In 2015, Texas became the only state in the country to pass a law protecting a landlord's ability to refuse to accept housing vouchers.

A new federal lawsuit filed last week alleges that law is unconstitutional and violates the Fair Housing Act.

The 2015 statute was passed in response to Austin's attempts to ban landlords from discriminating against housing choice voucher holders, who were concentrated in limited parts of the city. The plaintiffs, the Dallas-based Inclusive Communities Project, alleged the practice of refusing vouchers perpetuates racial segregation.

In Dallas, as in Austin and Houston, people with the federally-funded housing choice vouchers, also known as Section 8, face a difficult search for housing that is both affordable and available based on a landlord's willingness to rent to them.

The 2015 law bars Texas cities and counties from enacting their own laws, often known as "source of income" ordinances, that would require landlords to accept the vouchers. By protecting landlords' ability to refuse vouchers, the lawsuits alleges, voucher holders -- who are predominantly black -- often wind up stuck in racially segregated areas. It's a pattern that advocates say plays out across Texas' largest cities, including Houston.

Supporters of the Texas legislation argue that local laws that might force landlords to accept vouchers would essentially force them into a federal contract. By doing so, supporters argued, landlords risk delays in payment and being subject to complicated HUD legal guidelines.

"The voucher program is one of the biggest programs," explained Tory Gunsolley, president of the Houston Housing Authority, at an affordable housing symposium sponsored by the Kinder Institute Friday, same the day the lawsuit was filed. "And you can't live in a voucher." He recounted that some families have to retur their vouches because they were unable to find an affordable place that would accept it. "Section 8 landlord discrimination is legal in Texas," he said, "and that's a huge problem."

Groups representing apartment owners have pushed back against housing advocates' efforts, arguing that source of income ordinances restrict landlords' right and add an undue burden of regulatory red tape. But the suit notes that Austin's ordinance, for example, did not limit landlords from denying a unit to someone, including a voucher holder, based on other legitimate business reasons. And other measures that protect renters from discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender and age, for example, have not been similarly struck down by the state.

"The voucher program is publicly known to be predominantly Black," the lawsuit states, noting that 87 percent of voucher holders in Dallas are black. "The households participating in the voucher program are subjected to various negative racial stereotypes."

Other parts of the country have had more success with source of income protections. Several states have enacted laws that prevent landlords from refusing to accept vouchers, as have roughly two dozen cities and counties including Los Angeles, Chicago (Cook County) and New York.

The plaintiff in the Texas lawsuit, the Inclusive Communities Project, is notable because it was behind another fair housing challenge that had national ramifications. That earlier lawsuit focused on Texas's system of awarding low income housing tax credits, which Inclusive Communities alleged were awarded in large numbers to black, inner-city areas and in few numbers to white, suburban neighborhoods. The case made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court in 2015, when the court upheld that housing policies that had a "disparate impact" on a particular group were in violation of the Fair Housing Act.

In the most recent lawsuit, the advocacy group argues that a local ordinance banning landlord discrimination based on a tenant's source of income would open more majority-white neighborhoods in Dallas to their clients who hold vouchers.

The lawsuit points to another complicating factor: It argues Dallas was required to consider enacting a source of income ordinance following a voluntary compliance agreement it entered with the federal housing department after it was found to be in violation of the Civil Rights Act, according to the filing. But because of the state ban, the city was unable to pass anything prohibiting landlords from discriminating against voucher holders.

In Houston, there are some 22,300 voucher holders with another 35,000 on closed waiting lists with the city and county housing authorities.

A family of four cannot make more than $33,300 annually to qualify for the program, and voucher holders typically contribute 30 percent of their income to rent, which can't be above a certain limit ($976 for a two-bedroom apartment), with federal assistance making up the rest.

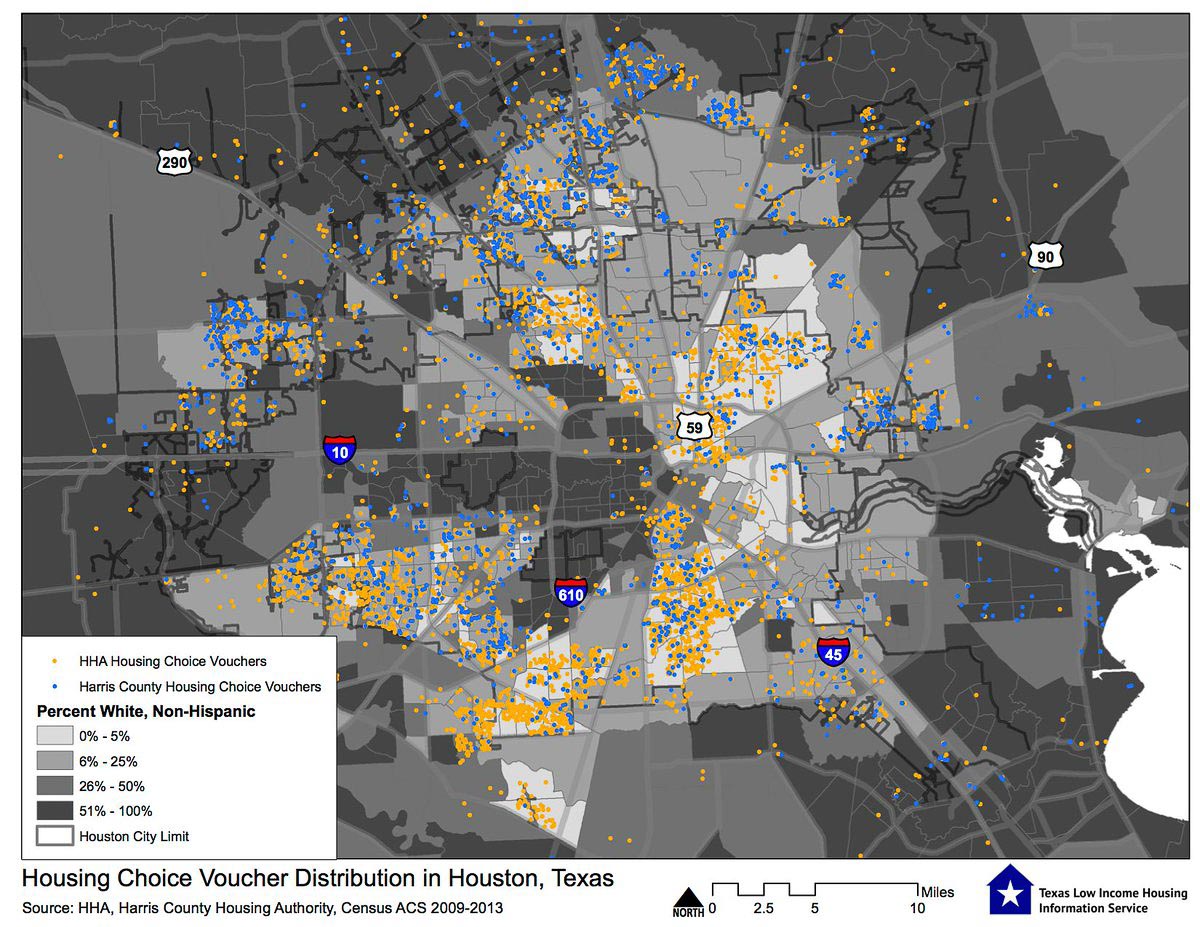

Like Dallas, most of the people receiving vouchers in Houston are black. Eighty-nine percent of the Houston Housing Authority's voucher holders, for example are black, according to the Houston Chronicle. But, as mapped by the Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, those voucher holders tend to end up in largely black or Hispanic areas with small white populations.