Image via Kinder Institute.

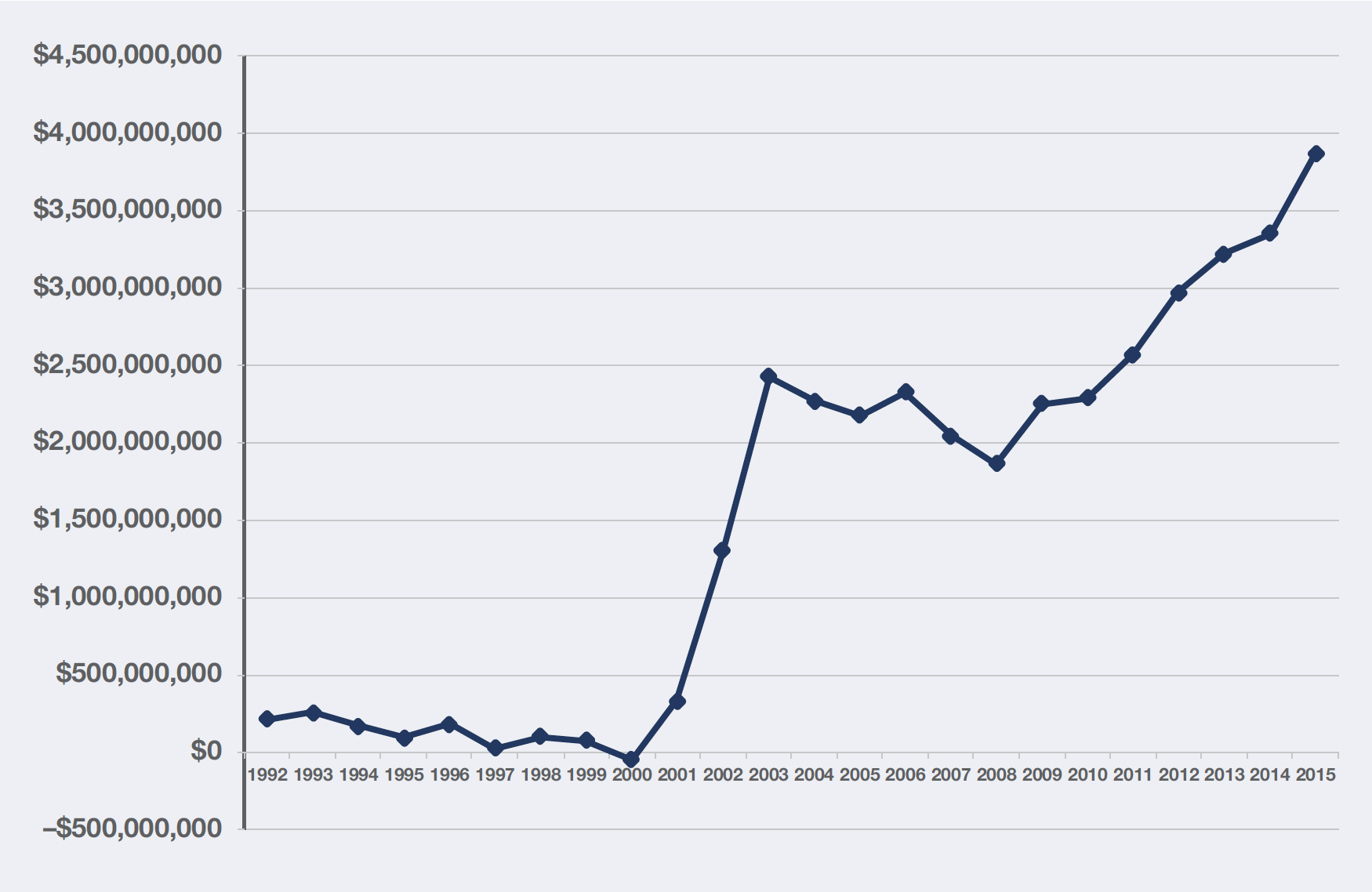

The chart above shows, in stark terms, the monumental challenge facing the city of Houston. Today, the city’s unfunded pension liability -- the value of promises it’s made to employees that it hasn’t set aside resources for -- is nearly $4 billion.

It’s a huge sum -- but what's even more staggering is just how quickly it accumulated. In 2000, it was $0 (or, technically, slightly less, since its pension assets exceeded its liabilities).

The latest report from the Kinder Institute, “The Houston Pension Question,” addresses a fundamental question: how did this happen? Perhaps more importantly, it explores the steps that city leaders, city employees and city taxpayers can take if they want to reverse the trend. The report is supported by a detailed analysis of each of the city’s three pension plans, performed for the Kinder Institute by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

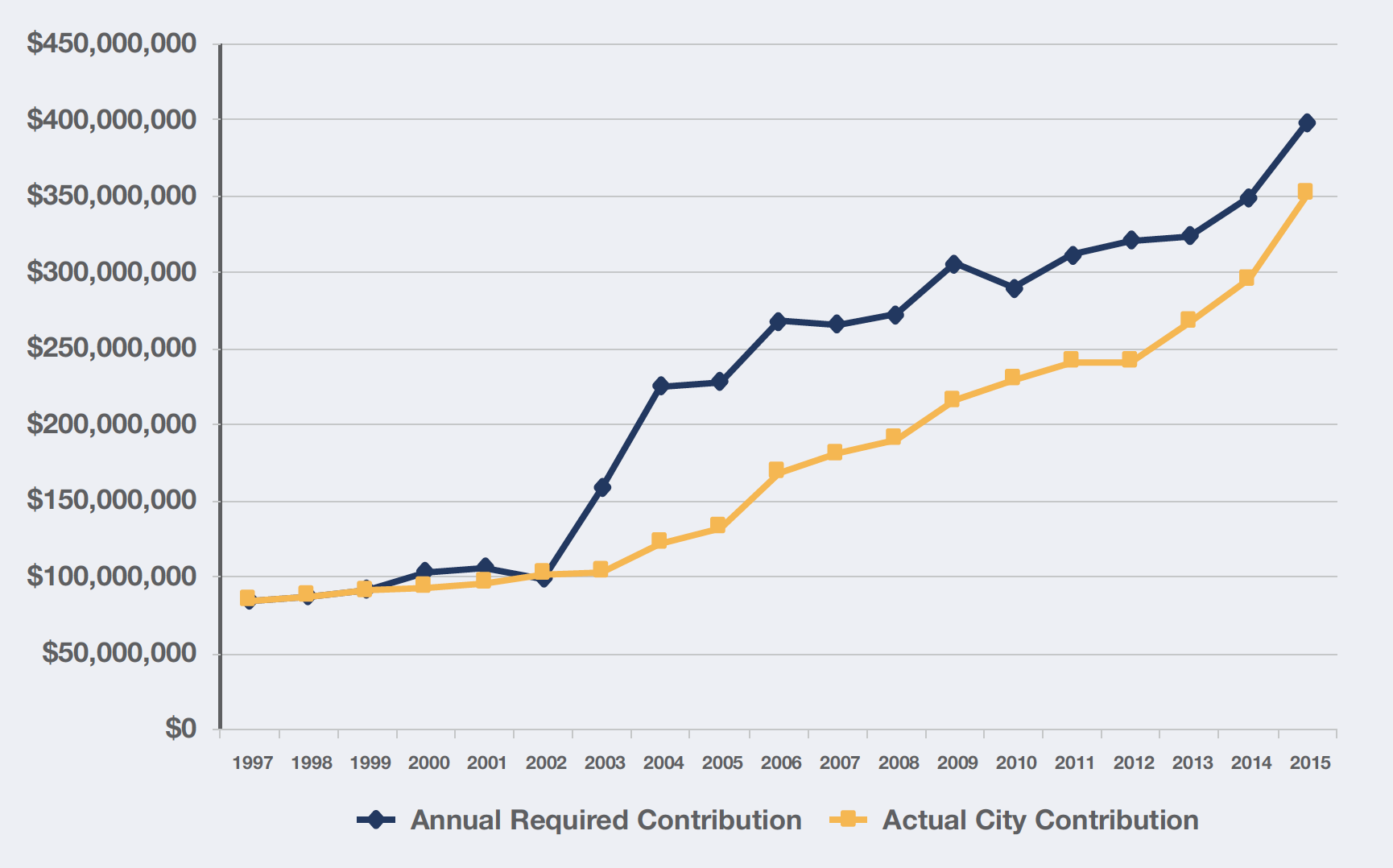

To be clear, Houston’s not alone in facing a pension challenge. Financial analysts use a measure called the Annual Required Contribution, or ARC, to determine how much money a city needs to contribute to its pension plans to keep them healthy. Houston ranks 15 among major U.S. cities, in terms of ratio of its ARC to its revenue. Simply put: Houston faces a big challenge, but it’s not a challenge that’s unique to Houston.

Still, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner didn’t mince words when he described the significance of the hurdle. “The increasing costs to the city simply cannot be sustained,” he said in his State of the City speech. “If we do not reach an agreement this year, come Fiscal Year 2018, city services will be adversely affected, hundreds of employees will be laid off and our credit rating will likely suffer.”

So how did Houston find itself in this position? It’s an important question to answer. Stakeholders must understand how the challenge was created if they want to address it. The Kinder Institute’s analysis attributes the growth in the pension systems’ unfunded liability primarily to two causes.

First: the city calculates the ARC -- the payments it must make into the retirement plans -- in such a way that even if the city paid that full amount annually, the unfunded liability would still continue to grow. The city uses a calculation to figure out how much it must contribute to keep its three pension plans financially healthy. It didn’t pay that amount in full, and even if it had, it wouldn’t have been sufficient.

The ARC agreed upon in the meet-and-confer negotiation process with two of the plans (the police plan and the municipal workers plan) is based on a methodology that backloads costs, calling for lower payments in the initial portion of a 30-year time frame and larger payments at the end. That strategy is not inherently problematic.

However, the 30-year payment schedule resets annually through what’s called a “rolling amortization schedule.” If that process continues year after year, which it does, the city would never actually reach the point at which it makes the larger payments intended to offset the previous smaller payments. In other words, even if the city makes the “full” payment, its unfunded liabilities grow.

But -- as stated earlier and shown in the chart below -- since the early 2000s, the city wasn’t even making those insufficient payments in full.

The other big factor contributing to the unfunded liability is the fact that all three of the city’s pension plans (the police plan, the municipal workers plan, and the firefighters plan) have made assumptions about the size of their investment returns that don’t align with recent experience.

When employers and employees contribute to a retirement plan, the money doesn’t just sit in a savings account. It’s invested with the idea that the returns grow over time to help fund an employee’s retirement.

Since 1992, each of the city’s three pension plans has assumed a rate of return on their investments of between 8 percent and 8.5 percent. It’s an important number. If returns fall short of that amount, then potentially, retirees won’t have the funding they were promised, and the city will have to plug the gap. If the returns are well in excess of the assumptions, then the city might have been unnecessarily putting resources towards worker retirement that could have been used for other purposes.

So what happened? Although these investment returns were exceeded in the 1990s, since the turn of the century they have fallen well short of what the plans assumed. From 2001 to 2015, the municipal workers’ plan had an annual rate of return of 6.25 percent -- well short of its expectations. This contributed $467 million to the unfunded liability. It’s a similar story for the police plan. It performed slightly better -- returns averaged 6.4 percent -- but they were so off it added $150 million to the liability.

The firefighters’ plan had the best returns -- 7.5 percent -- but that was a percentage point below what it had assumed, contributing $255 million to the underfunded liability.

Interestingly, it wasn’t just a case of bad luck for these plans. The assumptions of Houston’s pension plans are more optimistic than those of their peers. Other public pension systems have been reducing their rate of return assumptions in recent years. Nationally, the average rate of return assumption used by public pensions declined from 8 percent to 7.6 percent over the past few years. And last year, the California Public Employees Retirement System — the largest public pension fund in the nation — decided to gradually reduce its assumption from 7.5 percent to 6.5 percent over a long period of time.

Houston’s pensions are bucking the trend, maintaining optimistic assumptions about their investment returns, even as other public pensions were moving toward a more conservative approach that more closely aligned with their actual returns.

So what’s Houston to do? We explore the options for reform in another blog post. But one thing is for sure: if the stakeholders continue to assume optimistic rates of return, and use a rolling amortization schedule, it is likely that the unfunded liability will continue to grow.