At 4 a.m. on a Thursday last July — in the midst of nationwide turmoil about the heroes we create when we put statues in public parks — a large bronze statue of Father Junipero Serra was removed from a highly visible location in front of Ventura’s classic Beaux-Arts City Hall. But it wasn’t toppled by protesters.

Yes, there had been a lot of protests — not only from the descendants of native Chumash whom Serra enslaved but also from Father Serra’s defenders, who created their own group called Defend Serra. But in the end, it wasn’t the protesters who roped the statue and took it down. It was removed by order of the Ventura City Council, which made the decision after a lengthy and intense process that involved two emotional public meetings and a decision by the Historic Preservation Committee that the Serra statue wasn’t a historic landmark after all. The statue was not defaced or destroyed but rather moved to nearby Mission San Buenaventura — the last mission founded by Father Serra and, ironically, an institution elevated by Pope Francis to the status of basilica in the middle of the controversy.

For some, the removal was the beginning of a healing process that would allow the community to confront its colonial, racist past. For others, it was a sad turn of events, eliminating an iconic statue that had been the very symbol of Ventura for more than 80 years. (The best accounting of these conflicts came in a blog from Ventura native Michael Oberg, a professor at SUNY Geneseo who specializes in Native American issues.)

But for me, it was a classic Ventura moment: Talk City had triumphed again.

In my book "Talk City," an account of my years on the Ventura City Council, I describe how Ventura was the kind of town that could only take action after talking things through — sometimes at seemingly endless length. This could be frustrating, but also rewarding — because once we talked things through, the decisions tended to stick. Nobody was muscling anybody else into making a decision. For whatever reason, this approach is built into the city’s political DNA.

In most ways, Ventura is a typical Southern California beach town. It’s a pretty and historic working-class oil town 60 miles northwest of Los Angeles, a regionally important surf spot, one of California’s original Mission towns, seat of the Ventura County government, gradually becoming a suburb of uber-expensive Santa Barbara and, to a lesser extent, uber-huge L.A. My family moved there in the ’80s because it seemed like a good place for our kids to grow up, and it was. Even today, Ventura has an unusually robust community life, where people know each other many different ways — through PTOs, soccer leagues, senior centers, community orchestras, art programs, environmental organizations, and all kinds of other activities.

Yet from the beginning I could see that Ventura had a lively, colorful and sharp-elbowed political scene. The police and fire unions, the Chamber of Commerce, the developers, the local anti-growth environmentalists — all were in constant battle with one another. The “Letters To The Editor” page of the local newspaper was immensely entertaining reading. The gadflies were far more interesting in Ventura than anywhere else I could recall. Outbursts had become so disruptive at City Council meetings that applause had been banned and replaced with the American Sign Language version of applause instead — a kind of wiggly hand-waving above the head that made it seem as though the City Council Chambers had just been infected by baseball’s “Wave”. In some ways, it was typical small-town politics; in other ways, it was as high-pressure and ruthless as a presidential campaign.

Sometimes we couldn’t even agree on what to call our city. The official name is “San Buenaventura,” named for our mission, which was in turn named for St. Bonaventure, the 13th Century Franciscan saint — so named by Father Serra, who was also a Franciscan. (I am the only former mayor of San Buenaventura who’s a graduate of St. Bonaventure University!) Some wayfinding signs say Ventura; others say San Buenaventura. One night, a fellow councilmember said: “The signs should say San Buenaventura — that way everybody will know they’re in Ventura.”

Although Ventura often seemed paralyzed by the political diversity of the residents, I grew to love practically everybody who was involved in politics or civic life. Rarely did they fit into a neat political box. Surfing environmentalists were often hard-core libertarians as well. The evangelical pastors, though extremely conservative on most political issues, had a strong sense of social justice and were committed to helping the homeless, single mothers with small children, and others who were having a hard time. Like most coastal California town were ballot measures are the norm, if you’re an elected official the voters are all over you, everywhere, all the time.

And you never knew where help would come from next. One Sunday after a service at the local Unitarian Universalist Church, I was approached by a man in his 30s wearing all black with several tattoos. He was accompanied by his wife and daughter, both of whom were dressed in all black with heavy dark makeup.

“Mayor Fulton,” he said, “I just wanted to say we love what you’re doing. We are so excited about where Ventura is going.”

I thanked him in a perfunctory way, and he added:

“We were wondering — how can the Goth community get more involved?”

It was this combination of passion, political diversity, and quirky sense of commitment that made Ventura a wonderful place to live — and often a frustrating place to be an elected official.

Frustrating because there were so many competing points of view and it often took a long time to work through them all. It could be hard to move past the desire to talk about everything forever in preference to actually doing things. As we used to say at the City Council meetings, “Everything has been said, but not everybody has had the chance to say it.” I had no problem with endless talk if it led to a consensus to act. Often I was frustrated, however, when the talk seemed to be an end in itself and served as a process designed to reach a consensus to do nothing. Because doing nothing was a choice about how to proceed — and not always a good one. This was often the default decision, for example, about new housing projects — a decision that often helped to retain our small-town atmosphere but drove our own children out of town because of high housing costs. (The median home price is over $600,000 and Ventura has one of the tightest rental markets in the country.)

Yet the endless talk often resulted in a conclusion everybody could live with — and one that had true consensus, even if outside political forces accustomed to hardball politics didn’t quite get how we did things. When I ran for re-election in 2007, for example, one of the major issues was the question of whether to permit Walmart to take over a former Kmart store. Walmart wanted a 200,000-square-foot store that sold groceries. Many local residents sincerely didn’t want a Walmart. And the United Food and Commercial Workers, which represented workers at major grocery chains, wanted the City Council to adopt an ordinance essentially prohibiting large retail stores from selling groceries — a common tactic the union had used throughout California.

The union pressured me to introduce such an ordinance during the campaign, but I declined, in part because I knew the ordinance wouldn’t pass. I encouraged the union to let the “Talk City” approach run its course and in all likelihood the union’s desired outcome would come about. In contrast to my first election, the local labor council didn’t endorse me, though I won re-election anyway. Two years later, with the Walmart issue still raging, the union placed the ordinance on the ballot — but it lost. Eventually, after a lot of typical Ventura talking, we placed development restrictions on retail in the vicinity of the abandoned Kmart store. Walmart remodeled the store and moved in — but without groceries. Those who didn’t want Walmart in town at all were disappointed, but we had accomplished the goal the union said it wanted all along: No groceries at Walmart. We just did it the Ventura way.

As we have with so many other issues over the years, especially issues where our history conflicts with our current values. Around the time I was elected to the City Council, there was a raging debate about whether the cross in the park above City Hall was a historic landmark that should be retained or a religious icon that should be removed. After much discussion, the city sold the land under the cross to a nonprofit conservancy so that it was no longer officially part of the city park. A few years later, some local activists wanted the city to restore the city’s original cemetery — which had, shamefully, been converted in the 1960s to a park with no headstones — to its original condition. Again after much discussion, the city found ways to retain the park-like setting while making the cemetery a more prominent part of the landscape. And so on.

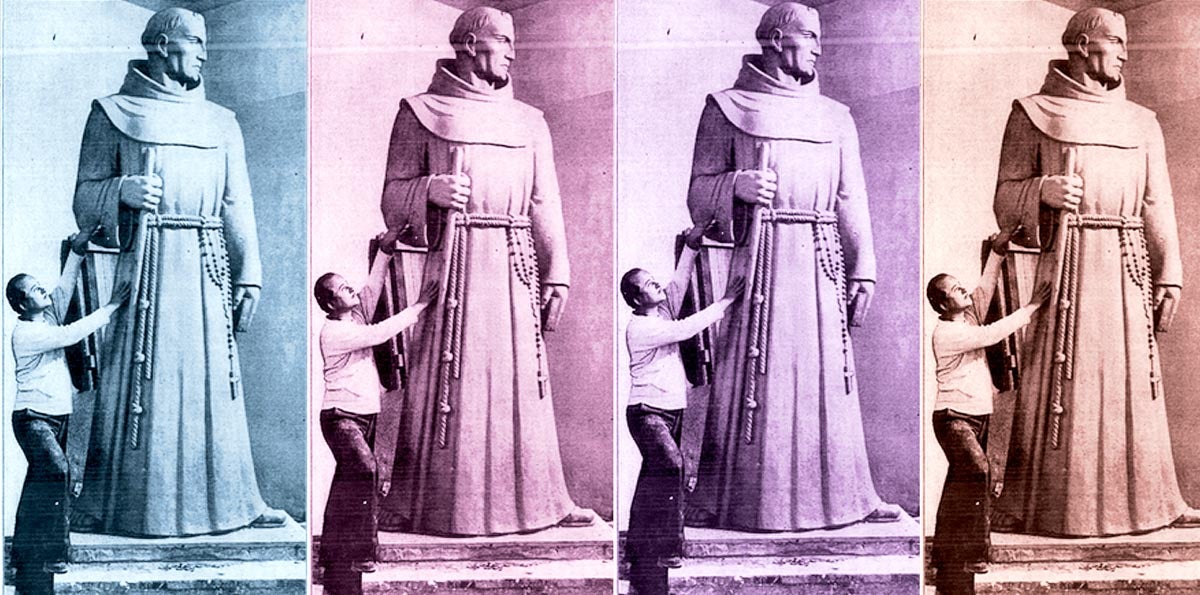

Though it has been many years since I served on the Ventura City Council, I saw a similar pattern in the debate over Father Serra’s statue. The original statue was a Depression-era Works Progress Administration project designed by prominent sculptor Uno John Palo Kangas. High on a hill in front of City Hall, looking down California Street to the ocean, it was designated as Ventura’s historic landmark №3 in 1974. After more than 50 years of exposure to Ventura’s salt air, the concrete status was replaced by a bronze replica in 1989. Whatever one things of Father Serra’s reputation, it was hard to imagine Ventura without the statue.

Father Serra was canonized by the Catholic Church in 2015. But for many years the Chumash tribal leaders in the Ventura area lobbied for the statue’s removal. On a Saturday in June, protests at the site of the statue nearly led to a classic “toppling”. But the protesters didn’t take the statue down, and then a remarkable, Ventura-like thing happened: Three community leaders proposed moving the statue. Who were the three? The mayor of Ventura, the Chumash tribal leader, and the pastor of Mission San Buenaventura.

Thus began a month-long debate about what to do with the statue — a debate that saw more protests but no toppling. The local historic preservation committee found that despite being Historic Landmark №3, the statue wasn’t really historic because the bronze replacement wasn’t the concrete original. The City Council then conducted two long meetings with dozens of speakers on each side before deciding to take the statue down and turn it over to the Mission, which put it in storage while figuring out what to do with it. The statue was removed without incident early in the morning in late July. (You can watch a video of the statue being removed here.)

Not everybody is happy with the ultimate outcome. You could argue that the decision to revers the historic landmark designation was a bit tortured. A group called the “Coalition for Historical Integrity” has sued to reverse the decision. And, of course, a bigger question looms: If you remove Father Serra’s statue because of a shameful history, what do you do with the identity — indeed, the very name — of the city itself, which flows from the very mission that Father Serra founded.

The fact of the matter is that you can’t make everybody happy in a situation like this. But you can minimize the points of disagreement and find peaceful alternatives to a confrontation by talking things through, as Ventura has always done.

A lot has changed about Ventura politics in the years since I left office. Among other things, the city shifted from at-large council elections in the odd year to district elections in the even year — changes that have led to a much more demographically diverse City Council. But the essence of the place has not changed. It’s still a place people identify with intensely — a place people want to protect, even if it means talking endless about what to do. And though that quality makes political debate difficult at times, it also creates a remarkable strength and resiliency that has always helped Ventura thrive. After watching the Father Serra debate, I love Talk City as much as ever.

This essay originally was published on Medium.