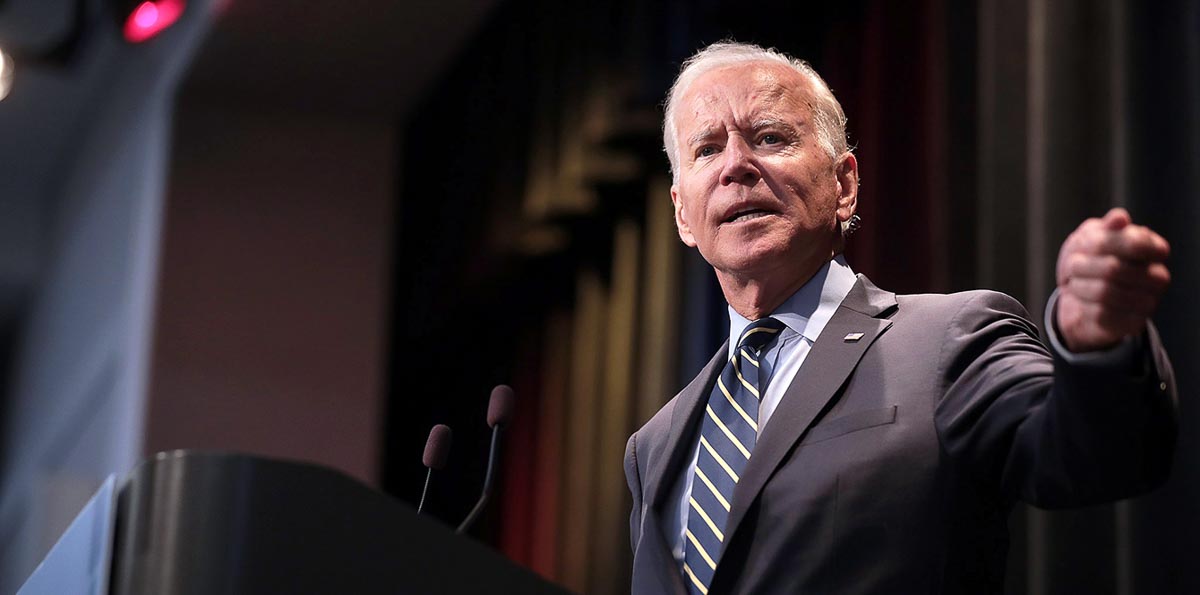

Even though Donald Trump lived in a high-rise mixed-use building in a big city for more than 30 years (Trump Tower), cities didn’t do well under the Trump administration. Joe Biden, on the other hand, is an unabashed urbanist. For example, he’s a guy who made the 90-minute commute between Wilmington, Delaware, and Washington, D.C., some 8,000 times during his 36 years in the Senate.

So, how will cities and urban life fare under a Biden administration?

The answer, almost certainly, is a lot better than they did under the Trump administration. Biden will make some short-term moves and then he will probably focus mostly on transportation and infrastructure, though he may make some moves on housing as well.

Short-term moves

Almost the first thing Biden did after he was sworn in on Wednesday was extend the federal eviction moratorium until March. This took the pressure off of a lot of local governments that have been struggling with this issue. But it doesn’t solve the larger problem of how, sooner or later, renters actually pay rent to landlords. That will probably be part of the $2 trillion or so coronavirus relief package, which will be Biden’s first order of business with Congress.

Transportation and infrastructure

The Trump administration never got an infrastructure package done — in fact, the ever-delayed “Infrastructure Week” was kind of a running joke. But Biden seems serious about infrastructure — the word is that after coronavirus relief, infrastructure will be his highest congressional priority, that he wants to get it done by July 4 and that it also will be somewhere in the ballpark of $2 trillion.

“Infrastructure” covers a lot of ground, of course. But transportation — and especially urban transportation — is likely to be a focus of his efforts.

Biden is known as a public transit supporter, in large part because of his experience with Amtrak. And transit agencies around the country are in deep trouble. On the one hand, they lost most of their riders during the pandemic — and a lot of their revenue, both from lost fares and a drop in retail sales, because sales tax supports public transit service in many cities (including Houston). But on the other hand, transit agencies have carried low-wage essential workers throughout the pandemic. The recent coronavirus relief bill gave transit $14 billion — about half of what the agencies say they need — and Biden’s coronavirus package is likely to contain more.

It’s unclear whether Biden will try to increase the gas tax — and whether he’ll try to change the highway/transit split on gas-tax funds. The federal gas tax is about 18 cents per gallon — but it hasn’t gone up since the early ‘90s, meaning it has lost almost half its value. For the past several years, the federal government has borrowed money from the general fund (which runs a big deficit) in order to replenish the transportation fund. But a gas-tax increase is just about the least popular move anybody could make.

But Biden may make a change that transit advocates are championing: Changing the long-standing 80/20 gas-tax split between highways and transit. This too has been a nonstarter in the past because the highway lobby in Washington is so strong, so Biden’s willingness to take it on — and basically rescue public transit or let it go down the tubes — will be a pretty important signal to cities nationwide.

One final question on highways important to Houston: Pete Buttigieg has already indicated that he will prioritize tearing down urban freeways, especially those that harmed neighborhoods of color. What does this mean for Houston’s I-45 project — if anything? On one hand, the project proposes to abandon the Pierce Elevated. On the other hand, the I-45 project is getting major pushback because of its impact on historically Black Independence Heights. Will Buttigieg’s impulse force TxDOT to rethink the project? Or will it go forward without pressure or influence from the federal government? It’s hard to know how deeply Buttigieg’s approach here will cut into the way state transportation departments, including TxDOT, do business.

One last transportation item is high-speed rail. The Obama administration made an important financial commitment to starting a national high-speed rail system and Trump backed off. As an Amtrak buff, it would seem logical that Biden would champion high-speed rail. But it’s hard to know if this would help Texas. The Texas Central high-speed line from Houston to Dallas is supposedly privately financed, and state Republican leaders have not been warm to financial subsidies.

Housing

The federal government plays an important role in supporting private-sector mortgages for home purchases and in providing funds for affordable housing. But overall housing production has been a problem nationally, especially in big cities, because of citizen opposition to new housing — and increasing private housing production through federal action might be a bipartisan issue that could get through Congress.

Biden might try to propose to Congress that increased funding for affordable housing be increased through added appropriations for both low-income housing tax credits (as was done in California under Gov. Gavin Newsom) and housing choice vouchers. The tax credits mostly go to affordable housing developers, who sell them to raise capital to build new affordable housing projects. The vouchers go to individual low-income tenants, who can use them to rent apartments at a subsidized rate. (You can read about the Kinder Institute’s past research on housing vouchers in Houston here.)

More controversially, the Biden administration will almost certainly try to revive the Obama-era Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule, or AFFH, which among other things required local governments to look at — and make plans to overcome — housing discrimination and segregation. The rule was, in part, a response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, Inc., which beefed up the obligation of local governments to consider placing affordable housing in affluent neighborhoods. It was the AFFH rule that President Trump was talking about when he said that Biden would “destroy the suburbs” if elected.

Finally, there’s the question of whether the federal government has a role in discouraging anti-growth zoning and encouraging more private housing production. Dating back to the Bush 41 administration, the federal government has sought to remove regulatory barriers to housing production — but those barriers are mostly put up by local governments, not by the feds. One idea that’s been kicked around in recent years is to somehow tie federal funding for housing to zoning reform by local governments so that it’s easier to build housing. This is an issue with some bipartisan support, though it’s vulnerable to Trump’s “destroying the suburbs attack” But it raises the question of whether withholding housing funds from cities that don’t want to build housing is a winning policy.

One day after Biden’s inauguration, it’s hard to know what, for sure, the new administration is willing to go to the mat for. But there’s no question that cities will be a higher priority than they were under Trump.