Houston isn’t the first city to launch a police “task force” in response to civil unrest or police scandal — and it won’t be the last. So, what should we expect of Mayor Sylvester Turner’s new Task Force on Policing Reform?

The task force met for the first time on July 9. Local leader and activist Larry Payne chairs the task force, which will produce a report of its findings by Sept. 30. The report will have discrete reform suggestions for Houston Police Department policies about use of force, community policing, body cameras and other relevant topics. Notable local organizations, including Black Lives Matter Houston, have been critical of the task force. Others have noted task-force fatigue, and the failure of past studies from Houston commissions to yield police policy changes. (Disclosure: I will be providing research support to Kinder Institute Director William Fulton, who is a member of the task force.)

These criticisms are not without warrant: other cities’ commissions also have failed to lead to changes. So, what can we learn from these other cities?

This post will focus on another Sun Belt city’s history with police commissions during a specific era: Los Angeles in the 1990s. In 1991, LAPD officers were filmed beating Rodney King; and in 1992, the city exploded in a riot after those officers received a not guilty verdict from a predominantly white jury. In the late 1990s, there was the Rampart CRASH police corruption scandal, in which members of the city’s elite anti-gang unit seemed to be running their own criminal syndicate. That last scandal eventually led to LAPD submitting to a federal consent decree and significant reforms.

Each of these events — the assault on Rodney King, the 1992 riots and the Rampart CRASH scandal — led to different independent commissions and task forces. While Houston has not experienced unrest on the scale of 1992 Los Angeles, the Rampart CRASH scandal has some notable parallels with the ongoing controversies within HPD’s Narcotics Division, centering on officer Gerald Goines.

This brief history of LA’s 1990s commissions may help to illustrate what other major American cities’ “blue ribbon” police commissions have done, and the lessons to be learned from parallels.

Commission 1 (1991): Rodney King and the Christopher Commission

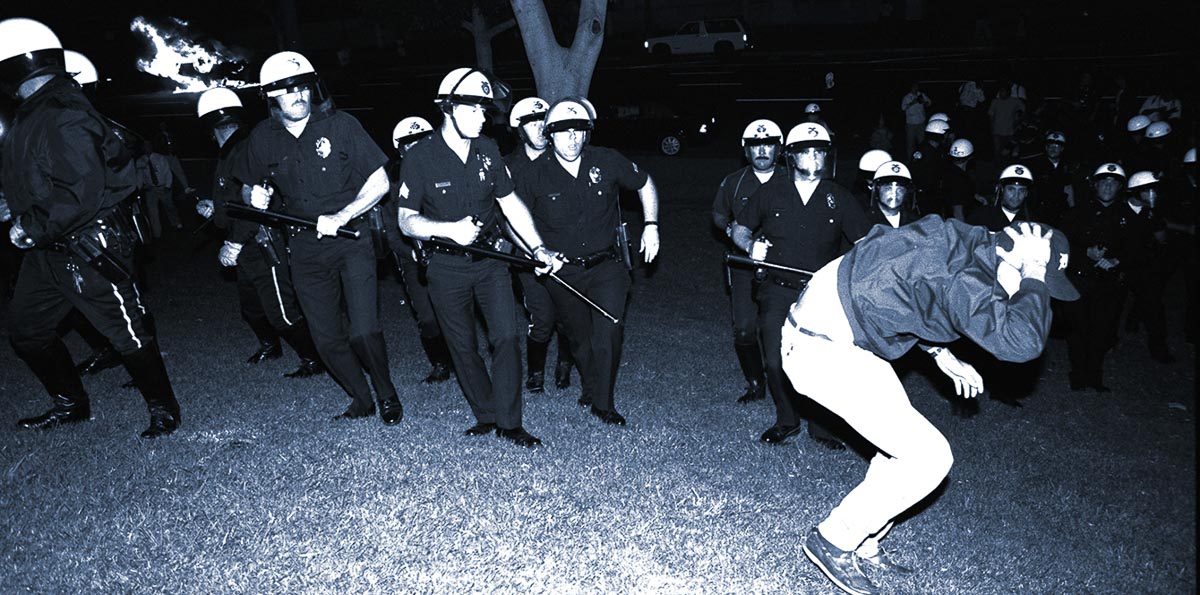

On the evening of March 3, 1991, LAPD officers pulled over Rodney King for speeding and reckless driving. The pursuit was fast enough to warrant assistance from a police helicopter and multiple officers. Many officers were present during King’s arrest, during which officers beat King while he was on the ground. Plumbing supply salesman George Holliday recorded the beating from the balcony of his apartment nearby. Initially, he wasn’t sure what to do with his video. Days after the incident, he offered his video to the LAPD, but no one followed up on his offer. He then took the video to a local television station, which aired an excerpt on the evening news and catapulted the case into a national controversy.

Less than a month after King’s assault, then-LA Mayor Tom Bradley established the “Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department” to investigate racism and use-of-force practices within the department. To lead this group he tapped Warren Christopher, who would later serve as secretary of state under President Bill Clinton (and help broker peace agreements in Israel/Palestine and Bosnia). At the time, Christopher was a prominent local citizen who was working in an LA law firm. Six other prominent citizens — mostly high-ranking academics (e.g., the president of Occidental College), lawyers and corporate leaders — served alongside Christopher. A cadre of lawyers and data analysts assisted the commission, interviewing hundreds of police officers, community leaders and criminal justice experts, and crunched quantitative police data on arrests.

Within four months, in July 1991, the commission issued its 297-page final report. It concluded that a “significant number of officers … repetitively use excessive force against the public and persistently ignore the written guidelines of the department regarding force” (p. iii). A sizable minority of LAPD officers reported racial bias among their fellow officers. The commission found transcripts of police communications in which officers called citizens “monkeys” and advocated using flamethrowers on non-white neighborhoods. The report recommended many changes to officer training, and establishing a new system of accountability and for filing complaints. It also recommended that Police Chief Daryl Gates step down from his position.

The report, which was issued on July 10, had some immediate effects. By July 13, Gates announced his intent to resign (though he did not formally leave his position until a year later, and was involved in the search for his successor). Through an analysis of complaint records, the commission identified 44 problem officers, many of whom went to counseling or quit. The city also reformed its police complaint system.

However, the commission could be considered a failure for reasons that became quickly evident.

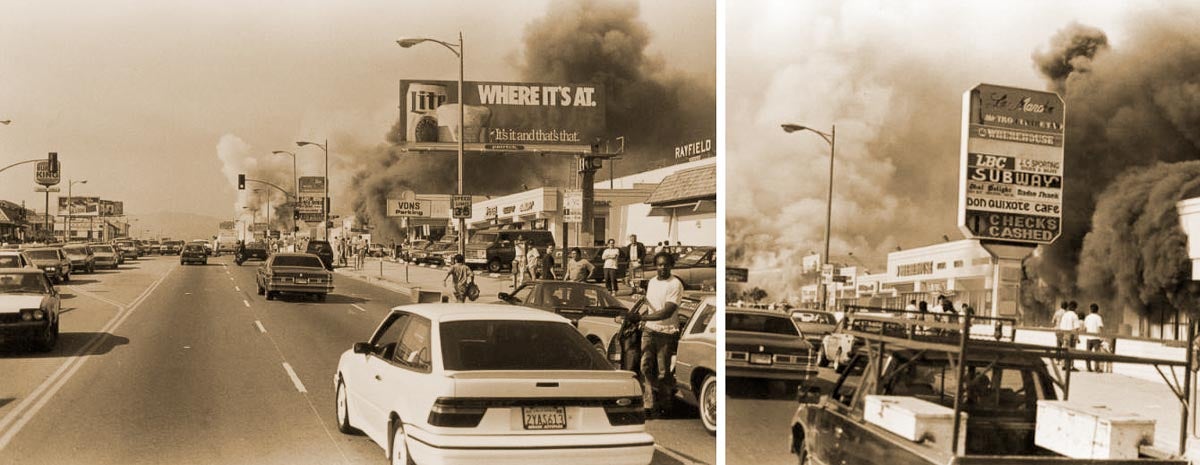

Commission 2: The Webster Commission and the 1992 Riots

An LA judge ordered the trial of the four officers who assaulted King be moved to Simi Valley, California, a predominately white exurb of Los Angeles. On April 29,1992, the predominately white Ventura County jury exonerated the four officers of all charges except for one officer’s charge (for which the jury was hung and the officer escaped a guilty verdict). The acquittals released the city’s pent-up rage and Angelenos rioted. Less than one year after the Christopher Commission delivered its report, racial injustice in the city’s criminal justice commission again exploded into the national news. If the goal of the Christopher Commission was to create a more just police force, the residents of Los Angeles did not seem to think it succeeded.

After three days of rioting, Mayor Tom Bradley again formed a commission, choosing William Webster to lead it. Like Christopher, Webster had significant federal government connections — he had recently retired as head of the CIA, and led the FBI before that, and also served as a federal appellate judge. (Unlike Christopher, Webster did not have roots in Los Angeles.) The Webster Commission began in October and finished in May, and its 400-plus-page final report was similar in scope, methodology and structure to that of the Christopher Commission.

Its findings seemingly were less critical of the LAPD than those of the Christopher Commission. It largely did not blame the LAPD for the riots or their escalation. Rather than bluntly arguing that the LAPD had a culture of excessive force (as was the case with the Christopher Commission), it found that the department overemphasized special units and de-emphasized patrol work. Its suggestions were more technocratic — the need to improve communication between police and political leaders, and restructuring the department’s workflow — than advocating for structural changes to how the city was governed or made social investments, which were among the McCone Commission’s recommendations in 1965, following the Watts riots.

Commission(s) 3+: Rampart CRASH and the consent decree

The beating of Rodney King and the 1992 riots have a secure spot in the national consciousness (I actually remember learning who Reginald Denny was by watching this “In Living Color” sketch). However, a major police scandal five years later arguably had a larger effect on changing the LAPD’s daily operations.

The details of the Rampart CRASH scandal warrant retelling, both because they aren’t well-known outside of Los Angeles and because they are, to put it bluntly, rather lurid. (This excellent long-read from The New Yorker in 2001 covers the story). In March of 1997, five years after the riots, a white police officer named Frank Lyga was returning from an undercover sting operation when he fatally shot a Black man during a road-rage incident. The dead man was Kevin Gaines, another LAPD officer who was not in uniform at the time, and was part of an elite anti-gang unit called CRASH, which stood for Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums, in the city’s Rampart division (named after Rampart Street, where the division is located).

A white police officer fatally shooting a Black officer is a scandal in itself: Gaines’ family retained Johnny Cochran, and ended up settling a wrongful death suit. However, further post-mortem investigations raised more questions. Gaines seemed to live far beyond a patrolman salary’s means, and also served as a bodyguard for former Death Row Records CEO Suge Knight. His personal file contained bizarre incidents, such as a fraudulent 911 call in which he assaulted the responding officers.

Gaines was close to Rampart CRASH officer David Mack, a former University of Oregon track star. Mack also had connections to Knight and seemed to live a lifestyle beyond a public servant’s means. After Gaines’ death, LAPD investigators pinned a November 1997 bank robbery on Mack. Shortly after the robbery, Mack traveled to Las Vegas with other Rampart CRASH officers.

One of these officers, Rafael Perez, became the officer who blew open the CRASH scandal. In August of 1998, the task force arrested Officer Perez, naming him the suspect in the theft of multiple pounds of cocaine from the Rampart evidence room (and replacing the cocaine with Bisquick). Unlike Mack (who did not cooperate with police questioning), Perez talked to investigators extensively over 50 sessions. He admitted to lying about a non-fatal shooting of an innocent person during a blown narcotics operation, and planting a gun on the shooting victim. He insisted that this was common Rampart CRASH practice, and that they all kept guns and drugs in case they needed to plant them. He implicated many other officers in beatings, theft and the planting of evidence.

Perez’s testimony remains controversial. As a corrupt officer (by his own admission), he was a textbook unreliable narrator. Many of his most salacious charges could not be corroborated and he did not name his closest associates (Gaines and Mack) in serious wrongdoings. More than a dozen officers lost their jobs. Many gang and drug convictions ended up being overturned as a result of Perez’s testimony, and the LAPD paid more than $125 million in civil suits that stemmed from the scandal.

In summary, one of LAPD’s anti-gang units appeared to resemble a criminal gang. The scandal torpedoed the LAPD’s already lackluster public legitimacy. In fact, the scandal was serious enough to beget another commission — or rather, commissions.

In 1999, LAPD chief Parks formed a Board of Inquiry to investigate the internal culture of CRASH units and their activities. Unlike the Webster and Christopher commissions, which included outsiders, the Board was composed entirely of LAPD staff and officers. In March of 2000, it issued a 355-page report containing mostly local-level suggestions for reform (though it advocated change to some state-level laws that would allow more-thorough investigations into officers’ criminal and psychological records). Soon thereafter, the LAPD dissolved CRASH units citywide and replaced them with another anti-gang unit.

There also was the Rampart Independent Review Panel, composed mostly of influential community members. This review panel was initiated by the LA Police Commission — the civilian board that formally governs the police department — because of the lack of community input in the Board of Inquiry report. Its 258-page final report can be found here.

Then, there’s the “Chemerinsky Report,” also known as “An Independent Analysis of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Board of Inquiry Report on the Rampart scandal,” which was written at the request of the Police Protective League (the police union) and highly critical of the Board of Inquiry’s earlier report. There’s also the “Collins Report,” written in 2003 by the Los Angeles County Bar Association. Each report seemed to resemble an opportunity for a new constituency — the police, the police union, diverse citizen groups and lawyers — to put their interpretation on the event.

The Rampart CRASH scandal led to one very important outcome that neither the King beating or the 1992 riots could make happen: a federal consent decree. Since 1996, the federal Department of Justice had been investigating the LAPD for racism and civil rights abuses. In 2000, the Los Angeles City Council overwhelmingly voted to accept a consent decree, despite objections by the mayor and the LAPD police chief. The decree placed federal oversight on the LAPD until 2013, when it was finally lifted. During that period, the LAPD escaped major nationwide scandals and underwent significant structural changes (such as implementing COMPSTAT managerial practices). During the consent decree period, public satisfaction of the department significantly increased and serious crime decreased (though this was a common trend in many major cities during the decade).

Conclusion: bringing it back to Houston’s task force

This report on the Rampart scandal, written by a unique collaboration with police, police union leaders, civil rights activists and others after the consent decree’s beginning, contains both a very good post-mortem of the Rampart scandal and good summaries of the task forces covered above. It blames the scandal on political pressure on the police, a lack of political accountability and an endemic culture of abuse. The report was written long enough after the scandal to include broader reflections on the scandal’s fallout. It also contained guidance for the Department of Justice, which had the power to mandate changes to the LAPD because of the ongoing consent decree.

The earlier commissions — Christopher, Webster, the Board of Inquiry — focused mostly on local-level changes to LAPD practices. However, as mentioned in a prior blog post, efforts to reform or overhaul policing should not forget the influence of the federal and state governments. The state of California and the federal government are largely absent from these commissions’ reports. It should be noted that it was during the post-Rampart federal consent decree that the police department actually underwent significant changes and their public perception improved.

Despite being more infamous events, the 1992 riots and the Rodney King beating arguably did less to change the department than the consent decree — a tool that has proven effective in reducing police violence elsewhere. Furthermore, legal scholars argue that state-level prosecution of excessive force by the police can help curb police misconduct and violence.

Current and future task forces, while often formed by municipal governments, should perhaps consider partnering with state governments in order to enact changes. States wield the police power with the U.S., and our police officers are a human manifestation of that power. Thus, the mayor’s task force should not forget the importance of Austin in guiding Houston’s police.

No one hopes that the Goines case snowballs into HPD’s own Rampart CRASH scandal; however, one does hope that the commission assures it won’t happen in the future.

Unlike the post-riot Webster commission or the post-Rampart Board of Inquiry in LA, Mayor Turner’s task force is led by an established non-police community leader. Also unlike most of the LA commissions, this task force features a very large array of local interests. However, similar to those LA commissions, Mayor Turner’s task force has little input from the state or federal government. It must produce a report in a short timeframe. Ideally, the diversity in expertise, knowledge and backgrounds of the current task force members can guide the commission’s research and writing, and help produce a report that yields substantive results. Otherwise, like LA in the 1990s, Houston may have more commissions in the future.