"The realization that a comprehensive, multi-modal transit system will be needed in the near future has led Houstonians to take a number of preliminary steps to facilitate the development of such a system."

Quick: What year was that written? 2015? 2002? 1985

The correct answer: 1972.

This description comes from a report published by Rice University's Southwest Center for Urban Research (in some ways a precursor to the Kinder Institute) about a survey it conducted of Houstonians' attitudes towards mass transit. The center undertook the survey in 1972 in hopes of providing data that might influence the outcome of a 1973 vote to create Houston's first public mass transit agency - the Houston Area Rapid Transit Authority.

The transit proposal lost, but the problems it intended to address persisted.

Outside of minor wording adjustments to account for improvements to METRO's service, the Southwest Center's description could portray the state of the Houston region's mobility network at almost any moment over the past 50 years.

As we've written about elsewhere, because of Houston's incredible growth after 1950, the region experienced a wave of crippling congestion about every 10 years. And every 10 years, amid roiling metropolitan debates about the best path forward, residents and officials have ultimately chosen to address that congestion by expanding existing highways or building new roads.

This pattern changed slightly in recent years, especially with METRO's successes such as 2003 approval of the now-expanding light rail network and the about-to-be-unveiled reimagined bus system. Both will undoubtedly improve regional mobility. These positive outcomes have begun to shift the way Houstonians think about transit and have seemingly opened an opportunity for discussing a truly multi-modal regional system.

But, the pressure to widen and build more roadways remains. And the continued maligning of METRO and its transit proposals by many Houstonians hampers the possibility of a regionally integrated, multi-modal transportation system.

Why has the Houston region struggled for so long with this effort?

According to connections we've drawn from the 1972 survey, the results of recent Kinder Houston Area Surveys (KHAS), and a METRO-commissioned attitude survey from 2012, Houstonians' attitudes toward proposed and existing transit systems may partly explain why public transit is still a work-in-progress in Houston.

Several common themes emerged from the three surveys.

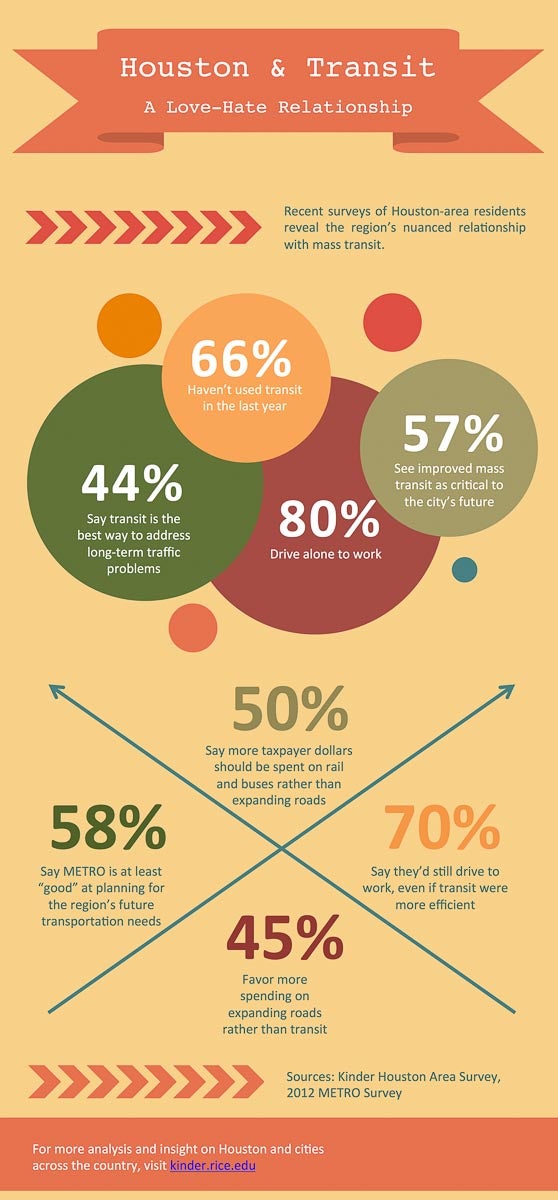

First, most Houstonians don't want to abandon their cars. Recent KHAS data found that more than 66 percent of respondents had not used transit in the year preceding the survey. In addition, more than 80 percent of respondents said that they travel alone by car to get to work.

Interestingly, 43 percent of respondents said they'd use public transportation as their primary mode of transport in the 1972 survey. But those numbers might be misleading. A great deal of anecdotal evidence suggests that many people will say they plan on riding transit at the planning stage and then never do once a system is in place. Further, while the 1972 number suggests Houstonians were more eager for and supportive of the idea of a public mass transit system, these same voters also rejected the 1973 transit plan. Perhaps they weren't as keen on the idea as the survey suggested.

The second theme that emerged from the more recent surveys is that it will take a lot of work not just to get Houstonians on transit, but also to get many on METRO, specifically. There's no way, of course, to measure how 1972 survey respondents felt about the agency (though respondents didn't have kind reviews of the private bus companies then operating.) However, KHAS and METRO survey respondents did not hide their doubts about using the transit agency's services for their main source of mobility.

When asked if they would still use their car to drive to work even if public transportation were more efficient, more than 70 percent of KHAS respondents said yes. While this obviously overlaps with the "keep-our-cars mentality," it also suggests that many Houstonians simply don't like transit or METRO's approach to providing it.

Coming at the same idea through different questions, the 2012 METRO survey found that nearly 26 percent of non-rider respondents said they either could not "imagine ever using public transportation" - a critique implicitly tied to METRO given its status as the region's major transit provider - and, more specifically, that "nothing" could motivate them to use METRO. Clearly, attitudes toward public transit are tied up with attitudes toward the agency that provides it. The agency has confronted a number of PR fights over the course of its history-from accusations of wasteful spending, to delays with new projects, and tensions between suburban and urban riders. These perceived problems affect the choice many Houstonians make to ride or not ride transit. It's not just service and convenience that get rides on board. According to its own survey, METRO has its work cut out for it to convince some riders they are a system worth using.

However, before we lapse into transit doom and gloom, two final trends we've pulled out augur a better future (or at least a better reputation) for transit in Houston.

As we already pointed out, Houstonians have been angry about congestion for a long time, but, in a reversal of earlier trends, many now see mass transit, not roadways, as the best way to deal with the problem.

In the 1972 survey, respondents rated congestion as a major problem (1.2 out of 5 on a scale of very dissatisfied to very satisfied) and saw transit as an effective way to escape the traffic (3.2 out 5). In the more recent surveys that trend has held up. More KHAS respondents (43.8 percent) selected improved public transit as the best way to address long-term traffic problems than any other option. Just 26.5 percent of residents said better or newer roads is the best way to address long-term traffic, and 27 percent said building communities where people live closer to work is the best solution.

Beyond just presenting a better option for addressing congestion, though, Houstonians now agree that mass transit should be a part of preparing the city, and its mobility network, for the future. Indeed, 57 percent of KHAS respondents now see an improved mass transit system as crucial to the future success of Houston. A key question that remains unanswered today is whether support for mass transit will translate into long-term ridership for transit.

Transit is clearly not just a way to lessen traffic congestion any longer. A small, but not statistically significant, majority of KHAS respondents (50 percent compared to 45 percent) felt that more taxpayer money should be invested in buses and rail than into expanding existing roads. This was corroborated by the KHOU/HPM Mayoral survey released last week, which showed that 41 percent of registered voters feel that mass transit is the best long-term solution to traffic. Transit again beat out bigger roads by a small margin, with 37 percent still focused on highways. And, in what the agency should take as a sign of its success, in the 2012 METRO survey 58 percent of respondents thought the agency was at least "good" at planning for the future transportation needs of the region.

So Houstonians want greater investment in transit, a responsible and forward-thinking agency to manage that investment, and a cohesive system with many transit modes to serve the region.

It feels like we've heard that somewhere before.

Let's see if Houstonians today can ensure what Houstonians called for in 1972 sticks this time around.

Kyle Shelton is a postdoctoral fellow at the Kinder Institute for Urban Research. Kiara Douds is a post-baccalaureate at the Kinder Institute. Jie Wu is the Kinder Institute's assistant director and research manager.