“The thing about garage apartments or ADUs is, they’re kind of hidden. It’s in the backyard, behind the main house,” said Adam Berman, a Rice architecture student who, along with colleague Siobhan Finlay, won a citywide competition for ADU design. “For us, the idea was to make something you could see from the street, that would blend well with the character of the neighborhood, but not be too conventional.”

The design, dubbed “Double House,” envisions a 530 square-foot dwelling made of two offset structures that create front and back porches, contrasting exterior materials of brick and corrugated metal, and is wheelchair accessible.

The design now goes into further development as part of Rice’s Construct program, which is already building another student-designed ADU in Houston’s First Ward. After “Double House” is fully vetted, the city will host it as an “almost build-ready” plan. (Site-specific permits and details would have to be worked out case-by-case.)

“It’s exciting to see more dialogue about ADUs, and it would be incredible to see our design actually built some day,” said Berman, who lives in a garage apartment near the Rice campus.

Lynn Henson, division manager for the city’s planning department, has become the city’s leading ADU advocate. She secured an AARP Challenge Grant last year to fund a program to increase awareness and engagement with ADUs—including organizing the design competition.

“The code of ordinances allows for the construction of ADUs, but I don’t know how many people really think about adding an ADU to their property or including it in their design before construction,” she said. “So there is great potential, but there are so many factors that come into play in the decision to build one—cost being a main factor—and just knowing what’s involved.”

A little push could go a long way. From 2016 to 2019, California’s legislature compelled cities to relax regulations and reduce barriers to ADU construction, including rules on minimum lot sizes, setbacks, and parking. As a result, statewide ADU permits more than doubled, from 6,000 annually in 2018 to more than 15,000 in 2019, according to the Center for Community Innovation at UC Berkeley. Much of this increase was concentrated in the Los Angeles metro area, which permitted over 11,000 new units from 2017 to 2019.

The Accessory Dwellings blog suggests that if LA keeps this pace up, one out of every 10 single-family homes will have an ADU by 2026—offering tens of thousands of additional units of housing in a city that desperately needs it.

Could Houston experience a similar boom? It seems possible, especially if some key policy tweaks being discussed by the city’s Livable Places Committee move forward. In particular, the group has discussed relaxing parking requirements for properties located near transit corridors. There is also a discussion about allowing a single-family lot to contain up to four housing units, allowing for multiple ADUs or duplexes (or a combination of these) on a lot.

Where are the ADUs?

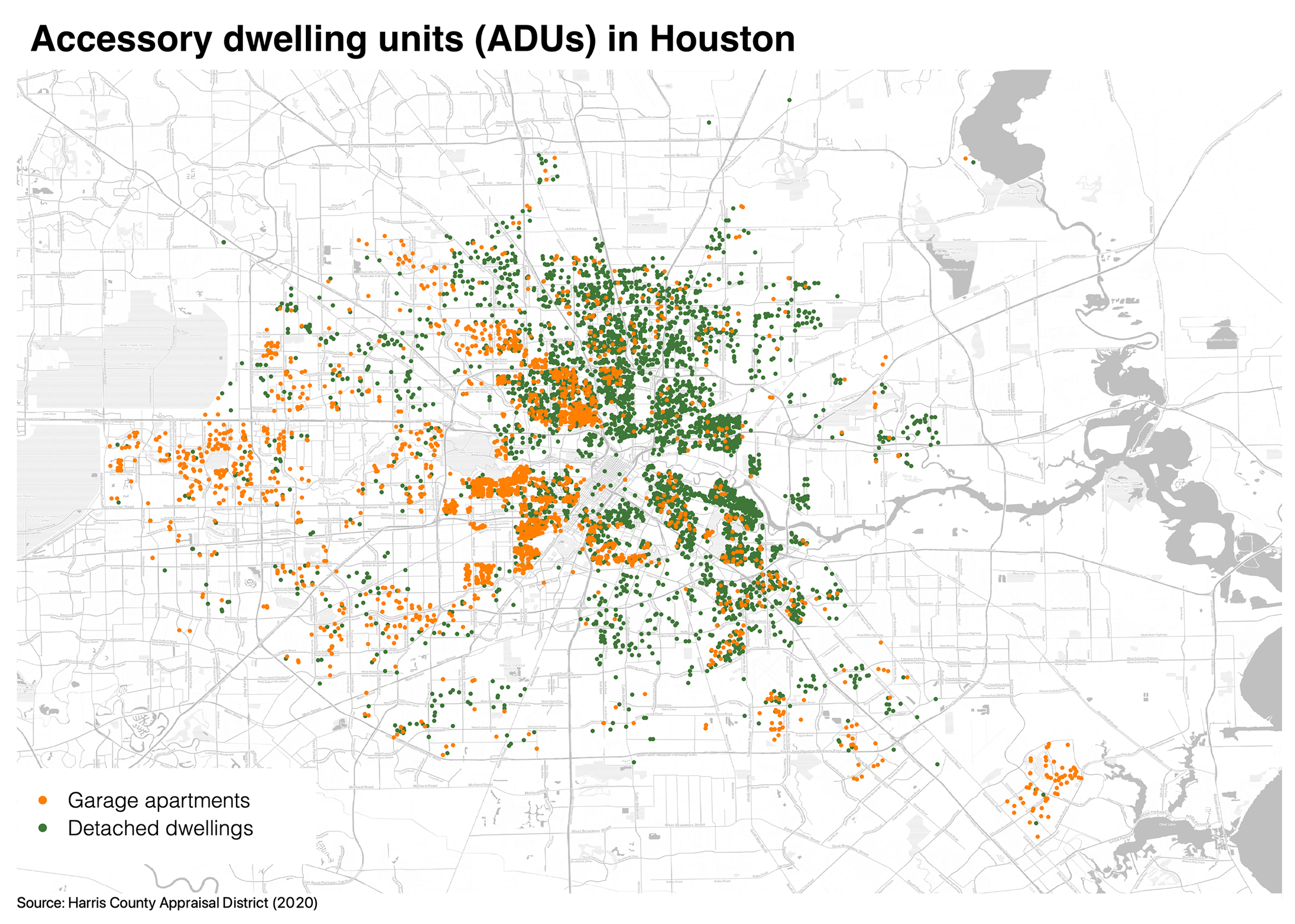

The city already has thousands of units of accessory housing, but there is potential for much more. According to the city’s estimates, Houston is home to around 3,600 garage apartments, but that’s just one kind of ADU. There are other detached buildings that could fall under this definition.

With the help of our Urban Data Platform team and the recently released 2020 Harris County Appraisal District dataset, we identified 5,300 potential detached residential dwellings located alongside single-family homes in Houston.

This number carries some caveats. We defined an ADU as being a secondary residential building associated with a single-family home in Houston city limits with at least one room defined by HCAD as a bedroom. We also limited our search to include secondary dwellings of 900 square feet or smaller.

Technically, to be a permitted ADU in Houston, these units also have to have a kitchen and bathroom, but we did not account for that in our initial search. So some units may not technically be a permitted ADU because they lack a kitchen, for example, but they all nonetheless could operate as de facto housing units, while a portion could be offices, studios, game rooms, etc. (It’s common for new builds to skip including a full kitchen in order to avoid triggering additional building requirements.)

We also attempted to replicate the city’s number for garage apartments but could identify only 3,000—a few hundred short—but the resulting list looks close to the city’s estimate, with concentrations on west side of the Inner Loop.

Of the 5,300 properties we found, about half fell in just three neighborhoods: East End, Kashmere Gardens and Northside. (Garage apartments, meanwhile, are more concentrated in the Heights, River Oaks and University area neighborhoods.) This suggests that ADU-style buildings could already be providing a form of affordable housing in the city’s working class neighborhoods as well as in amenity-rich Inner Loop areas.

But the data also shows swaths of Houston with very few units. In particular, the outer-ring, inside-the-beltway suburbs of Spring Branch, Oak Forest, Garden Oaks, Sharpstown, Meyerland and Westbury have relatively few secondary dwellings. Sharpstown, for example, has around 8,000 single-family homes but only 21 garage apartments and 19 detached dwellings, according to the data we found.

ADUs are allowed anywhere in the city except where they might be limited by deed restrictions. Some neighborhoods may not allow them at all or may not allow them to be rented out, for example.

Backyards at the forefront

They are not a housing silver bullet but ADUs are well worth a fair hearing from a policy perspective. Houston may already be relatively less restrictive in terms of regulation, but encouraging more construction may take more than a great public relations campaign. One key will be making financing more accessible in targeted areas, Henson said.

“One of the really compelling things I see is the ability for less privileged households of color to build wealth, but these same households have the highest barriers to financing,” Henson points out. “That’s an area where we need to have conversations with the housing department and include local financial institutions in that conversation.”

Homeowners in affluent neighborhoods like Montrose or the Heights area rarely face financing barriers because they already have significant resources, and an add-on apartment is often seen as an investment that pays for itself—either through tenants, short-term rental stays or added value to the home itself.

In the case of California, only 8 percent of new ADU owners in California intended to list them on platforms like Airbnb. About half of the owners rented out the units to long-term tenants, with most of the remaining owners either using the space for additional family members or some other personal use.

Given the dire need for affordable housing in Harris County and Houston, ADUs are attractive simply from a cost-per-unit perspective.

In California, the median construction cost of newly permitted ADUs was $150,000, according to a study by the CCI and the Terner Center at Berkeley; city officials in Houston think that would be a reasonable estimate here as well.

That is high enough to put it out of reach of all but the most affluent homeowners, but it’s a steal compared to the $480,000 median per-unit cost for multifamily projects in California financed by the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, according to the Terner Center.

Those costs aren’t a California phenomenon: A recently approved project in Houston’s Midtown will cost over $335,000 per unit to build, about half of which will be subsidized by the city’s multifamily recovery fund. (Even if the millions in subsidies were only divided among the 80 units that will be made affordable to low- and moderate-income tenants, the per-unit cost is around $245,000.)

There’s an argument to be made that some public dollars could help incentivize ADU construction, especially as construction costs are increasing across the board. It would make sense to concentrate these efforts near job centers and transit access corridors.

La Mas, a non-profit organization based in LA (with a former Houstonian as one of its co-founders), is piloting something like this. The community advocacy group is providing five homeowners in targeted neighborhoods with financing, design, and construction support, as well as landlord training, if they agree to house a Section 8 eligible tenant in an ADU for at least five years. These efforts coincide with a citywide push for more ADU construction that made 20 ADU floorplans available to the public.

In Atlanta, Kronberg Urbanists + Architects has worked with the city government there to open up more ADU construction in the zoning code. It also established ATL ADU Co. to offer design-build services with a one-stop-shop approach. But to really clear the way, the firm suggests allowing fee-simple ADUs that can be financed and owned as standalone housing units with separate owners, which could lead to better appraisal and financing practices. That approach could have compelling results as well.

Clearly, these units are not ideal for every homeowner and neighborhood, but as Harris County anticipates needing at least 20,000 more units of affordable housing, Houston’s backyards could play a big role in offering more choices.