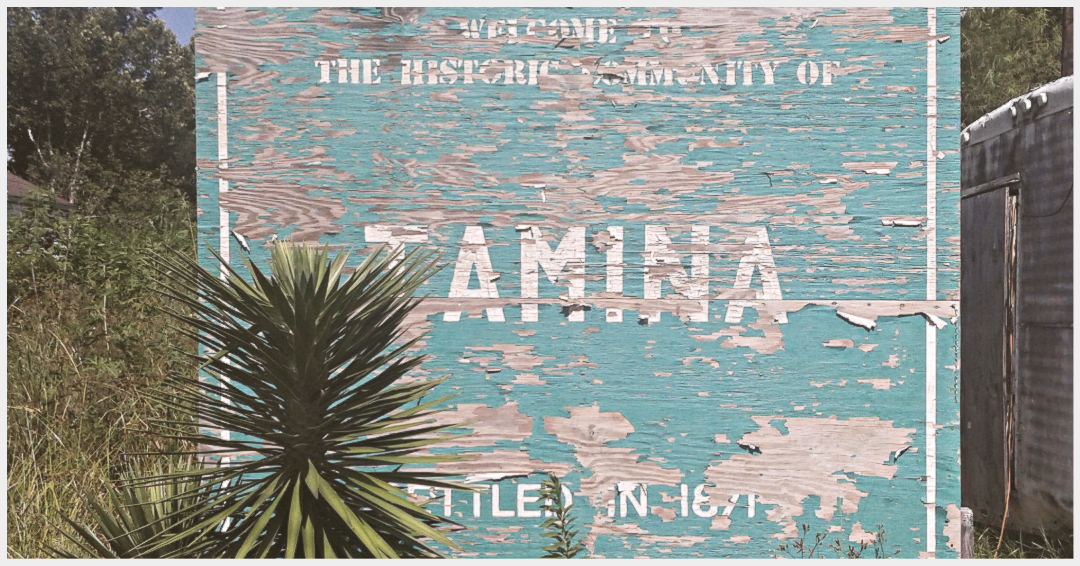

Shenandoah’s approval in late December was the final step in an agreement to install new water and sewer lines in Tamina. The sewer service will replace aging septic systems that have created health hazards and inhibited growth in the unincorporated community, which was founded by formerly enslaved people in the 19th century.

Like most difficult deals, though, this one involved compromise. Federal rules required that a municipality receive the $21 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds to pay for the new infrastructure. The Old Tamina Water Supply Corp., which has overseen water service in Tamina for many years, is a nonprofit organization; it didn’t qualify. This means that the nonprofit will have to turn over a document known as a Certificate of Convenience and Necessity, which it acquired from the state in 1989, to Shenandoah. In the past, Tamina residents had resisted similar agreements because they feared a loss of autonomy. But this time, Leveston said, he and his neighbors took a more pragmatic view.

“I wasn’t exactly satisfied with the way some of the things worked out; we still end up signing our CCN over to Shenandoah,” said Leveston, 79, who has learned the relevant bureaucratic lingo during his years of leading the water supply corporation. “But it didn’t seem like we were ever going to get federal funds any other way. We had tried every avenue. We had to fight tooth and nail for everything.”

Tamina’s dilemma is unusual but not unique. A 2018 Kinder Institute report found that about 400,000 Harris County residents are not part of a city or of a municipal utility district (MUD) — special districts created at the outset of a new development — and thus receive few services.

In East Aldine, a largely Hispanic community just 14 miles north of downtown Houston, a management district has taken on the task of converting thousands of homes from water wells and septic systems to municipal-style utility service. Houston passed over the area during its aggressive annexation program in the 1980s, leaving East Aldine as an unincorporated island surrounded by a growing city.

An evaluation in the 1990s revealed that more than 4,500 single-family homes in East Aldine relied on shallow, private water wells and septic systems. Using federal grants and management district funds from sales taxes, the East Aldine Management District so far has provided some 1,300 sewer connections and about 400 water connections, said Scott Bean, director of public infrastructure.

The project has been challenging, he said, because the available federal programs disburse funds in small increments. “We’re down to doing it street by street now because we can only get about $1 million a year,” Bean said.

Richard Cantu, the management district’s executive director, recalled hearing from a woman whose street had recently received a sewer connection. Her property included a large side yard, Cantu said, but it was often contaminated because of frequent overflow from the septic system.

“She told me, ‘We are just so happy that our kids can play in the yard now,’” he recalled.

There’s no management district in Tamina, a low-income community surrounded by prospering suburbs such as The Woodlands and Oak Ridge North. The lack of a modern sewerage system has been a huge obstacle to new development. Septic systems are a logical option in sparsely populated rural areas, but they require a lot of land — a minimum of one-acre lots in Montgomery County — and aren’t suited for denser suburban development patterns.

Until around 1970, Tamina didn’t even have running water. Before that, residents obtained water from a communal artesian well. “They had the neighborhood water man who would put barrels on his truck or wagon and take it to people’s homes,” Leveston told me for a Houston Chronicle article in 2018.

In recent decades, the neighboring community of Chateau Woods has sold water to Tamina. The water is stored in tanks and pumped to homes; the nonprofit run by Leveston has administered the system and handled billing. Under the new agreement, those duties will be turned over to the city of Shenandoah.

This was a bitter pill for Leveston to swallow. Decades of fighting for public services have left him and other community leaders distrustful and eager to cling to anything that represented Tamina’s identity and history. (Leveston, like many longtime residents, refers to the community as “Tammany.”)

“Tammany been here since the 1800s, before anything was out there. The only thing we had in Tammany was the water company, and we were trying to hold on to that,” he said.

Tamina, he said, was the last Montgomery County community to get paved roads or a public park. “We had to go to Commissioners Court three or four times to get a stop sign,” he said.

Ultimately, he said, his support for the new deal came down to a simple reality: “You have to give up something to get something.”

Mike Snyder is a Houston-based journalist who worked for more than 40 years as a reporter, editor, and columnist for the Houston Chronicle.