For eight years running, Houston's Harris County added more people each year than any other county in the country. Though that title now belongs to Maricopa County in Arizona, Harris County and Houston are still growing. That’s a lot of new people for whom Hurricane Harvey and the unprecedented rainfall that came with it might have been their first major storm. But even for longtime and native Houstonians familiar with the area's flooding, there’s a lot they likely don’t know about flood-related risks in their hometown.

That’s the reasoning behind the latest report from Jim Blackburn, co-director of Rice University’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters (SSPEED) Center, called “Surviving Houston Flooding,” released today by the Kinder Institute in conjunction with the Baker Institute. The document, writes Blackburn, is not about fixing Houston’s flooding but surviving it by creating a “flood-literate populace.”

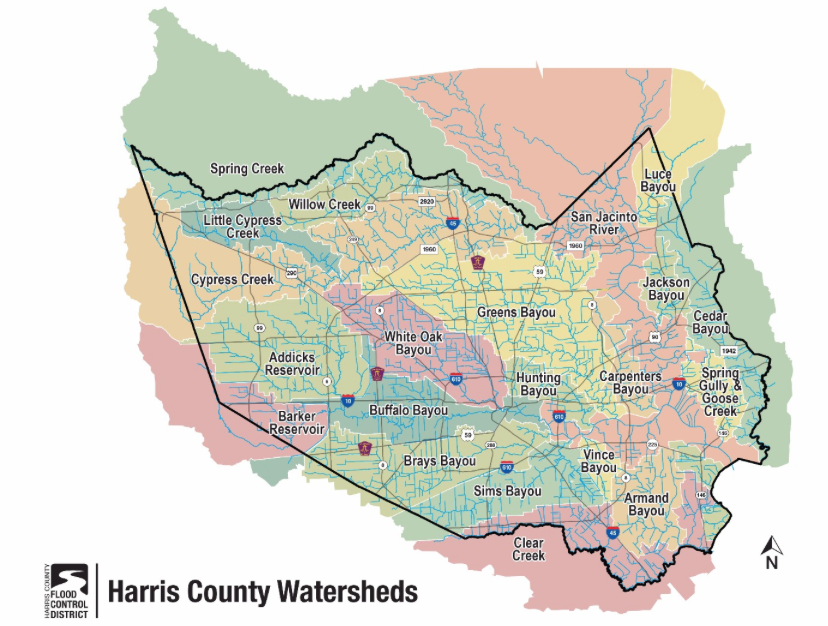

That requires a better understanding of flooding, starting with the 22 watersheds that make up Harris County, each with their own “independent flooding issues,” as the Harris County Flood Control District puts it.

“The watershed - the area within which the rainfall runoff flows to one watercourse such as a bayou, a stream, a river - is the basic building block of flood-related information,” writes Blackburn in the Houston Chronicle. “You should know yours well and understand its flooding characteristics.”

Watersheds in Harris County.

Source: Harris County Flood Control District.

By now, problems with the 100-year floodplain, used as a tool to regulate development and set expectations about the annual likelihood that a property will flood, have been widely discussed. The existing floodplain is outdated and doesn’t reflect actual rainfall frequencies, argues Blackburn. “Beware of relying on these maps,” he writes in the report. “They likely under-represent the true and current risk of flooding.” And the floodplain can be altered with what is known as a Letter of Map Revision. Meant to catch human errors, this mechanism, writes Blackburn, “can be and has been abused.”

Importantly, the floodplain doesn't include all potential sources of flooding – like street and storm sewer flooding. “A home may be flooded by water rising from the street up to and above the foundation or by flow coming down the streets from the higher portions of the watershed to the lower,” the report continues. “This type of flooding is generally not shown on maps.” Though newer regulations require certain elevations, older homes aren’t included in those.

And then there are communication gaps, also widely discussed following Harvey’s inundation. For homebuyers looking to buy a home in designated evacuation zones, for example, “no one – not the seller, not the real estate agent, not the title company, not the lawyer – is required to tell you that you are buying in an evacuation zone,” writes Blackburn.

Like the real estate industry, Blackburn argues that local government hasn’t prioritized flood prevention in its practices. “We were more concerned about building the Grand Parkway to aid and assist new development than we were about fixing Addicks and Barker dams,” writes Blackburn in the report. “That focus needs to change.”

With this in mind, surviving storms partly depends on the wisdom of people who have done it before. “Ask what roads are the first to flood during rains, which intersections they avoid, and which roads they use during flooding,” the report instructs. “Most of us that have lived here for a long time have a general idea of which routes are better during intense rains. Know your routes from home to work and school and check them out. It will pay off during a rain event. And many of us simply put off driving during severe rain events if we can.” The report also includes suggestions for people looking to rent or buy to minimize their flood risk.

Though Blackburn calls flooding “the number one threat to public health and life and economic prosperity” in Houston and Harris County, he argues that if the city makes “room for water,” it will find a way to co-exist with and survive future floods.