Last month the US Department of Housing and Urban Development approved the state’s General Land Office (GLO) State Action Plan for recovery and repair funds. The state received $5 billion, with $2.3 billion split between Houston and Harris County and the remainder left for other areas.

Those funds represent a concerted effort from Texas leaders who lobbied to secure them. The funds will be split between eight programs, headed by the GLO, with the largest (28 percent of the overall amount) going to help homeowners with “rehabilitation and reconstruction.”

This news was welcomed by many in the state and region, but a new report examining the process highlights significant problems that go beyond the current recovery from Hurricane Harvey and challenge our state and nation to rethink our approach to disaster recovery funding.

The shortcomings of the current funding system are both a burden to disaster-prone areas and a financial liability to the entire nation: by inefficiently allocating funds towards rebuilding rather than resilience building the system perpetuates and incentivizes negative behavior that leaves cities in stasis, increasing debt and needlessly risking life and infrastructure.

Previously, the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, in collaboration with the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M Corpus Christi, produced a primer on the disaster response and recovery, clarifying much of how the current disaster funding system functions. The current report responds and builds on the discussion by exploring the negative incentives the existing disaster funding system produces and how these adverse incentives undercut long-term mitigation efforts.

The report examines challenges in Texas for securing effective hazard mitigation planning and resilience building, highlights some of the major issues with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), and addresses the negative incentives created by the current disaster funding system.

Substantively, several of these approaches to improve the disaster funding system have largely been well-documented recommendations across several platforms and organizations. Indeed, the report underscores the ways in which Texas’ long-term hazard mitigation planning efforts have not been effective in preparing the state to deal with either disaster mitigation or the recovery process.

Hazard mitigation plans in Texas, largely, emphasize federal grant-funded projects --- not traditionally designed to be forward thinking or to build resilience. Instead of following the federal template, Texas leaders should reevaluate their approach to resilience building. Whether that approach necessitates additional funding or emphasizing roles in the disaster response and recovery framework is up to elected and community leaders.

The report covers several approaches to improve the current disaster funding system, including:

· Using collaborative entities to leverage the talent of the private and non-profit sectors during recovery;

· Creating regional disaster funding and recovery organizations to supplement federal programs;

· Explicitly delineating responsibilities between federal, state and municipal actors;

· Introducing a sliding-scale cost-share between the federal government and states instead of guaranteeing funds;

· Reforming NFIP, by introducing private competitors or introducing long-term insurance contracts with an explicit obligation to mitigate properties;

· Expanding the disaster bond market to provide greater liquidity in disaster funds.

The report details how these approaches would improve the system while offering examples of states and municipalities, namely in North Carolina, that have supplemented federal disaster funding and built robust hazard mitigation efforts.

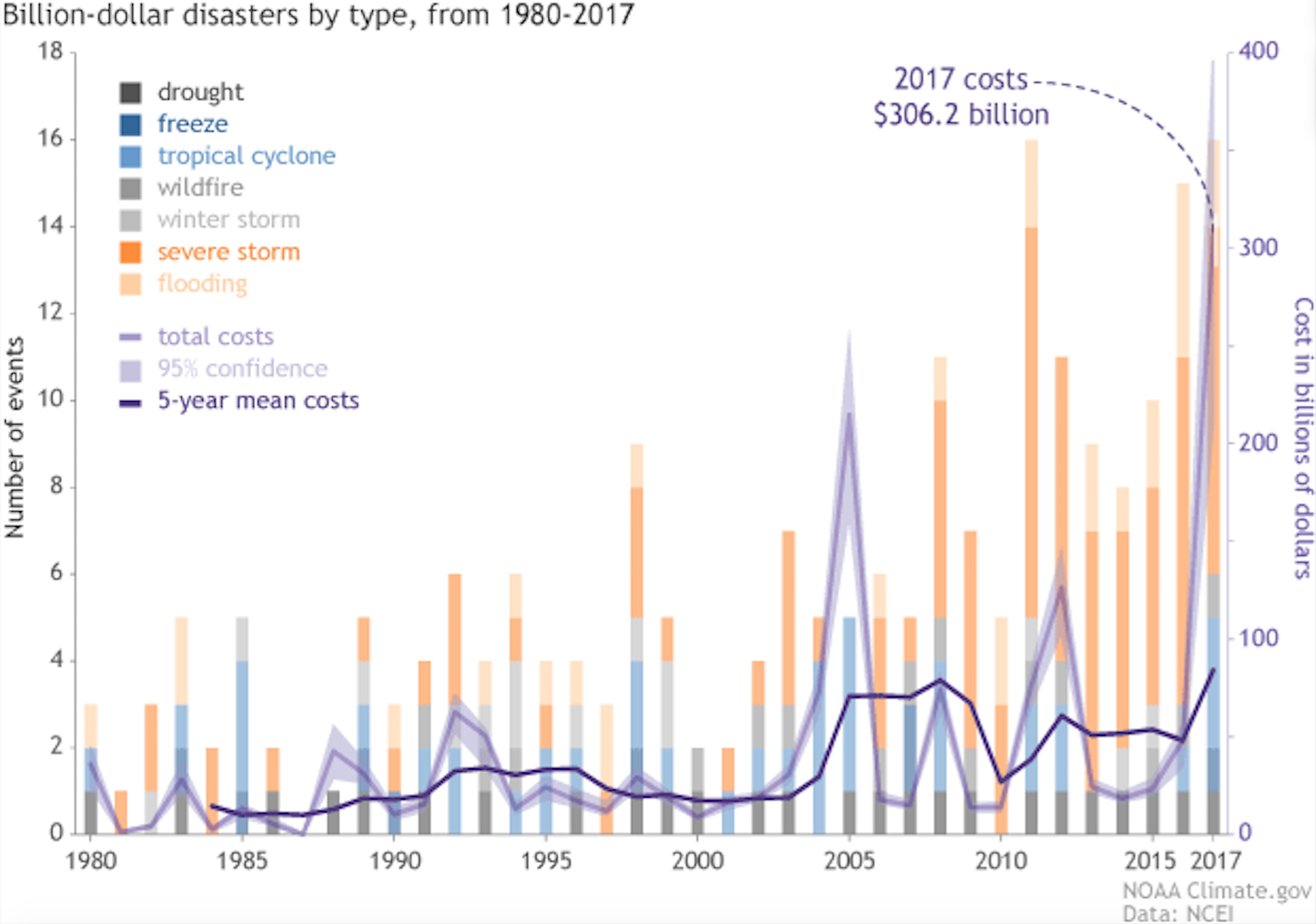

With national disaster costs continuing to rise, there is a strain on sources of federal funding. A string of storms in 2017 reflected an increasing trend of more frequent and costlier climate-related disasters. While climate disasters are largely unforecastable this does not mean we cannot expect more in the future. Whether we call it climate change or climate irregularities, the reality is the norm is to have more, and slower-moving tropical storms, like Harvey, that bring additional rainfall because of the warmer air and water.

It is imperative for Texas leaders to reevaluate their approach to resilience building.