As Houston confronts an unfunded pension liability of nearly $4 billion, city leaders are working to try to figure out how they can climb out from that hole.

The good news? For Houston -- and almost any other city in a similar predicament -- there are clear, identifiable steps that can be taken to restore the financial health of the pension system.

The bad news? Each of those steps can cause political or financial pain for a variety of stakeholders.

The Kinder Institute's newest report, "The Houston Pension Question," explores how the city's unfunded pension liability grew so large, so fast. But just as importantly, it outlines actions the city can take to address that challenge.

Importantly, the Kinder Institute doesn't offer a specific policy prescription for the city. But it identifies key steps that may improve Houston's pension finances, based on a financial analysis of Houston's pensions, as well as a rigorous study of other cities' pension reform efforts.

A combination of some or all of the following steps will almost certainly be necessary if the city seeks to make a dent in its $3.9 billion liability.

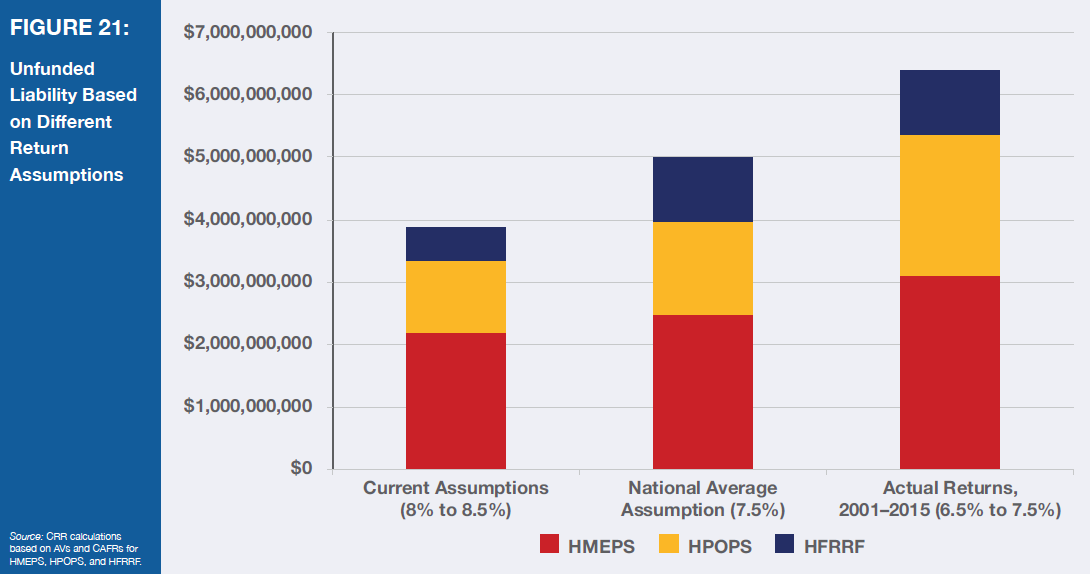

Changing assumptions and methods associated with the pension plans. Since 1992, each of the city's three pension plans has assumed a rate of return on its investments of 8 percent to 8.5 percent. From 2001 to 2015, however, they all earned less than that (the municipal workers' plan, for example, earned a 6.25 percent return). When returns fall short of expectations, a pension system's unfunded liability increases (as we discussed previously). The systems would benefit from using investment projections that align with the plans' recent financial performance.

Similarly, the city uses what's called a "rolling amortization" schedule that effectively resets the clock on its annual pension payment schedule annually. Essentially, it perpetually backloads the largest payments the city must make to the pension plans to a day that will never actually come. As a result, the liability will never be fully paid under the status quo. Several cities, including Phoenix and Baltimore, have had success switching to a "closed amortization schedule" -- or essentially, a commitment to fully pay the unfunded liability with a specific period of time, generally 20 to 30 years. Such a step could also help Houston shrink its liability.

Unfortunately, both of these options come at a cost. The chart below shows what happens if the pension plans made more conservative projections of their investment returns. The size of the unfunded liability goes up -- in some cases, quite dramatically. That, in turn, would increase the payments the city must make annually to keep the pension systems funded.

Via Kinder Institute

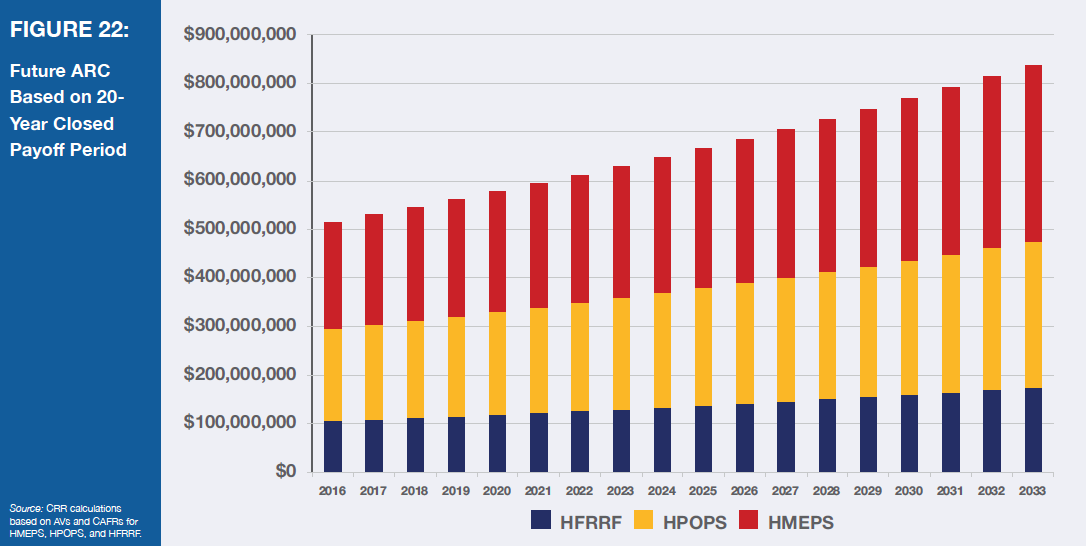

And this graph shows what happens to the city's annual pension payments if Houston decided to commit to paying off its unfunded liabilities in 20 years. For context, its Annual Required Contribution -- the amount it must pay to keep the pensions adequately funded --was $400 million 2015 (though it only paid $350 million).

If the city switched to a 20-year closed amortization schedule, as other cities have done, its annual payment in 2017 would be $500 million, and it would grow to more than $800 million before the unfunded liability is paid off in the 2030s.

Via Kinder Institute

To pay for these increased costs, the city would need to increase its revenue -- possibly by repealing its revenue cap and increasing property taxes -- or divert funds from other public uses. Those types of moves are unlikely to be popular with city taxpayers (or with lawmakers, for that matter), but ultimately, they may prove to be necessary.

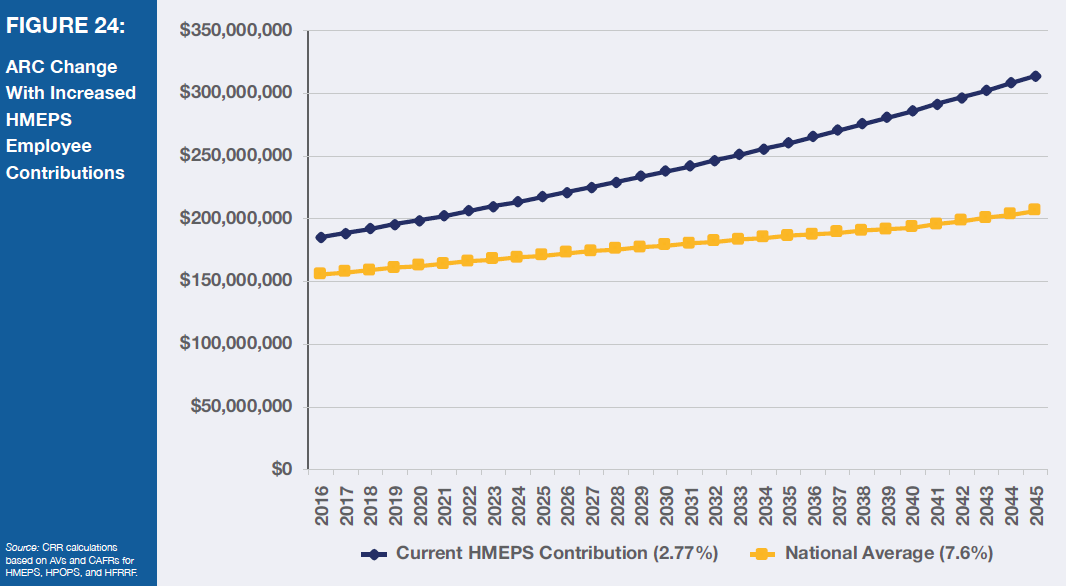

Employees increase their contributions to the pension systems. The study shows that participants in the Houston municipal workers' plan contribute 2.77 percent of their city income to their pensions. Nationally, participants in large local plans contribute at almost three times that rate -- 7.6 percent. Several cities have increased employee contributions as part of their pension reform efforts. It may be logical to do this in cases where employees contribute less than their peers nationally. But effectively, this would reduce employees' total compensation, potentially making Houston a less competitive employer.

The graph below shows what would happen to the city's Annual Required Contribution if the city's municipal workers started contributing at the average level for public employees nationwide. The savings are immediate, and they grow annually. By 2025, the city would be saving $100 million annually on pension contributions.

Via Kinder Institute

Switch to a defined contribution system or a “hybrid” defined benefit/defined contribution system for new hires. This step can help slow the growth of the pensions' unfunded liability because it shifts financial risks from the employers to employees. Eventually, most employees would be on plans that are similar to a private sector 401(k), in which the employer is not responsible for guaranteeing a certain retirement benefit. The technique has been used in places such as San Diego and Fort Lauderdale as those cities worked to manage pension costs.

Because this technique doesn't pay off previously-accrued liabilities, it can take many years for the city to enjoy the financial benefit of this move. However, it offers a big upside for some employees: defined contribution plans are more portable than traditional pensions, so they're potentially more attractive to shorter-term and younger workers.

Reduce benefits for current employees. Generally, cities are legally prohibited from simply cutting benefits for current and former employees. They have some flexibility, however, with annual Cost of Living Adjustments (COLAs) and reforms to Deferred Retirement Option Plans (DROP), which allow retirees to claim pension benefits while continuing to work.

Today, most Houston retirees receive an annual COLA of 2 percent to 3 percent. Reducing that annual COLA to 1 percent for current and future plan members would produce savings of $90 million in the first year, growing to $474 million in year 30, according to a 2014 study by Retirement Horizons Incorporated that was commissioned by the city. Freezing DROP credits could save $66 million in the first year and $355 million by year 30, according to that same analysis. But these reforms could be controversial because they also effectively reduce total employee contribution and increase the likelihood that retirees may lack sufficient retirement income.

All of these options can be part of a solution. And all of them are painful.

Taxpayers may have to pay higher taxes or enjoy fewer services. Retirees may face lower benefits. Current employees may face higher contributions, while future employees may have reduced benefits, and potentially, may lack the type of guaranteed pension that exists today altogether.

The city, its employees and taxpayers will have to figure out which combination of options will work best for Houston. There is no silver bullet, and it will take the implementation of several steps to actually address the problem meaningfully.

But one thing is certain: if none of these reforms is adopted, and the status quo remains, there's nowhere for the unfunded pension liability to go but up.