On a recent tour through central London, Columbia University sociology professor Saskia Sassen overheard tourists praising the "wonderful British buildings," the shiny new icons of the city's skyline. But most of the skyscrapers on the tour, she said at a recent lecture at Rice University, are owned not by British businesses but by Chinese companies. In fact, a decent chunk of the urban London landscape is owned by foreign governments and companies. "The Qatari Royals, for instance, own more of central London than the Queen of England," said Sassen.

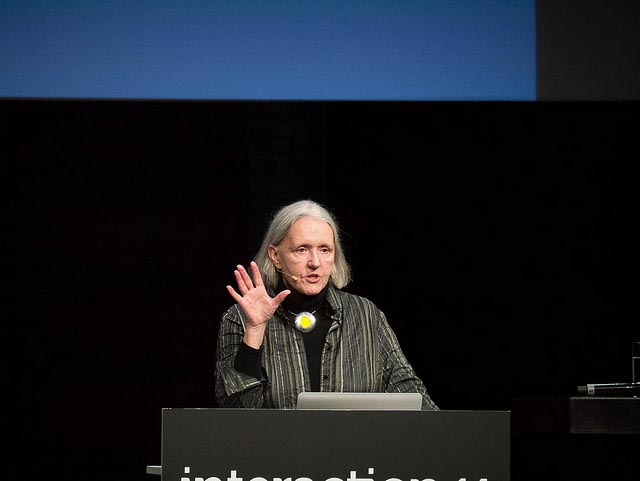

A leading expert on globalization and the author of several influential books including "The Global City" and "Civilization and Its Discontents," Sassen has spent decades examining how transformations in the global economy have reshaped places, like London, which she describes as global cities.

In some ways, her research describes the same sort of destabilization seized on by politicians like Donald Trump and Britain's Nigel Farage, Brexit-supporter and former head of the right-wing Independence Party. But where Trump and Farage take aim at immigrants, Sassen's ongoing analysis reveals a more systematic economic and geographic unsettling tied to currency speculation, deregulation of banks and the introduction of increasingly complicated financial instruments which incentive and result in unprecedented urban land grabs that are transforming how we think of urbanity and place.

"In London and New York," said Sassen, "everyone is aware this is happening."

In the United States, foreign real estate investment jumped after the recession. "Many players in recent years have been operating under much looser monetary conditions than in previous decades, so money has become cheaper, and opportunities have been presented in those countries where asset prices were hit by domestic recession," according to a report from Savills, a UK-based real estate firm.

Not only has the number of cross-border real estate deals grown, but the value has too -- from $65 billion in 2009 to $217 billion in 2015, according to the report, representing more than half the value of all global assets. The value, estimated at $217 trillion, is difficult to comprehend and far surpasses the world's GDP.

"The value is partly a result of the fact that it is financialized," explained Sassen, meaning it derives value beyond its material components through a variety of increasingly complicated financial instruments that tend to favor Western markets. Global cities, defined by Sassen as hosting the sorts of financial services that have fueled globalization, receive the most foreign investment. So London and Dubai are high on the list. New York and Los Angeles are as well. But as those markets get more expensive, the report said, Houston, Dallas and other Sun Belt markets have drawn attention from investors, even though a recent survey of foreign investors shows Houston has recently slipped from the top five most attractive U.S. cities in 2016.

Foreign investors in Houston are not just buying up existing property, like 1000 Main, bought by a German company, but also financing new construction, including a $70 million residential tower in the Galleria area, according to a commercial real estate blog.

But the kind of development this investment represents, argues Sassen, is problematic for cities facing increasing inequality. The same forces that have helped create a bifurcating global economy, with what Sassen describes as global elites on the one end and an increasing, often informal service sector on the other, is now fueling what she calls an urban land grab.

"Such a transformation has deep and significant implications for equity, democracy and rights," Sassen wrote in a column in The Guardian. The same thing, she notes, is happening in rural places as well, where companies buy up large quantities of land, only to displace farmers and exhaust natural resources.

In urban spaces, this trend can play out like a sort of hyper-gentrification. The elite spaces of Manhattan, argues Sassen, become more connected to the elite spaces of Sao Paulo than they are to a neighborhood in Queens. In those spaces, writes William Robinson, sociology professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, "neighborhood shops and eateries tailored to local needs are replaced by upscale boutiques and restaurants catering to the new high-income elite." This shift, Robinson explained in a review and critique of Sassen's work, has the effect of "high-income gentrification," that "rests on a vast supply of low- wage workers."

Not only are these spaces cost-prohibitive but they are financed in shadowy ways, operating well above the level of public input. The "towers of secrecy" as the New York Times called the skyscrapers that host the shell companies funneling foreign money into real estate, transform cities without much responsibility to the people living there.

In some ways, Sassen argued, this upends our very understanding of urban spaces as a sort of meeting ground. Though that narrative glosses over the segregated history of cities, these land grabs represent a significant shift in ownership of the city.

Though they are still dense, skyscrapers full of shell companies do not really qualify as urban, she argues. "The city -- the really working city, not just concentrated buildings -- is a space where those without power get to make history, get to make modest economies, get to make cultures," she said.

And that, she argued, is what is at stake in an increasingly secretive, financialized global economy -- something a border wall has little to do with.