t control the schools, so our efforts are focused on ensuring all neighborhoods are accessible to all residents which increases the likelihood that people can access the best performing schools. We are working to ensure access to affordable housing throughout the city.”

Source: National League of Cities and The Boston University Initiative on Cities.

Source: National League of Cities and The Boston University Initiative on Cities.

The research suggests, however, that those things probably aren't all that equal. In Houston, for example, of the 9.3 percent of people who have access to high-frequency transit around the clock transit, 39.7 percent of them are white versus 15.9 percent black and 32.5 percent Hispanic, according to the Center for Neighborhood Technology. Metro uses its own definition of high-frequency that changes these results but as a metric of access to very consistently frequent transit, the first measure is still telling. When it came to parks, surveys found that park users in majority non-white neighborhoods wanted better park amenities like clean and functioning restrooms, enhanced maintenance and a safer environment—concerns that differed from surveys of mostly white respondents. That's likely because, even if those neighborhoods had access to parks, those parks were not given the same attention as parks in whiter spaces. Houston is not alone in this.

Not all mayors thought all was equal. "Some mayors interviewed did note the importance of acknowledging and remedying inequity in the physical environment," the report notes. "As one mid-sized city mayor expressed, a mayor needs to be 'super honest on this stuff. Richer areas have nicer roads and parks.'"

And the report suggests this an area where mayors can both be more critical and perhaps find more responsive systems for acquiring feedback on some of these services. "The lack of awareness of potential inequities in streets, parks and transit suggests an opportunity for mayors to make use of new, more rigorous tools to evaluate the quality and prioritize capital investments," the report argues. Complaint-based systems, for example, could misrepresent on the ground quality differences. As one survey respondent put it: "The nicer parks are in neighborhoods with people exercising civic roles and calling the city to complain when parks get dirty. In minority communities, there are fewer complaints and calls.” Because complaint-based systems rely, in part, on trust from the neighborhood that those complaints will be addressed and time and resources of those constituents with the city and those services, they can skew attention toward already resourced areas.

The study lays out a number of strategies for cities interested in address inequality more deeply, including open conversations about a history of injustice familiar to many cities. Another strategy involves disaggregating data about service access and quality by race and other factors for more meaningful assessments.

"Mayors play a critical role in the work of combating discrimination," the report argues. "In addition to setting budget and policy priorities for local governments, a mayor’s leadership, actions and words influence the attitudes of the community."