There were zero (as in none) cyclists or pedestrians killed in the Norwegian capital of Oslo in 2019. That’s a huge accomplishment for a city serious about its Vision Zero goal.

Meanwhile, in the United States, 2018 proved to be the deadliest year for pedestrians and cyclists in the past three decades. According to the most recent data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 6,283 people were struck and killed while walking and 857 were killed while riding their bikes.

In the Houston area, 19 cyclists and 133 pedestrians were killed in traffic accidents in 2018. Pedestrian deaths in the region were up 75% over a decade earlier, but 2018 marked a reduction in fatalities for the second year in a row. A decrease of almost 25% from 2016 (177), and 7.6% from 2017 (144).

A total of 160 bicyclists were killed in the region between 2009 (13) and 2018, with a 46% increase in fatalities in that span. The 19 deaths in 2018 were an improvement over 2017 when 22 cyclists died. There were 534 cycling deaths on Texas roadways during the decade — 27.5% of them occurred in the Houston Metro area.

Vision Zero was an initiative created by the Swedish Parliament back in 1997 with the goal of ending all traffic fatalities: “It can never be ethically acceptable that people are killed or seriously injured while moving within the road transport system.”

The program spread to the U.S. and a number of cities have adopted Vision Zero programs — some with goals as ambitious as eliminating traffic deaths by 2024. Houston’s Vision Zero commitment calls for ending traffic-related deaths and serious injuries among all road users — motorists, cyclists, pedestrians, “other” — in the city by 2030. Last May, the Texas Department of Transportation announced a plan to zero out traffic deaths in the state by 2050.

Latest safety report shares ‘uninspiring results’

But the Vision Zero goals of many cities don’t seem to be reflected in the targets set at the state level. Since 2018, the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) has required states to set annual “safety” targets for “non-motorized deaths and serious injuries combined, which includes people walking, biking, using wheelchairs, and riding scooters and other non-motorized vehicles.”

These targets, which are tied to federal funding for safety projects and programming, are less ambitious than those of many cities, even moving backward in some states.

The 2020 Dangerous by Design report from Smart Growth America shows that 18 states set safety targets for 2018 that were higher than the number of non-motorized deaths and serious injuries that occurred in the previous year. Of those, 10 states exceeded that target. Thirty-two states set targets that reduced the number of people killed or seriously injured while walking or using a wheelchair or bike to get somewhere, and only eight succeeded.

The report’s writers called the results “uninspiring.”

33 states and DC failed their “safety” targets—more people walking, rolling, scooting, and biking were killed or seriously injured by drivers on their roads than the goals they set.

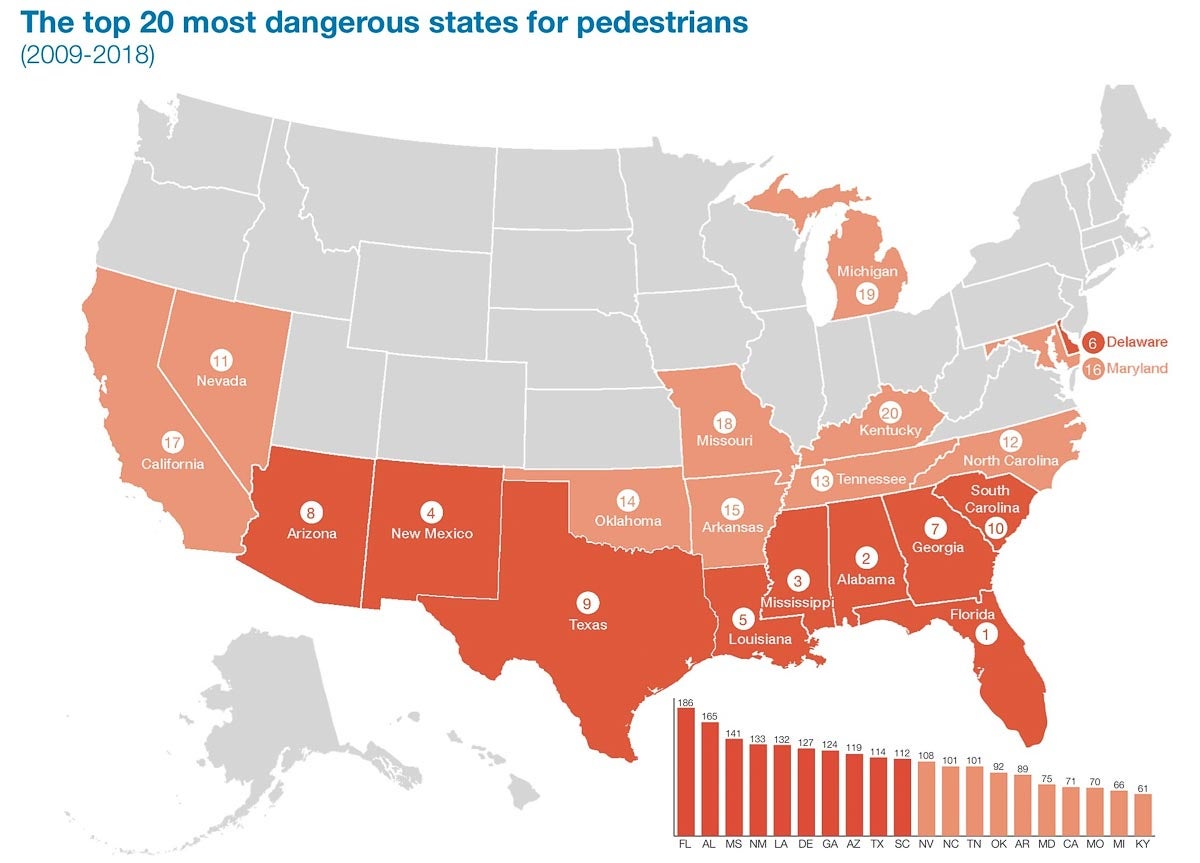

Texas was among the 24 states that set a 2018 safety target that was lower than 2017 but exceeded the target. The report ranked Texas as the ninth-most dangerous state for pedestrians. Florida and Alabama topped the list.

In 2019, the report ranked the Houston region as the 23rd most dangerous among the nation’s 100 largest metro areas.

Source: Smart Growth America

How can cities and states improve safety?

So, how did Oslo roadways become so safe? According to Bicycling magazine, the most likely reasons include: “more bike infrastructure, lower speed limits, fewer vehicles on the road overall, less traffic in residential areas, speed bumps, vehicles equipped with better technology, and better roads in general.” By the way, Oslo has a population of around 674,000.

Houston is making progress in several of these areas, including bike-lane expansion and more protected bike lanes, road improvements and measures to reduce traffic speed and volume, also known as a road diet.

In 2013, the city adopted a Complete Streets policy to make streets safe, accessible and convenient to use for pedestrians, motorists, public transit riders and cyclists. Earlier this month, the city released an update on the progress of its Complete Streets and Transportation Plan. The highlights included:

► Completion of 42 miles of high-comfort bike lanes. As a result, 1,000 additional Houstonians live less than one-half mile from a bike lane that supports all riders and abilities.

► Houston Public Works kicked off the Safer Street Initiative with safety audits at 12 intersections identified by the community as dangerous for walking and biking. These audits, and the improvements planned as a result of them, will improve the safety at those intersections for more than 3,900 people walking and biking and for people in more than 367,000 cars and trucks every day.

► B-Cycle now operates 109 stations with 700 bicycles. In 2019, B-Cycle and Change Happens! collaborated to launch the Go Pass, creating a cash-based, lower-cost alternative for residents of Third Ward. Since the launch, 22 new members have utilized the pass for 357 trips, totaling 1,467 miles traveled in and around the Third Ward-area stations.

Steps being taken to improve safety

In 2017, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner unveiled his Complete Communities program, which includes planned improvements to sidewalks and street lighting in underserved neighborhoods.

Turner added the Safer Streets initiative to the program in 2018 to improve safety for pedestrians and bicyclists. The initiative started as a pilot program in the Complete Communities neighborhoods and was later expanded to the entire city.

A 2018 report from Kinder Institute researchers showed that residents of Gulfton, one of the original Complete Communities neighborhoods, were living with big challenges stemming from street safety and infrastructure in the city's densest neighborhood.

Researchers asked respondents to identify dangerous streets and locations of near-miss incidents. Most of the reported near-miss incidents involved pedestrians and cars and often included vulnerable populations like young children, older adults and people who use wheelchairs.

Input from residents also included comments such as ...

“The car was going really fast and hit a man who was crossing the street on his bike.”

“Cars turn the corner too fast or run the stop sign and they don't stop for buses or children crossing.”

The city has worked with Bike Houston and LINK Houston to identify the 12 most dangerous intersections for pedestrians and cyclists. Safety audits were conducted on the intersections to determine improvements needed to make them safer.

Last July, the Complete Streets Act was introduced in Congress by Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) and Rep. Steve Cohen (D-TN). Under the act, federal highway funding would go to states to finance local “Complete Streets” projects.

“Our roads and sidewalks are far more than a means of transportation, they are a means of economic growth and community development, and we must make them safe and accessible for everyone,” said Senator Markey when details of the Complete Streets Act were released. “When we have ‘complete streets’, we can have complete communities – comprehensive centers for employment, education, health care, civic life, and commerce.”