Always own land. That was one of the lessons Edwin Harrison’s grandfather, who built their family’s home at the corner of Reeves and Burkett streets in Third Ward, taught him.

“You’ve got to have land in America because that’s what this country is built on, on property ownership,” he said. “That’s the way white folks set it up.”

Though his grandfather would later move to Meyerland and other Houston neighborhoods, Harrison’s family returned. His youngest son now lives in one of the homes his grandfather once owned and Harrison, now in his 60s, lives off Southmore Boulevard.

This is what he thinks about when he considers the change spreading across Third Ward. Gentrification. As much as the term is about change, it’s now become a constant in conversations about neighborhoods like Third Ward, historically black and Hispanic areas, close to Houston’s downtown that have attracted townhome developers. When a multimillion dollar renovation was finally unveiled at the historic Emancipation Park, neighbors wondered: will this hasten gentrification? As the University of Houston grew and expanded its student housing footprint into the neighborhood over decades, residents asked: what about us?

The concerns are justified. In the portion of the neighborhood closest to downtown, which includes Emancipation Park, median home values increased 176 percent between 2000 and 2013, according to an analysis of census estimates conducted by Governing.

There have been several interventions meant to curb the tide and create affordability. Federally-funded, city-administered down payment assistance programs, coupled with the city’s Land Assemblage Redevelopment Authority that took vacant tax delinquent property and sold it cheap to developers who agreed to produce homes at affordable price points. Low-income housing tax credits are responsible for the Houston Housing Authority’s first new development in a decade that opened recently in Independence Heights.

In Third Ward specifically, community development groups like Row House Community Development Corporation and the recently announced PRH Preservation, Inc. are dedicated to providing and managing low-income housing. And then there are the efforts of state representative Garnet Coleman, who through several quasi-governmental agencies, has helped amass land in the neighborhood, converting several to affordable housing with more in the works.

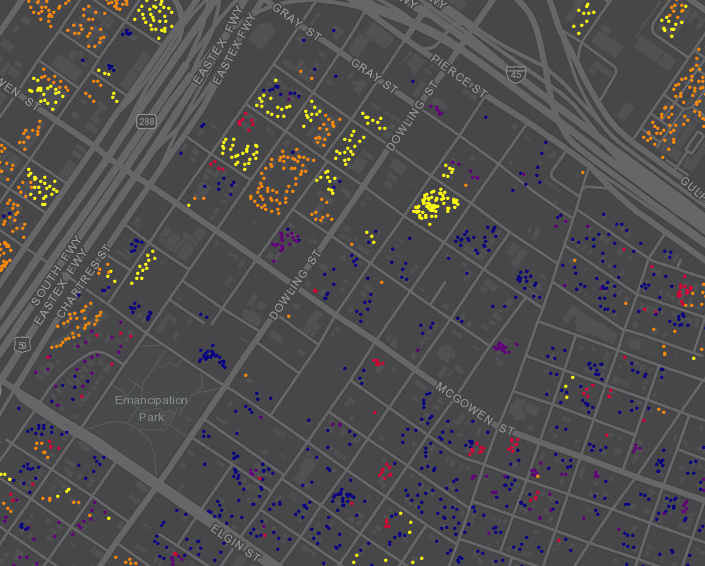

From the Kinder Institute's 2017 Taking Stock report, the map shows housing units by the year they were constructed. Properties shown in orange were built between 1985 and 2008, while those in yellow were built between 2009 and 2015, showing the new construction dotting the area around Emancipation Park.

In a state that’s often hostile to city-led efforts to create or preserve affordability, those efforts are not insignificant.

But more is needed, argue neighborhood advocates. Something that doesn’t just provide subsidies for affordable homeownership but that changes the game entirely.

So as the City of Houston set about creating its own Community Land Trust (CLT) with the aim of making homeownership affordable, Third Ward was among the neighborhoods watching with particular interest. A land trust promised to be different from the city’s past affordability programs in several ways, not the least of which was longer term affordability. In a typical community land trust, according to a document prepared for the city council back in December 2016 by the Grounded Network Solutions organization, “the typical land lease agreement between a CLT and a homeowner has a 99-year term, can be inherited, and can be renewed at the end of the first 99-year term for an additional 99 years.”

But there’s a lot of variability in how trusts can function, even within the state’s requirements. The city’s, for example, will be citywide while in many other cases, they focus on a particular neighborhood. And the nonprofits can be used for residential or commercial purposes but generally focus on affordable housing, whether through homeownership or renting.

That’s where the proposed Third Ward community land trust comes in. Among the goals in the far-reaching draft plan for the neighborhood created by the mayor’s Complete Communities initiative is the creation of a community land trust. Independence Heights, another historically black area just outside the Loop also confronting neighborhood change, has also explored the idea of a community land trust, conducting a study in 2017 to assess current ownership patterns and establish the level of interest among residents.

“We recognize there are communities that may want a community-based CLT and we fully support that,” said Tom McCasland, head of the city’s housing department.

With the experience of LARA, which proved to be a somewhat sluggish effort that produced homes that even a city employee sometimes found out of reach, the city has many of the resources to launch something like a land trust. McCasland estimates that the effective subsidy a homebuyer could receive would increase from the current amount the city helps fund for qualified buyers to around $50,000 or $60,000.

But the effort in Third Ward would involve creating something new. And radical.

A radical proposal

“The difficulty here in Texas and in Houston is that we really place a high appreciation on the commodification of land,” explained Jeffrey Lowe, an associate professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University and a Kinder Fellow. “Many of our policies basically promote private property ownership, not only that the land should be commodified, but that it should be commodified to its maximum value.”

That’s not to say there aren’t community land trusts in Texas. There are, the most productive of which, in Lowe’s estimation, is Austin’s Guadalupe Community Land Trust, run by the neighborhood development corporation. But there aren’t any active neighborhood land trusts in business-friendly Houston. So while there are several steps involved in creating a neighborhood land trust, including incoroporating as a nonprofit, establishing bylaws and governance structures, receiving a designation from the city and seeking certain tax exemptions, getting community buy-in is a large part of the process.

“It’s a values question,” said Lowe. “The CLT model is one that does not lend itself to the maximum that the market can bear, it lends itself more to giving away the maximum in a way that those who need assistance the most, those persons who are lower-income, for example, have an opportunity to have shelter that they can afford.”

In addition to providing affordable rental housing, Austin’s Guadalupe Community Land Trust, for example, works with homebuyers whose incomes are at or below 80 percent of the area median income and many of the folks it serves are well below that. In 2017, 80 percent area median income amounted to $52,100 for a two-person household and $65,100 for a four-person household. The group also prioritizes households that have “long-standing ties to East Austin.” Between 1984 and 2018, the land trust grew from seven to 60 homes, according to the organization’s latest annual report. Families buy the homes, sold well below the market value, and lease the land itself from the community land trust. That way, the homeowners pay taxes just on the house, not the property.

Community land trusts are also set up to create longer-term affordability, meaning rents remain affordable to a target population and if homeowners sell, for example, there are measures to make sure the money returns to the land trust to continue to subsidize affordable homeownership.

There are ways that homeowners could stand to benefit from rising values. In the City of Houston’s land trust, for example, there could still be opportunities for wealth creation.

“If you have your resale formula set properly, the resale price of the home is growing hopefully at or about the rate of income growth for your target population, said McCasland. Say a $150,000 home increases in value to $170,000 over 10 years. If the homeowner sells, “they homeowner gets the $20,000 upside,” said McCasland, plus whatever equity they put down when they purchased the home. With that formula, the community land trust can ideally sell the home at the new price point and it would still be considered affordable. If not, the trust would have to add more subsidy into the home. “The goal is to balance wealth creation with affordability in a land trust model,” he said.

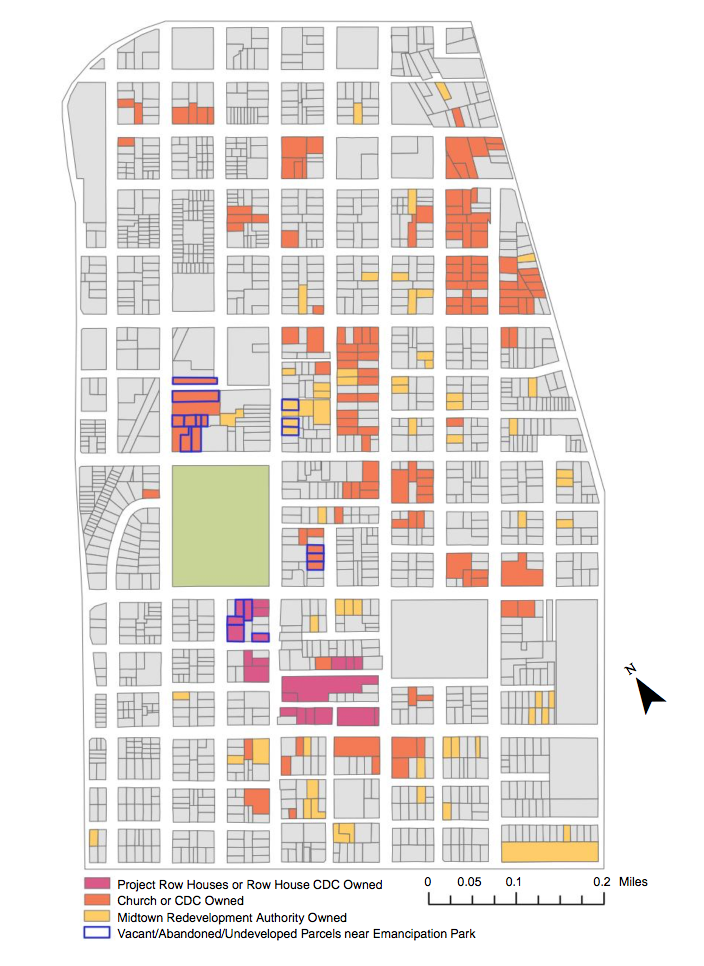

A map of landowners around Emancipation Park, prepared for a 2016 report by the MIT Department of Urban Planning in collaboration with the Emancipation Economic Development Council.

Third Ward’s Emancipation Economic Development Council has been mobilizing around the idea that, in the face of gentrification, the neighborhood needs its own community land trust to ensure residents at risk of displacement can stay in their neighborhood. A partnership with the MIT Department of Urban Planning back in 2016 helped lay the groundwork for plans there for a community land trust. That effort identified the area around Emancipation Park as one well-suited to a land trust. Key to realizing that goal, however, would be existing landowners in the neighborhood working together to make that land available.

“The strength is the community owning the land and allowing homeowners, long-term residents to have a say in what happens to their land,” said Shanette Prince, community coordinator of the organization that brings together residents, businesses, churches and other groups across the neighborhood. "Residents [would] have a say in what happens to their land long-term," she said, and would be "able to collectively organize that land and make sure that the land is used in the way that the community wants the land used."

Deep roots, high hopes

The promise is high. It could mean increasing affordability, avoiding displacement and creating secure and safe housing. Beyond that, Lowe said some models, particularly those that prioritize neighborhood control, can actually foster democracy and serve as a platform for grassroots organizing more generally. “It’s a platform that helps build human social and political capital,” he said.

Across the country there are more than 220 land trusts. They vary in size and location but tend toward the coasts. There are urban land trusts and rural land trusts. The movement has its roots in the Civil Rights era, Lowe explained, when it offered a particular promise to black Americans who saw in them the potential to mitigate the unequal structures and policies that kept them from participating in society in the same way as white Americans. Homeownership was just one of the avenues to wealth creation and neighborhood stabilization that many black families were excluded from and in the rural South, land trusts, like New Communities Inc. in Georgia, also offered a route to stability as a way out of sharecropping.

A community land trust represented the opportunity to undo hundreds of years of dispossession.

Instead of representing a loss of ownership, the land trust provided the opposite.

The movement grew slowly until the mid-'90s, when the number of land trusts grew significantly, roughly doubling over a decade.

Many of those barriers to wealth creation that some early supporters of land trusts identified persist today. A recent study of the Harris County Tax Appraisal District, for example, found that race and neighborhood demographics were significant factors in valuing homes, all other things held equal. Even with homeownership, the potential wealth black neighborhoods can create from their homes has been suppressed.

During that same period when land trusts took off, gentrification, a term that’s been around for about as long as the community land trust here, tightened its grip on cities across the country. Between 1990 and 2000, 8.6 percent of census tracts eligible to gentrify, meaning the median household incomes and values were already above a certain level, were in fact gentrifying, compared to 18.4 percent since 2000, according to Governing’s analysis. Several of the census tracts included in the Greater Third Ward area were among those gentrifying in the analysis.

“To me, it’s all about the speed of change,” said Shannon Van Zandt, head of the department of landscape architecture and urban planning at Texas A&M University. Co-author of a recent study on community land trusts and gentrification, Van Zandt said, “You want things to be increasing in value but slowly enough that incomes can keep up with increased taxes.”

Along with Myungshik Choi and David Matarrita-Cascante, Van Zandt found that the presence of a community land trust did seem to stabilize housing values in census tracts that were gentrifying between 2000 and 2010. “What’s important about that is that it slows the rate of gentrification,” she explained. The presence of a community land trust decreased the odds of gentrification by 70 percent, according to the study, in the full sample model when all other factors were held equal.

There were other findings, some that were harder to explain, including that tenure among residents actually didn’t change in gentrifying neighborhoods with CLTs or in non-gentrifying neighborhoods, but, counter to much of the current wisdom, the length of residency actually increased in gentrifying neighborhoods without CLTs and non-gentrifying neighborhoods with CLTs. That finding is a bit of a puzzle to Van Zandt. One possible explanation could be “kind of a stubbornness or digging in.” Qualitative studies, like one from the University of Texas that looked at the effects of gentrification on longtime residents who stayed, have shown that displacement is just one of the possible negative impacts on existing residents.

Still, the overall conclusion Van Zandt draws is that community land trusts can offer a way for neighborhoods to mitigate gentrification and provide genuine options about staying or leaving. “You want people to have choices and you want them to be able to make the choice,” she said.

“It’s neighborhood revitalization that would fit into a public policy that ensures that those who need the help the most benefit,” said Lowe. “In my opinion, that’s the greatest challenge here in Houston because we do not have [that] public policy in place.”

A tough sell

As the executive director of Row House Community Development Corporation, Harrison oversees, among other things, the organization’s affordable housing program in Northern Third Ward. “We provide housing for low-income individuals but everything we do is rental because 75 percent of the people who live [in the area] rent,” said Harrison. He sees that need on a daily basis.

He also sees just how hard it can be to get the subsidies needed to provide truly affordable housing. “You need a great deal of subsidy to really help people that are living in areas like the Third Ward because of the rapid increase in property values,” he said. For Row House CDC, for example, the county offers a tax rate break and it values the organization’s low-income rental housing based on the cash flow it derives from those properties, which is significantly less than the property could be generating at market value.

Row House CDC properties, which Harrison credits the creation of to "Coleman's leadership." Source: Row House CDC.

Those properties were made possible thanks to Coleman’s maneuvering. For years, the state representative has been orchestrating land purchases through the Midtown Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone (TIRZ) and its related Midtown Redevelopment Agency across the neighborhood. He estimates the value of all the land the agency has amassed is around $72 million.

“We were buying land quietly. This is how you do it,” he said. “My family has been in this Third Ward area for 100 years,” he added. “I know my constituents. We’ve done plans before. The first Third Ward redevelopment plan was done in 1993.”

From Coleman's perspective, the TIRZ has acted as a de facto land trust, assembling land and developing it to be affordable. He’s supportive of EEDC and efforts to create a formal land trust in the neighborhood but he sees it as working parallel to his work for the most part.

From the outside, the maneuvering of so many quasi-governmental bodies can feel slow and distant. But Coleman said that’s part of the reality of producing affordable housing. “We’re transparent, all that land we purchased had to be on an agenda of a public entity,” he said. There is a sort of master plan for the Midtown properties, he said, but, “it hasn’t been released,” yet.

Like Harrison, he sees a role for a community land trust, but has reservations as well. For one thing, he said he's less interested in homeownership and more so in low-density rental housing. For another, he’s still not sure folks will embrace the model. What happens, he mused, when “grandchildren walk in there and think it’s their house and it turns out to be not really their house.” Under the community land trust model, the house is theirs but not the land, which might not be what the exact arrangement they were expecting. Still, as McCasland explained, the opportunity for wealth creation is still there, even if the land itself is leased.

Then there’s all the work already being done. “We’ve been working on it for 26 years,” said Coleman. “That’s when the Third Ward Redevelopment Council was created and out of that came Old Spanish Trail/Almeda Corridors TIRZ and Houston Southeast Management District. I passed the bill for Houston Southeast.” Indeed, Harrison credits Coleman’s leadership for supporting what affordable housing there is in the neighborhood now.

All of these efforts, so dependent on government, don’t offer what community land trusts do, argued Lowe.

Complete Communities, while well-intentioned to target resources to long under-served neighborhoods, “is just an initiative,” he said, “it is not a policy intervention.” The various strategies available now for financing affordable housing are, in the end, market-oriented. “For example, we do not have a housing trust fund. We do not have inclusionary zoning,” said Lowe. “What a community land trust model would provide [is] an alternative…it could be, I argue, here in Houston, a major policy intervention that would begin to ensure that lower income residents benefit from neighborhood change.”

And that would be radical. Coleman’s hypothetical grandchildren example, for instance, would have to be confronted. “You’ve got a trust issue,” Harrison said. In thinking about the city’s land trust, McCasland emphasized that expectations would have to be very clear for any potential buyers. “The land trust needs to set the expectations with the homebuyers,” he said, “They need to be the person looking them in the eye saying, ‘you’re not buying a regular home here, here are your restrictions.’”

That, said Lowe, might be particularly hard to do in Houston. “Here in Houston, people like the idea of an approach where lower-income people benefit,” he said, “but when it comes to implementing it, it’s so far out of the realm of what they’re used to…that it’s very difficult for them to accept the community land trust approach.”

What it comes down to, then, is a matter of values, like Lowe said. “Community revitalization has not been our focus,” said Lowe. Instead “it has been primarily the redevelopment of places where market approaches benefit those who already have the means. The community land trust is an alternative approach to that while at the same time it could help advance democratization” and grassroots organizing, he explained. “If we believe that’s important, then we have to think of ways of building it back.”

The post has been updated to include the correct title for Jeffrey Lowe, an associate professor at Texas Southern University, and to clarify how community land trusts work with regard to multiple generations.