I began my Community Bridges fellowship during my last year at Rice, and in many ways it was the ideal ending to my undergraduate career. I often sought tangible “beyond-the-hedges” work to augment my academic experience, and the Community Bridges program aligned with that pursuit and my personal, academic, and professional goals more broadly. By pairing sociological study of urban inequality with active participation at a nonprofit community organization addressing the needs of Houstonians, the fellowship provides an opportunity to understand and engage with issues that our city’s marginalized communities face every day. As someone studying environmental science and deeply interested in its implications in cities and urban life, I aimed to partner with Air Alliance Houston (AAH) to gain the most from my Community Bridges experience.

AAH undertakes environmental research, education, and advocacy to help reduce air pollution and its public health impacts in Greater Houston. It spearheads a variety of campaigns to help achieve this, from expanding community air monitoring and disseminating pollution data to organizing action against polluters. These polluters may range from neighborhood concrete batch plants to sprawling chemical facilities along the Ship Channel. Regardless of these entities’ size, AAH pushes relentlessly for greater environmental justice by advocating for fenceline communities burdened with industrial pollution.

At the start of my collaboration with AAH, I assisted with a variety of tasks according to organizational needs and environmental happenings in the city, including monitoring emissions data during extreme weather events and preparing public comments on policy documents. My primary research project, however, centered on mapping and data analysis that explored facilities emitting the most criteria pollutants and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the Houston area. With little experience in industrial data collection—especially massive, complex, and rather unintuitively compiled datasets like those at TCEQ—I seriously doubted my ability to tackle this project. However, I was fortunate enough to be mentored in this endeavor and a variety of other data techniques by my supervisor at AAH, Corey Williams. Within a month, I picked up entirely new skills that I did not have the academic space to learn through other classes at Rice—skills I continue to use to this day.

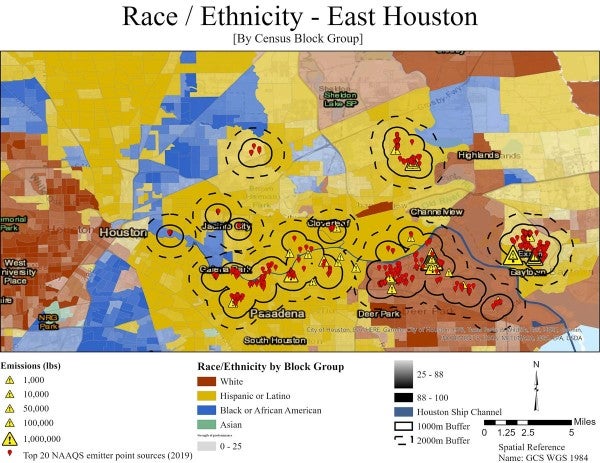

Upon plotting the location and cumulative emissions of each of these facilities, I was struck by their heavy concentration and disproportionate distribution in east Houston. At some level, I expected this general pattern because of the location of the Ship Channel. However, visualizing the extent of their proximity and agglomeration near residential areas, schools, parks and other sensitive receptors highlighted the severity of this issue.

Conducting further research into the dynamics of industrial zones in other countries, I learned that this pattern is not an inevitable byproduct of industrialization. Rather, many other nations utilize industrial separation distances to both minimize environmental risks to communities and limit residential development and expansion near toxic release facilities. In the United States, no such policy exists, and the lack of formal zoning laws in Houston exacerbates the effects of this laissez faire stance on vulnerable communities.

Utilizing datasets on demographics and health outcomes in the Houston area, I further visualized correlations between the locations of the city’s top emitters and the types of communities that shoulder their pollution the most. Whether I mapped race/ethnicity, median income, or the myriad environmental and health risks modeled by the EPA and CDC, the same underlying pattern emerged in every picture: overwhelmingly, vulnerable and marginalized Houstonians bear the brunt.

Additional regulatory data from the TCEQ also demonstrated that these facilities tend to be regular violators of their permits and face limited accountability for unauthorized releases. This project helped me learn that Houston’s globally-touted industrial and petrochemical economy has been built at a cost, often in the form of higher disease rates and quality of life issues among almost exclusively non-white and lower-income communities. From Galena Park and Manchester to Pasadena and Deer Park, the people suffering the greatest burden of these industries reap the least of its economic rewards.

Near the end of my fellowship, I was offered a full-time position with AAH upon graduation. Reflecting on all that I had learned and the skills I’d honed over the semester, I immediately accepted. Since graduating, I have expanded my efforts into additional projects and campaigns, both research and advocacy-based. I assist with community air monitoring mapping, advocating for greater pollution control to regulatory agencies, analyzing monitoring data, and compiling information on unregulated releases during natural disasters, among other things. I’ve also been able to continue and expand upon my Community Bridges project, conducting air modeling on those same polluting facilities to better understand the dispersion of pollutants in neighborhoods and receptors across the area. This work has provided numerous insights into the chemical and atmospheric elements that influence relative burdens of pollution, and, perhaps more importantly, the role this data can play in determining potential health impacts at the neighborhood level.

Working with AAH allows me to explore the nexus of data-driven research and environmental justice advocacy that drew me to the Community Bridges program in the first place. I know I want to continue working in this field and perhaps increasingly focus on reducing barriers to knowledge about air pollution issues. I am especially passionate about expanding marginalized communities’ access to the information and resources needed to challenge these issues - that have been historically and intentionally kept from them. Through its various campaigns, AAH strives to dismantle barriers to community knowledge like vague and sporadic emergency alerts during industrial accidents and inadequate public notifications during the issuance of permits to polluting facilities. In Texas, and especially in Houston, the onus of pollution awareness and vigilance is largely placed on residents instead of industry or regulatory agencies. As such, much work and research is needed to change this dynamic.

When I joined Community Bridges, I thought the program was a good opportunity to gain some professional experience while taking care of academic credit requirements. I never expected that I would be writing a blog about my full-time job with my Community Bridges partner organization almost a year later. I’m thankful for this program and the Kinder Institute more broadly for creating opportunities for students to engage deeply with the most pressing issues our city faces.

Anthony D'Souza is the Research & Policy Coordinator at Air Alliance Houston. He graduated from Rice University in 2021 with a degree in environmental science and a concentration in earth science.