In blue scrubs with her arms folded, a nursing assistant smiles into the camera.

"I save lives," reads the text beside her, "Can I be your neighbor?"

The image is one of several created by Houston's Housing and Community Development Department being circulated online and in the mail to some residents with their water bill to promote fair housing and push back against resistance to affordable housing development across the city. The campaign was launched in April for Fair Housing Month but the department says it plans to extend efforts throughout the year, hoping to shift the citywide housing conversation.

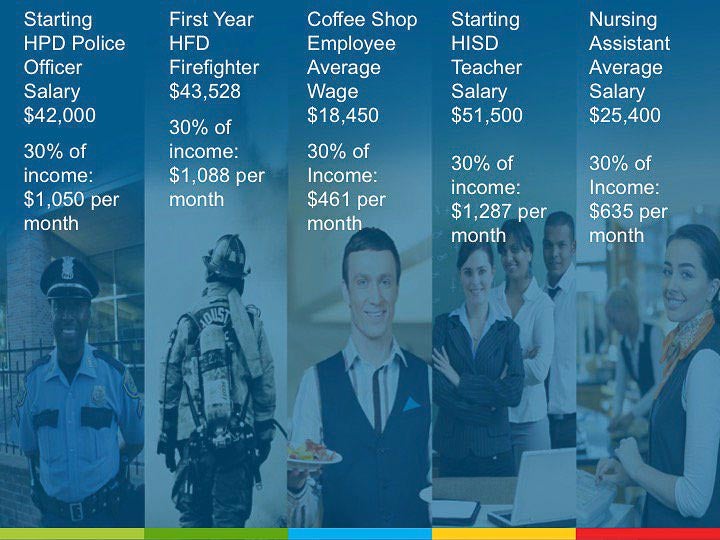

Teachers, medical workers and firefighters are all included as examples of the types of people who likely cannot afford rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the city, given their annual salaries. But even within that group, there's fair spread in terms of what's affordable. A nursing assistant, for example, has an average annual salary of $25,400, meaning if she spent a third of her income on rent, she could afford a monthly rent of $645. Then median rent for a two-bedroom unit in Houston is around $910, according to the housing department.

But even that varies by neighborhood. So in the Upper Kirby area, for example, the fair market rent, calculated by the federal housing department, for a one-bedroom apartment is $1,190. And fair market rents are defined as those in the 40th percentile, meaning 60 percent of the rental units in that area are going to be more expensive.

In other words, the images proclaim: "They cannot live where they help people."

The effort, meant to highlight Houston's growing affordability problem as home prices grow at five times the rate of income, according to the department, intersects with a national movement meant to turn the tide against "not in my backyard," or NIMBY, politics.

The alternative -- so-called Yes In My Backyard efforts, or YIMBY -- have focused on affordable housing, transit and pro-density policies across the country. The national YIMBYtown conference met in 2016 in Boulder, Colorado marking the first national gathering for the movement. This year's meeting will be in Oakland, California.

The issue has particular resonance in Houston.

"Three issues prompted the campaign," said Tom McCasland, director of the housing department in Houston, in an email. "Rising home and rental prices, misconceptions about who benefits from affordable homes, and the need to communicate with and hear back from the silent majority of residents who would say 'yes' to quality affordable homes in their neighborhood."

Resistance to affordable housing has received heightened attention after a federal housing investigation found the city allowed racially-motivated local opposition to motivate its decision to shelf a low-income housing tax credit project that would have been the first built in a so-called "high opportunity area."

Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner has pushed back against those findings and moved ahead with his Complete Communities initiative, a still-fuzzy effort that promises to revitalize five historically under-served neighborhoods in the city.

At the same time, the city is completing its housing plan and the housing department also has plans to help 350 families with young children who receive housing vouchers move to low-poverty neighborhoods with good schools. Because of the voucher freezes for both the county and city housing authorities, that program will have to work with existing voucher holders who want to move, rather than new ones.

Because landlords are allowed to discriminate against voucher holders in Texas, these neighborhoods are often effectively off limits to voucher holders. There's also talk of a citywide land trust but more immediately the housing department is streamlining its Homebuyer Assistance Program and working on an educational initiative to get more qualified homeowners to sign up for the homestead exemption.

Since 2015, the housing department has done some sort of annual campaign for Fair Housing Month, but this year, the campaign also comes with educational presentations meant to convey the need for affordable housing and help shift the conversation.

"It is our goal to change the conversation with the general public about affordable homes by having these discussions during an educational presentation in a Super Neighborhood or civic association meeting rather than in a heated public hearing," said McCasland. The campaign received some guidance from an advisory committee, which included staff from the Kinder Institute for Urban Research.

"We hope this campaign will put a human face on the need for affordable homes and educating the viewer that when affordable homes are opposed, it denies others who provide valuable services to our city the opportunity to improve their quality of life," said McCasland.

Local opposition can play a deciding role in whether subsidized housing developments, like those financed with low-income housing tax credits, get the green light from the city and state.

"We also wanted to inspire viewers to become advocates for the development of affordable homes by announcing their support in public meetings where affordable home proposals are discussed, submitting letters of support for affordable home proposals, or joining an organization that supports affordable homes and/or fair housing rights."